Film Alive

by M. Faust

Dream palaces,” they used to call movie theaters, back in the day when someplace like the Shea’s Buffalo was only moderately more ornate than your typical theater. The phrase went out of usage in the 1960s, when cookie-cutter multiplexes started becoming the norm. But the phrase is still apt, especially when you compare the experience of seeing a movie in a theater with that of watching it at home or on a handheld device like an iPod.

As critic David Denby writes in the current issue of The New Yorker, “In a theatre, you submit to a screen; you want to be mastered by it, not struggle to get cozy with it…The movie theatre is a public space that encourages private pleasures: as we watch, everything we are—our senses, our past, our unconscious—reaches out to the screen. The experience is the opposite of escape; it is more like absolute engagement.”

Denby’s article (it’s titled “Big Pictures,” and you can read it online at www.newyorker.com) argues at length that no matter how much digital technology improves, no matter how grand and costly and big your home theater components, nothing will ever substitute for experiencing a movie in a theater.

Using the examples of Taxi Driver and Brokeback Mountain, which he watched on state-of-the-art home theater systems, Denby muses what it is that compels us as we sit, still and quiet, before a larger-than-life screen. When a film works, we become more than observers—we are participants in the emotions of the characters. “The grandeur of the terrain [in Brokeback Mountain],” he writes, “is not something the men are necessarily conscious of, but the massiveness of the mountain range, the startling clarity of the air, the violence of the weather enlarge the experience of feelings they have no words for and can’t control. If you watch the movie on a small screen, you’re not living within this great breathing, palpable place. The small screen takes the emotion out of the landscape.

“If watching movies at home becomes not just an auxiliary to theatregoing but a replacement of it, a visual art form will decline, and become something else. Kids who get hooked on watching movies on a portable handheld device will be settling for a lesser experience, even if they don’t yet know it—even if they never know it.”

Older viewers (which to Hollywood is all of us over the age of 25) counter that they no longer go to movie theaters because the experience so seldom lives up to expectations: Rude audiences, indifferent presentation, excessive advertising, oversized and overpriced concession items are a high price to pay for Hollywood product manufactured primarily for 12-to-25-year-old viewers. All true, all lamentable—and all the more reason to support moviegoing opportunities that live up to the needs of the art.

To the extent that the young students who form the core audiences of the Buffalo Film Seminars did not already have this experience of theater viewing, they owe a huge debt to Bruce Jackson and Diane Christian, who began the series in fall of 2000. Students in most universities aren’t so blessed: They have to watch their assignments on videotape or DVD, as colleges lack even the 16-millimeter capabilities that used to be standard.

But the Buffalo Film Seminars serves more than just the 45 students who are allowed into the class each semester. The theater at the Market Arcade Film and Arts Center where screenings for the seminar are held—the largest house in the complex—holds 324 people, and I’ve never seen it less than 75 percent filled. That makes for at least a few hundred people who show up downtown every Tuesday night to see films as they were meant to be seen—as they may have never seen them before and may never be able to again.

The semester that begins this Tuesday, January 16, with the Buster Keaton comedy The General, is a kind of “best of” series. Viewers were asked to vote for the film they would most like to see again from previous years of the Buffalo Film Seminars. The result may be lacking in surprises, but week by week it offers the chance see to 15 undisputed masterpieces of world cinema.

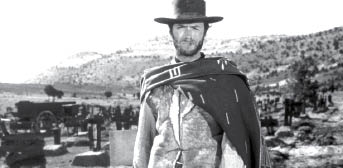

And no matter how well you may know these movies, no matter how often you may have watched them on DVD, there are at least a few that you simply have not really seen if you haven’t seen them in theater. David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, for instance, with its unforgettable shot of Peter O’Toole emerging in the far distance from an infinite expanse of desert; or Sergio Leone’s underappreciated The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, with what for my money is the most memorable climax in all of film history.

Other films demonstrate that epic size isn’t the only advantage of public viewing. Japanese master Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story develops an almost unbearable range of understated emotion when seen properly, as does Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thieves, set in the still ravaged street of post-war Rome. Then again, size brings out the detail of the beautiful black-and-white cinematography of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil and Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. (When Paul Simon sang “Everything looks worse in black and white,” one can only hope he was kidding.) And in the late Robert Altman’s Nashville, there is simply so much life bursting from the screen that you’ll want a chance to watch all 160 minutes of it again.

God willing, you’ll have one. But don’t count on it.

The complete schedule for the new semester of the Buffalo Film Seminar is as follows. All films are shown at 7pm on Tuesdays at the Market Arcade Film and Arts Center, 639 Main Street. Films are open to the general public, and viewers are encouraged to stay for the audience discussion that follows each film:

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n2: Return to the City of Trees (1/11/07) > Film Alive This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue