Scene & Unseen

by Thomas Dooney

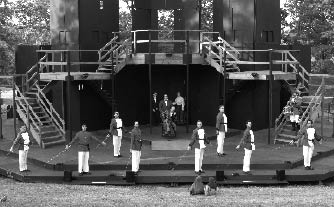

This summer, you and about 40,000 others can enjoy All’s Well That End’s Well (not seen here since 1987), and Othello (last in the park in 1990) presented by the good folks of Shakespeare in Delaware Park.

If the oral history of Shakespeare in Delaware Park could be encyclopedically chaptered, the biggest section would be under “U,” for unforeseen, undone and unusual events. That would include unexpected replacement of performers, unidentified insects swallowed while acting and, despite the best efforts, goals unaccomplished…so far.

In tribute to that legacy, here gives an accounting of some things you won’t see at Shakespeare in Delaware Park this summer:

Invisible electricity

The Shakespeare in Delaware Park production of All’s Well That End’s Well is set in a mannered, controlled Edwardian era. What you will not see so much is the technological controls that make this romantic comedy possible. Newly refurbished, underground conduits connect the stage at the bottom of the hill and the call booth at the top of the hill. This reduces the 21st-century wiring from obstructing the stage doings of a previous era.

Lisa Ludwig, managing director of the festival, reports this task was accomplished just in time and by the donated services of Ferguson Electric, one of the region’s oldest and most respected electrical contracting firms.

Lighting control board

Another electrifying drama recently was played out with the arrival of a new lighting control board. By the time the board was tested in the park, it was found to not work, due either to a problem in transport or manufacture. A series of urgent phone calls ensued.

Start the suspense clock now.

The vendor in Wisconsin promised a replacement unit, direct from the factory. Swell, when? Another series of phone calls between Wisconsin and Japan. Bad news: Not soon. Good news: A loaner from a local theater is arranged. Better news: A replacement unit is found and is being flown in. Bad news: The plane breaks down.

Good news: It’s here.

A sad tale, best for winter

The public immediately embraced Shakespeare in Delaware Park in 1976, when Saul Elkin, then chair of University of Buffalo’s Department of Theater & Dance, announced it as an off-campus program for visitors to the park. It was Elkin’s hope that UB curriculum would offer training for the performance and production of Shakespeare’s plays. Actors would be educated in verse, movement and combat; designers would learn the difference between a doublet and a farthingale; and we would all be better off for it.

Academic changes can move at a glacial pace and UB withdrew its support from Shakespeare in Delaware Park before a training program could be installed. A stinging irony is that the severance letter from the dean’s office was prefaced by a quote from The Winter’s Tale.

While a SUNY-based Shakespeare conservatory has never come about, Shakespeare in Delaware Park is now a target destination for students from all the area’s important theater programs. Shakespeare’s plays appear on the production calendar for Buffalo State, Niagara University and Canisius College at least once in a theater student’s four years on campus. The stage in Delaware Park is where trained actors from all these schools first work together at the start of their professional careers.

Two Noble Kinsmen, etc.

Without getting into folio count, possible collaborations and the speculative legacy of “real” authors from Christopher Marlowe to Queen Elizabeth I, Shakespeare in Delaware Park has produced 26 of the plays attributed to Shakespeare. However, there are 12 Shakespeare scripts not yet performed in Delaware Park.

“Well,” says Elkin, “it was never our goal to do all Shakespeare’s plays.” True that, but it is badge of honor amongst Shakespearean aficionados to have seen all the bard’s scripts in performance; amongst actors, to have performed in all—and there are only a handful worldwide.

“We do have a pretty good record,” says Elkin. “We have done most of the comedies. We are also pretty good on the histories and tragedies.” Elkin admits that titles are chosen for their familiarity and he has made some conservative choices in order to attract audiences back to Delaware Park. He concedes that, after 32 years, the regular, repeating audiences would likely gamble on seeing a free production of The Two Noble Kinsmen, Henry VIII or Coriolanus.

If there is one show he regrets not producing, it is Antony and Cleopatra. Elkin hoped to star Lorna C. Hill as the Egyptian queen, who time has not tempered or tamed. Exciting as that prospect might have been, Hill demurred from this coveted role, citing allergies that would keep her from performing out of doors, surrounded by nature in all its pollenous, insected glory.

A wooden “o”

Although a house is not what makes a home, one cannot help but wish for a little bit of architecture in Delaware Park to better accommodate artists and audiences. Since the 1970s there has been talk about construction of a theater, or at least theater fittings, to ease the annual setup. Before knees jerk, it is important to remember that a city park may look as lovely as wilderness but is actually as artificial as Disneyland.

The parks of Frederick Law Olmsted and his partner Calvert Vaux are planned, landscaped, deliberately planted environments with manufactured crests and rills, complete with engineered ponds and streams. Creators of our Delaware Park and Manhattan’s Central Park, Olmsted and Vaux advocated urban parks should not be “tree museums” but places that evolve to meet the needs of the citizens. For example, during its first 70 years, Central Park’s Sheep Meadow was home to an actual flock of sheep. The livestock were removed during the Great Depression because the poor squatters were killing and eating what they could catch.

Vaux, the better half of the collaboration according to Francis R. Kowsky, professor of art history at Buffalo State College in his 1998 book Country, Park & City, encouraged structures in parks and personally supervised the construction of Belvedere Castle in Central Park. A hundred years later, in the 1960s, Central Park Conservancy allowed for the construction a grandstand and permanent stage as summer home for the New York Shakespeare Festival.

Eternal summer shall not fade

Also unseen, intangible really, is that over the course of 32 summers, Shakespeare in Delaware Park has upped the region’s cultural literacy. The renegade Brazen-Faced Varlets succeed in part with their lesbianic pentameter spoofs (Ramona and Juliet last summer, Midsummer Dyke’s Dream this) because a generation of Buffalonians are familiar with references, general to obscure, in these shows.

I know children under 10 who know who Puck is, understand revenge as a motive, know “thee” from “thy” and grasp convoluted plot twists because of a single evening in the park.

Not that they are satisfied with only one evening in the park.

And neither should you be.

All’s Well That Ends Well, directed by Derek Campbell, starts performances this week and continues through July 16, Tuesdays through Sundays (weather permitting) at 7:30pm on Shakespeare Hill, behind the rose garden in Delaware Park.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n25: Mark Freeland, May 1, 1957-June 14, 2007 (6/21/07) > Scene & Unseen This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue