Next story: Talking Trees

City of Trees

by Jay Burney

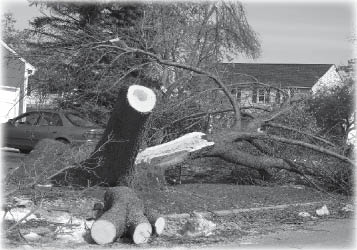

Buffalo’s urban forest has suffered tremendous damage as a result of last October’s surprise storm. How we clean up and approach a repair and restoration of this forest will characterize our community for generations to come. Will Buffalo ever again become the “City of Trees”? Here is why it should.

Our urban forest is one of this community’s most valuable assets. Mayor Byron Brown characterized our forest in the days after the storm as “our treasure, our wealth.” Certainly most people recognize the aesthetic aspect. The rolling canopies of green line our streets, parkways, pathways, parks and yards. Children climb them, they are a song house of birds and insects, and in all seasons, a carillon of the winds. A tree is both a soliloquy and a player in the symphony of nature and life. We appreciate the cool shade and comforting breezes on hot summer days. We are enveloped in the spectacular display of yellow, reds and oranges in the fall. In the winter we are in awe at the beautiful symmetry and shapes of barren branches and trunks. In the spring our senses come alive as the sap rises, the buds sprout and the trees flower with a promise of new life, a new season, hope and a new opportunity for renewal.

Many of us appreciate the fact that our urban forest is also a wildlife nursery and habitat. In all seasons we are privileged to witness and experience the critical interactions of the trees, birds, small mammals such as squirrels, and a wide variety of beneficial local insects such as native butterflies and bees. The forest truly supports these creatures, providing food, shelter and water. And the opposite is true. The wildlife is a part of the complex web of chemistry, physics and biology that keep the forest habitat and regional and global ecology healthy.

Fewer of us are aware of just how important our urban forest and its ecology is to regional and global health. Buffalo is located on the eastern end of the Great Lakes. These lakes contain nearly one fifth of the fresh surface water on the planet. The habitats and wildlife that support the cleanliness and health of that water are incredibly valuable resources. And yet few people, including planners and elected officials, understand how biodiversity works and how important our region and our forest is to worldwide ecological and economic health.

Biodiversity supports ecological health by contributing to healthy soil, air and water, helping to stabilize the climate and creating a natural balance that helps all species to remain healthy. Biodiversity is the foundation of all quality of life issues. And our area is widely recognized by scientists and conservationists as a critical global environmental resource.

For instance, the Niagara River corridor, of which Buffalo’s urban forest is a part, has been designated as a “globally significant” Important Bird Area. We share that designation with such places as the Artic National Wildlife Reserve, the Everglades and Yellowstone National Park.

The United Nations has designated portions of the nearby Niagara Escarpment, which transects the Niagara River, as a “Biosphere Preserve.” Other Biosphere Preserves include the Galapagos Islands and the Hawaiian Islands National Marine Sanctuary.

The nearby Cattaraugus Creek watershed has been identified as the largest intact ecosystem in the eastern Great Lakes.

Often when we think of preserving the environment we think of such contexts as “saving the rainforest”—unquestionably an important strategy, but we must also think about how we can save ourselves by being better stewards of our local ecology, including our critical urban forest.

Have no doubt, all of this is threatened. Threatened by urban, agricultural and industrial contamination; threatened by habitat loss; threatened by inappropriate urbanization; and threatened by inadequate stewardship of our urban forest. We can and we must do better.

Ecological benefits

Many of the direct economic and ecological benefits of the urban forest are easily understood. Tree-lined streets, parking areas and yards help moderate the stifling heat that is created by urban pavement and buildings. On any hot summer day, go to an open parking lot, say at your local grocery store, and feel the withering heat that comes from beneath your feet, draws the sweat from your body and sucks your breath away. Then go to a treed area, a park for instance. There is a significant difference. In the direct sun, radiated by the urban jungle, cars can overheat and the cost of air conditioning buildings soars. The heat can put lives at stake. Health care is expensive. Shade and greenspace helps us keep our minds and bodies intact. The urban forest is proactive healthcare.

In the winter, strategically placed trees such as evergreens can block the wind and help keep needed heat in the buildings that they protect with their insulating properties. This can keep heating costs down. To those of us that live here and pay those bills, that means a lot.

Urban forests contribute to the wealth of a city in numerous ways. Well maintained greenspaces, including parks, attract tourists and benefit businesses that are located nearby. Beyond that, property values are affected by the urban forest. Generally speaking, property and homes near and or adjacent to parks and other greenspaces are more valuable than those that are not. This means that the tax base increases.

What can be more difficult to appreciate is the complexity of the forest ecosystem. A forest, even an urban forest, provides ecological services that translate into quantifiable benefits.

An urban forest, and even a single tree, absorbs rainfall, stabilizes soil and helps control erosion. This helps to reduce the impact of flooding, which many people throughout the region experienced in basements during the October storm. This absorption of groundwater and the prevention of soil erosion prevention by trees also help to keep stormwater out of the sewerage treatment system and reduce direct contamination of our waters during storms. Treatment of contaminated water, when possible at all, is very expensive.

Buffalo has lost much of its urban forest in recent decades due to public policies reflecting both cost cuts and poor and uninformed planning decisions.

According to an American Forests-sponsored report titled “Urban Ecosystem Analysis Buffalo-Lackawanna Area Erie County, New York,” in 2003 Buffalo had a total of 3,726 acres of tree canopy cover and 6,073 acres of impervious surfaces—that is, pavement. This represents 12 percent tree canopy and 23 percent impervious surface cover over the whole city. Now we have even less tree cover. The national average for tree cover is 30 percent. We have less tree cover than most cities. That is astounding for the place once known as the City of Trees.

Even with almost twice as much hard surface as tree cover, our urban forest still provides 17.7 million cubic feet of stormwater storage during an average storm—estimated by American Forests to create an annual savings of $35.5 million. The American Forest study of Buffalo also calculates that our urban forest provides an air quality value of $825,799 annually.

That’s just the tip of the iceberg. More and more, according to climate change predictions, we can expect unusual storms. These will include more heavy precipitation events, like the October storm that from which we are still recovering, and thus more runoff issues.

There are other quantifiable economic benefits derived from individual trees and from forests. According to the US Forest Service, over a 50-year life span a tree contributes:

$31,250 worth of oxygen

$62,900 worth of air pollution control

$37,500 worth of cleaned water

$31,250 worth of soil erosion control

This suggests that the quantifiable value of an average single tree over its lifetime is well over $150,000. Multiply that by 80,000-100,000 trees and you can begin to understand the value of the urban forest.

Strategies for recovery

As we address the long-term consequences of what was arguably the greatest natural catastrophe in the history of our city, there are a number of things that we need to consider. Plans need to be created and decisions should be made that are public and accountable. There are various estimates that about 90 percent of our urban forest has been damaged by the storm and, of that, about 40 percent is lost. What can we do? Simply put, we must replant and restore.

Much of the current discussion centers on the hiring of an arborist or several arborists to manage this discussion and manage a restoration and replanting plan.

No question we need arborists. We need arborists to care for injured trees and to help us clean up. But this step alone may not provide adequate solutions or restoration strategies that are as cost-effective and as ecologically important as they can be. Hiring an arborist is just a starting point.

Understanding what an arborist is, what an arborist does, is fundamental.Arborists are essentially defined as tree surgeons. An arborist’s expertise is fundamentally about the health of an individual tree—not the health of a forest, and certainly not the health of an entire ecosystem.

A certified arborist—certified, for instance, by the International Society of Arborists—is trained essentially in the knowledge and skills of pruning, trimming and an approach to disease identification and treatment that is both complicated and, from the perspective of an ecologist, insufficient.

For instance, most certified arborists are trained in the use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers in order to treat disease and insect activities that sometimes, but not always, are harmful. In the past, in Buffalo, this has led to problems, including the remarkable pesticide and economic debacle that visited Buffalo in the mid 1990s as a result of efforts to control the elm leaf beetle. The prescribed treatments that were sold to the city were not cost-effective and created health and aesthetic issues that were widely reported at the time. On a positive note, the environmental and economic calamity for the city was corrected by an aggressive, citizen-based movement that refocused indiscriminate pesticide applications that for instance, harmed beneficial insect populations, toward a more reasonable, least-toxic or nontoxic strategy. This included the creation of a City of Buffalo Pesticide Management Board—a body that should be a part of the reforestation discussion. A least-toxic strategy is now recognized by some arborist certification bodies, but a commitment to such a strategy has to be spelled out in any agreement that involves the hiring arborists for Buffalo, especially any that are overseeing a larger program that involves habitat and ecology.

Generally speaking, and there are exceptions, an arborist is trained in the planting and identification of horticultural species and varieties of trees including ornamental and what the industry calls “disease resistant” and “urban durable species.”

For instance, the City of Buffalo now has an arborist-influenced “City of Buffalo Approved Tree” list. This approved tree list, passed as a law by the Buffalo Common Council, neglects an understanding of ecology and all but makes the planting of native trees illegal. While it can be argued that any tree is better than no tree, native trees and shrubs are pretty important in the support of native biodiversity. Many species are very specific to the kinds of plants and trees that they require in order to survive. A commitment to native trees and shrubs should be a part of our urban forest mission statement, but this habitat-centric knowledge is not part of our current discussion. In the overall context of an urban forest, certified arborists generally do not have adequate training about ecosystems, impact and support of native habitats, the beneficial value of biodiversity and the specific biodiversity of our region.

It is important to understand whom we are hiring to do the recovery work. The FEMA response to the October storm was both beneficial and a disaster in its own right. We needed help, and we didn’t have time to organize and supervise the initial implementation adequately. (I hope that the mayor has learned a lesson about disaster preparedness because chances are there are more to come.) The result was a relatively quick cleanup of most streets in the city, but the contractors who did the work—called “hurricane chasers” early on by Mayor Brown, because they contract to follow disasters and leave town with pockets full of loot—in many instances nearly clear-cut streets, parks and neighborhoods. They don’t have to live with their work, but we do.

Mayor Brown stated early on in the wake of the October disaster that every tree that was coming down in this city would be “designated as ‘not savable’ by an arborist.” My neighborhood was inundated with tree crews and they clear-cut several blocks of lovely and beautiful mature trees—most, in my opinion, that did not need to be cut down. I approached several of the crews with questions. I asked one fellow who seemed to be at least tacitly in charge, “Who is the arborist?” He looked at me, briefly flashing anger, and said, pointing to the 15 or so chainsaw-wielding folks engaged in cutting trees up and down my block, “Everyone out there with a chainsaw is an arborist.”

A blue ribbon panel of stakeholders

And so we move on. It is important to take an ecological and a scientific approach to reforesting Buffalo. We should endeavor to understand the quantifiable value of an ecosystem approach and the potential impact on the habitats and biodiversity for which our area is so noted.

The mayor needs to appoint someone or several someones to do this. Perhaps a blue ribbon panel. This panel should organize an approach that links all efforts, enlisting public participation as well as the City of Buffalo Environment Management Commission, the Pesticide Management Board and conservation and environmental groups from throughout the region. The Olmsted Parks Conservancy needs to be included. The Common Council and the Planning Board need to be included. This needs to be a big and broad effort. The plan will need to be addressed by the State Environmental Quality Review Act, so that it is subject to public scrutiny and accountability. We do not need our city’s reforesting plans made behind closed doors, at the behest of, for instance, the City of Buffalo Fiscal Stability Authority. The mayor has already clearly stated that any and all economic decisions related to reforestation budgets will be made by this control board. This is not acceptable because the city needs to be accountable for the plan it adopts. The control board cannot be held accountable.

One thing is for sure. How we deal with the continuing cleanup and restoration of our urban forest will help to characterize our community—and our ecological, economic and social health—for generations. It will take efforts from every one of us to make sure that we come out of this with a chance once again someday to be a healthy and productive City of Trees.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n2: Return to the City of Trees (1/11/07) > City of Trees This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue