Next story: News of the Weird

No Deal on the Buffalo Casino

by Bruce Jackson

The federal case

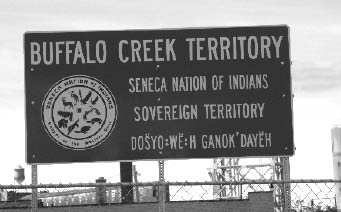

The bottom line on US District Court Judge William M. Skretny’s 51-page January 12 decision in the Buffalo casino case is this: The nine-acre parcel of land in downtown Buffalo on which the Seneca Nation of Indians wants to build a casino never received the kind of examination from the federal government that would determine whether or not it was in the category of Indian land on which gambling could occur. Absent an adequate determination, no casino gambling can occur in Buffalo.

There was no question, Judge Skretny said, that the Senecas owned the downtown land. But there is a huge difference between land Indians own and land that meets the legal requirements for casino gambling. The Senecas can build anything they like on their downtown Buffalo property—hotel, school, hospital, sphinx, casino, anything at all. But they cannot gamble on that land or invite anyone else to gamble on it. If they build a casino in spite of Judge Skretny’s decision, as some of their spokesmen have said is their plan, they risk pouring money into an enterprise even more pointless than the slot machines their clients so dearly love. But unlike most of their customers, they’ve got lots of money and perhaps can afford to squander it in a pointless public gesture.

Judge Skretny reversed and remanded the National Indian Gaming Commission’s (NIGC) 2002 determination that it was “Indian Land” (which is specifically defined by federal law) and therefore gambling-eligible land as “arbitrary and capricious.” He sent the determination back to the NIGC, saying this time they had to give it a serious rather than a cursory look, which means this time the commission will have to say what parts, if any, of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 (IGRA), which controls all gambling in Indian land, applies to the Senecas’ downtown Buffalo purchase.

That act prohibits, with very few exceptions, gambling on Indian land acquired after October 18, 1988. If the NIGC decides the land is in fact Indian land, and if that land falls under one of the few exceptions, gambling will be allowed—at which point casino opponents will be back in court challenging that determination. If the NIGC decides the Seneca purchase is not Indian land, the Senecas will in all likelihood be in court challenging that rejection of their request.

Until the commission determines whether or not the Senecas’ ownership of the land is included or is excluded by the restrictive section of the IGRA, the parcel is just land that the Seneca Nation owns, nothing more.

The plaintiffs in the lawsuit were Citizens Against Casino Gambling in Erie County and a number of other groups and individuals. After the suit was filed, Erie County Executive Joel Giambra asked the judge to permit himself and the county to join the suit. The judge agreed.

The defendants were all federal officials and agencies: the Secretary of the Interior, the Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs, the chairman of the NIGC and the NIGC itself. Any or all of them could appeal Judge Skretny’s ruling and thereby attempt to block any reconsideration by the NIGC. Most lawyers I’ve talked to think there is little likelihood that the Second Circuit Court of Appeals will reject a judge’s decision that a federal agency clarify a poorly done determination.

The Seneca Nation of Indians was not a party to the lawsuit but asked the judge if it could submit an amicus brief. Amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs are documents submitted by individuals or organizations who either have information that the judge might use in his determination or who have interests not represented by the plaintiffs or defendants. Since these briefs become part of the record and take time to deal with, judges are parsimonious about accepting them. Judge Skretny agreed to accept the Seneca amicus brief, but he rejected all of its major points, the most important of which was a request that he dismiss the entire lawsuit. No one, he said, was challenging the Senecas’ ownership of the land; the only questions had to do with the uses to which it was being put and those interests were well enough represented by the actual defendants.

He dismissed as moot most of the plaintiffs’ major requests, which casino proponents have been crowing over in interviews this past week. They’re crowing over nothing. “Moot” means simply that a question has, at this point, no practical significance; it doesn’t mean the question is in any way defective. Judge Skretny said that proper determination of the land parcel’s legal status had precedent over all other arguments, so they had to wait for that determination. Since the judge did not dismiss those major requests on their merits, they can all be brought up again should the NIGC rule that the Buffalo Creek nine acres is Indian land eligible for gambling.

The full 51-page decision is online at http://buffaloreport.com/2007/judge.skretny.order.011206.pdf.

Running mouths

For several months now Buffalo lawyer Michael Powers has been insisting at great length and with no perceivable doubt that the proposed gambling joint in downtown Buffalo was a done deal. The only options—Powers confidently told the Common Council, the citizens at the council’s public hearing on the casino, the city’s control board, the Buffalo-Niagara Partnership and who knows who all else—were to go with the flow or to get rolled over by the inevitable.

No one on any of the public bodies before which he performed his “done deal” routine ever made him defend his assertions. No one on the control board or the council or the partnership said, “What’s your evidence for saying this is a done deal?” They just listened to him as if he were presenting a report rather than hyping a position.

Sometimes Powers was paid for his efforts by Buffalo developer Carl Paladino, sometimes by Mayor Byron Brown’s office, and sometimes, he claimed, he was doing it pro bono for the welfare of the city he lived in a suburb of, a claim his quondam employer Paladino disputed.

It was difficult to tell if Powers was working as a lawyer or if he was working as a flack for any of the aforementioned or for clients still unnamed. In any case, he stayed on message: The casino is a done deal, a done deal, a done deal.

Wrong. Judge Skretny’s decision says all bets are off. There isn’t any deal, done or otherwise. There isn’t anything, at least not until the NIGC comes up with a reasoned and documented decision on the status of the Buffalo property, and that decision, in turn, stands up to the court challenges that surely will come.

Powers isn’t the only one who let his mouth get in front of the facts in this case. An hour or so after the decision came down last Friday, Erie County Executive Joel Giambra called a press conference in which he announced that the Buffalo casino was dead. That’s no more a certain fact than Powers’ claim that the casino was a done deal.

As is often the case in major public issues, a lot of people on either side run their mouths, but the only voice that really counts is a judge who looks at the facts and at the law and who then says whether what is going on is legal or illegal, whether it can continue or whether it must stop. That is what happened six years ago when New York Supreme Court Judge Eugene Fahey told the Buffalo and Fort Erie Public Bridge Authority that it had to stop whatever expansion it was doing and come into compliance with New York’s environmental law. And that is what happened last week when US District Court Judge William M. Skretny told all the talkers and players in the proposed Buffalo casino that they’d have to stop what they were doing until there was a legitimate determination of whether or not that casino would meet the conditions for gambling set forth under federal law.

The land in question

This case hinges primarily on the interpretation and application of two laws, the 1988 IGRA and the Seneca Nation Settlement Act of 1990 (SNSA).

IGRA sets up the conditions under which casinos can be operated on Indian land and a mechanism for monitoring their operation. It creates a commission—the NIGC—to oversee and regulate all gambling on Indian land and to consider applications for new casinos. With only a few exceptions casinos can only go on land Indians owned before the adoption of IGRA in 1988.

One of those exceptions has to do with land acquired in a land claim process. In her November 12, 2002 letter allowing the Buffalo project to go forward, Secretary of the Interior Gale Norton said the Buffalo property was the result of a land claim process because a small portion of the money used to buy the Buffalo property came from the $30 million provided by the Seneca Nation Settlement Act.

Former Congressman John LaFalce, who coauthored the SNSA with Amo Houghton, disputes that. He says using SNSA to help legitimize setting up a gambling joint 14 miles from any reservation in a location where it would otherwise be prohibited by the state constitution is a perversion of the act’s intention and substance. Neither he nor Houghton, nor the members of Congress who unanimously voted for it, ever contemplated it would be used as a gimmick to get around state law. More important, he says, SNSA isn’t a land claim act anyway, so it and money derived from it have no place in an IGRA action. The Seneca Nation of Indians, he says, owned the land around Salamanca before the SNSA and they owned it after the SNSA. The act didn’t compensate them for land taken from them improperly; it compensated them for having been underpaid by the non-Indian lessees who had been living there. The SNSA was, in Judge Skretny’s words, Congress seeking “to assist in resolving the past inequities to the SNI, to provide stability and security to the non-Indian lessees, to promote economic growth and community development for both the SNI and the non-Indian communities established on reservation land, and to avoid the potential legal liability on the part of the United States that could result if a settlement was not reached.” No land ever changed hands or status as a result of SNSA.

The judge has told the NIGC to sort this out and document how they did the sorting. The commission has three members, two of whom must be Indians. The chair is selected by the president, the other two by the Secretary of the Interior. Most of NIGC’s work has to do with keeping the casinos honest. As the number of attempts to create off-reservation casinos has increased, the commission has taken on a gatekeeper function as well. Since NIGC can only regulate gambling operations on lands taken into trust by the federal government that was either Indian country before 1988 (which the Buffalo parcel was not) or fits through one of the loopholes in § 2719 of IGRA, that gatekeeper function is critical. If they say a parcel of land does not fit through a loophole, then Indian gambling cannot occur on it.

A television reporter at Giambra’s press conference asked, “Since there are two Indians on the Commission won’t they just rubber stamp this?” The answer is no, they won’t just rubber stamp this. That’s what the chair of NIGC did last time and that is why Judge Skretny said he was kicking it back to them. This time, the judge said, they had to give reasons in law for their decision.

So won’t those two Indians find excuses in law to do what they want to do anyway?

That maligns the commissioners and it ignores NIGC’s behavior. It has, in several recent cases, some of them similar in key regards to this one, rejected tribal claims that acquired land was gambling land. They are willing to say no. They post their final determinations in the Reading Room/Indian Land Opinions section of the commission’s Web site: http://www.nigc.gov/ReadingRoom/IndianLandOpinions/tabid/120/Default.aspx. See, for example, the July 19, 2004, Wyandotte Nation and the September 1, 2006, Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians restored land rejections. This is not a gimme for the Senecas.

That Web page also contains a link to former-Secretary of the Interior Gale Norton’s November 12, 2002, letter explaining why she did not affirmatively approve the Seneca Nation of Indians’ request but let the permitting go forward by non-action instead. She had, she said, major problems with many key issues in the Buffalo deal, but finally didn’t want to get between the governor and the tribe. Judge Skretny’s decision telling the NIGC to give this a serious, reasoned look doesn’t reverse her letter; rather it abolishes it. The NIGC now has to do the job that Norton sidestepped and the NIGC chair glossed over three years ago.

This gatekeeper function wasn’t envisioned for NIGC when IGRA was written, so there doesn’t seem to be a set of rules and regulations setting forth how these determinations are made. There’s no formal procedure by which interested parties can make their concerns known, no equivalent of the amicus brief in a court case, no notice or hearing requirements in the regulations and the way appeals of NIGC decisions are handled. They seem to be handled on an ad hoc basis.

So we know who gets to make the next decision—the National Indian Gaming Commission—but not how that decision will be made or when it will be made. “Significantly,” a lawyer told me, “the regulations provide for appeal only of a disapproval of a gambling ordinance, and the appeal can be made only by the Indian nation—though if the Indian nation does appeal a disapproval, third parties are permitted ‘limited participation,’ i.e., a written submission either for or against the disapproval.”

The state of the suit

Nothing’s over. The Buffalo Creek casino is stopped for now, but there are many stations ahead on the road to final resolution of this mess.

If NIGC says the Buffalo Creek property is not Indian land, then the Seneca Nation of Indians will probably go to court to challenge that decision, and the roles in the case just adjudicated in Judge Skretny’s court will be reversed: The plaintiffs whose case has been underwritten by Citizens for Better Buffalo will perhaps ask to file an amicus brief supporting the decision of the NIGC, while the Seneca Nation of Indians will be challenging the government’s decision.

If NIGC says the Buffalo Creek property is Indian land, it will have to do so with specific reference to the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988, something no federal official or agency has thus far done. That will provide the specific grounds for the plaintiffs to return to Judge Skretny’s court, bringing along all of the points that were mooted out this time.

It might be that the environmental impact study, which former Buffalo Mayor Anthony Masiello, current mayor Byron Brown and former governor George Pataki worked so hard to avoid is, because of Judge Skretny’s involvement, now inevitable, and for the first time public officials will have to take seriously the huge economic harm the casino would do to the city.

Such studies are routinely done elsewhere; Buffalo is an anomaly. Nearly all the pending casino applications listed on the Indianz.com Web site (http://www.indianz.com/maps/casinostalker) have done environmental impact studies or are doing them now. The Bad River and St. Croix bands of the Chippewa Tribe have worked since 2000 on putting an off-reservation casino into Beloit, Wisconsin. First, Beloit had a referendum in which 61 percent of the voters approved the idea of a casino. Then there was an environmental assessment in 2003 and a draft environmental impact statement in 2005. The process is still going on.

What happened in Buffalo was just the opposite. The State Senate had defeated a casino amendment in 1997, so Pataki got gambling by using Indian lands and compacts, an end-run around the state constitution. Buffalo voters were allowed to speak at a special Common Council hearing, but the council paid no attention to what they said. There were never any studies done of the casino’s impact. It has all been based on patronage and politics.

What next?

At some point the Senecas might decide the continual legal battling isn’t worth it, but that’s not likely. They’re minting money in Niagara Falls and they can afford to support a platoon of lawyers.

It might be that Buffalo gets a mayor who is willing to look at the economics of a downtown casino rather than the political advantage of the patronage jobs it might bring and there would be a new governmental voice joining the plaintiffs in federal court and speaking out at the EIS hearings. It might be that the congressman in whose district the casino falls, Brian Higgins, decides that it will do so much harm to the waterfront project on which he is developing his reputation that he’ll be willing to go public and say he thinks a downtown casino sucking huge amounts of money out of the city is the antithesis of development. Perhaps politically and financially powerful businessmen like M&T boss Robert Wilmers, who recently said at a control board hearing that he strongly opposed casinos and thought this one was a terrible idea, will get off the fence, take a public stand and apply some of their vast resources to the public’s good.

Lots of things could happen, and they could, in turn, influence agency decisions and judicial attitudes.

Complex lawsuits rarely end. People get tired or run out of money and they stop. That’s why so often in such cases the public gets screwed. Citizens who organize to stop what they perceive as civic abominations hardly ever have the deep pockets of those who expect to reap big bucks at the end of the process. The Senecas were prevented from setting up shop in Cheektowaga not because of the civil feeling of citizens in Cheektowaga, but rather because Buffalo businessman and casino advocate Carl Paladino underwrote the lawsuit that forced everyone to return to Buffalo.

But then Buffalo got lucky. The city’s second-largest foundation, the Margaret L. Wendt Foundation, decided that the downtown casino would do the city such harm that it was worth a major investment to keep it from happening. And a large number of community members contributed money to help that effort. Citizens for Better Buffalo was able, using those contributions and the Wendt support, to mount two lawsuits that have now cost a million dollars.

The opponents of a downtown casino aren’t going away; they’re not wearing out and they’re not running out of money. They don’t have as much money as the casino operators—who does?—but they have enough to stay in the game.

Moving on

The action now moves to Washington, DC, where the waffling of the Buffalo-Niagara Partnership and the Buffalo News, the hawking of Carl Paladino, the wishful thinking of Michael Powers and the patronage needs of City Hall will all carry little or no weight. Washington is undergoing an identity makeover. The Democrats control Congress, so the rubber-stamp relationship with the Department of the Interior and other agencies for most of the last six years is gone. Jack Abramoff, the lobbyist who spent millions influencing or pretending to influence casino deals, is in prison, his connections and projects are the subject of a huge Justice Department investigation, and people at the Department of the Interior are far more careful than they were two years ago about improper influence.

People can speculate about what’s going to happen next, but, save for one thing, nobody knows with any certainty at all. The one thing is this: Whatever the NIGC decides, the displeased party will be back in court. We’re not close to hearing the fat lady sing. The curtain just came down on Act One. Enjoy the intermission.

Bruce Jackson is SUNY Distinguished Professor and Samuel P. Capen Professor of American Culture at UB. He edits the Web journal BuffaloReport.com and is vice president of Citizens for Better Buffalo.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n3: No Deal on the Buffalo Casino (1/18/07) > No Deal on the Buffalo Casino This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue