Frame by Frame

by Gerald Mead

A pair of exhibitions currently on view at the Castellani Art Museum of Niagara University exemplify two distinct strengths of this (in my opinion) undervisited institution—their well respected Folk Arts Program, now in its 15th year, and their exceptional TopSpin series, inaugurated five years ago by soon-to-be departing director Laurene Buckley. Both of the programs demonstrate the museum’s serious attempt to focus on both highly regarded and emerging artists from our area and bring into focus the region’s unique cultural heritage. The long-term exhibitions that comprise the TopSpin series are also accompanied by full-color brochures that include interpretation of the artwork—a valued asset to the artists who are featured.

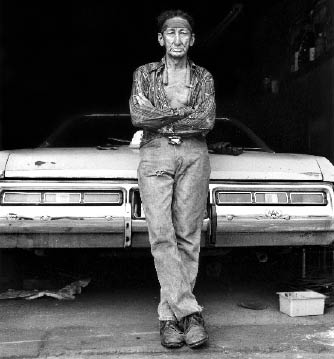

Milton Rogovin’s internationally renowned documentary photography is by now well known in this area, and his sensitive portraits of ethnic communities, steel workers, miners and other groups have been presented in a multitude of solo exhibitions in the US and abroad. (My own familiarity with his work extends to 1993 when I organized a traveling exhibition of his Lower West Side Revisited Series.) Having said that, it can be a challenge to accomplish something fresh with the work. The Castellani has risen to the challenge and with Milton Rogovin: Native American Series: 1963-2002, Rogovin’s work has entered the next phase of its exhibition life, one in which his work is contextualized and used as a resource to examine the cultural heritage that he captured with his lens over the course of many decades.

In a sense it is ironic that at the age of 97 years, Milton is able to witness this process of recovery that his images of individuals that he long referred to as “the forgotten ones” are enabling. Considering that the Native American series had never been shown as a group and the fact that the Castellani is a stone’s throw away from the Tuscarora (one of the six Iroquois Nations) Reservation—original site of some of the images—this is the right place and the right time. To accomplish this and ensure that the Native American perspective was respected in the process, Curator of Folk Arts Kate Koperski assembled a curatorial team consisting of Allan Jamieson (Neto Hatinakwe Onkwehowe), Dr. Cynthia Conides (Buffalo & Erie County Historical Society) and the artist’s son Mark, who currently coordinates Rogovin’s photography.

So how does this all play out? This multifaceted “visual analysis” approach allows his work to be examined in a cultural and sociopolitical as well as an aesthetic framework. The images are organized into thematic categories including Traditions, Urban Indians, Reservations and Political Activism. For those familiar primarily with his portraits, it may come as a surprise to see stunning examples of his take on still life and rural and urban landscapes. The fortuitous availability of Rogovin’s contact sheets (they have been archived at the Library of Congress since 1999) prompted the inclusion of several enlarged contact sheets to show the images from which Milton selected his final images. Seeing the “rest of the story” in the form of other views taken at the same time is fascinating and gives the viewer unique insight into the photographic editing process. The oral history component—research by Buffalo State College museum studies students under the direction of Dr. Conides—actually predates planning for this exhibition. It was bolstered in the months leading up to the exhibition by the discovery of a splint ash basket that was made by the late Lena Hudson Johnson, a member of the Seneca Nation who was the subject of one of Rogovin’s most emblematic images from this series. The display of that basket with the image of its maker is a simple yet powerfully merging of artifact and image. It is gestures such as this that enhance and deepen the meaning of Rogovin’s work. The interactive component of this exhibition—collecting information about the individuals and locations depicted—has also been very successful as visitors have provided information that will become part of the extended labels for the work as the exhibition travels.

Finally, a contemporary Native American voice is provided by local Iroquois author and educator Eric Gansworth, who was commissioned to write four poems in response to Rogovin’s images. His expressive texts—displayed alongside the works the reference—more that adequately achieve his aim to complement rather that interfere with the inherent eloquence that he observed in the pictures. Rogovin’s images, which over time have morphed from contemporary documents to historical representations of community culture, do not lose their power amidst these elements of contexualization. In the face of it all, they continue to be visually stunning and intellectually engaging.

A few steps away in the next gallery, you enter the enigmatically titled exhibition Robert Lynch: Drink Orange Juice and Hang out with the Horses, and are walloped (in a good way) with a few dozen of Lynch’s surreal and quixotic paintings, each rendered on individual two-foot-square panels. Curator Michael Beam’s installation of the work, done in part to echo the film-frame-like format of the paintings, transforms the walls of the gallery into one giant sliding puzzle (remember those small games where you slid the plastic squares to form a picture?). It’s a welcome relief from the usual “line ’em up” museum strategy and highly appropriate for this series of Lynch’s work, serving as a nod to the playful side of the paintings. At a mere 34 years old, Lynch is one of those “young emerging artists” you hear so much about, but in fact for many years he has balanced his artistic practice with a celebrated musical career as a multi-instrumentalist, singer/songwriter/producer and art educator. (Obscure but interesting fact: A decade ago he won first prize in the Late Night with Conan O’Brien College Music Search.) More than once he’s been described as a “renaissance man,” and the diverse spheres that his paintings reference—from politics to cartoons and seemingly every stop in between—support the fact that his appetite for visual stimuli is bursting at the seams. His is an imagination that knows no visual bounds and in fact resists the implications that boundaries need to be drawn at all. His artist statement tells us that he likes the ridiculous, the bittersweet and the ambiguous—it’s all there in the work and more.

In true 21st century fashion, Lynch turns to the Internet (as well as his trove of resource files and copious notes to himself) for inspiration and revels in the fact that a single Google image search can eventually yield a stream of arbitrary and unrelated images. This flood of images is edited, distilled and combined in ways that appeal to Lynch’s love of randomness and serendipity. It is the odd and inexplicable connections that he makes that draw you into the work. The song-lyric-like titles may provide a clue now and again—but most of the time they are equally enigmatic. You get the sense looking at the work that they are replete with inside jokes and the challenge is to recognize them—or not—and Lynch is fine with that as he encourages viewers to “chuckle and stare quietly” at the works. The floating heads, birds and trees are rendered in a confident hand characterized at times by broad expressive brushwork. He freely experiments with media such as acrylic, ink, marker and pencil to suit his needs and the result is a richly textured surface of varying marks that reinforce the disparate nature of the images. The occasional appearance of lines of text in that quirky 1960s font combined with square format of the works even remind you (and the artist) of album covers.

Tying the works in the series together is Lynch’s healthy command of composition in each of the paintings and the use of a number of surrealistic devices, such as the taut strings linking objects and a distant flat horizon line. In another alteration of the norm, however, each of Lynch’s horizon lines are marred by single anomalous “dug hole” like notch. If you dig deep enough (okay, actually ask the artist) you may begin to crack some of the codes. It turns out that the appearance of boxing gloves in some of the works is a veiled reference to Lynch’s emotional museum encounter with George Bellow’s astounding oil painting of boxers titled Stag at Sharkey’s. But then again, he admits, the shape of the boxing gloves can just as easily be interpreted as balloons with an altogether different stream of metaphors. And so his process of combination and improvisation merrily moves along and we are fortunate to go along with it and enjoy the ride.

These two exhibitions, not to mention works by Bierstadt, Dali, Lichtenstein and Rauschenberg in permanent collection exhibitions in the other galleries, are more than ample reasons to make the short trek across the Grand Island bridges and into Niagara County to visit the museum—it’s really not as far as you think and you don’t need your passport.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n24: Stumped (6/14/07) > Art > Frame by Frame This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue