The Kingdom Comes

by Peter Koch

It’s tempting to refer to veteran novelist Howard Frank Mosher as “the Vermont author,” a phrase that carries all the weight and meaning of being a regional author. Frankly, Mosher himself now agrees with the billing. After all, he’s penned (yes, Mosher still drafts with pen and ink, furiously filling legal pads at a rate his typist can barely keep) 10 books focusing on and informed by the variously personable, eccentric and recalcitrant personalities that inhabit the rocky corner of the world that he loves and calls home, Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom.

But the title that truly befits Mosher is “honest-to-God storyteller.” His writing is a contradiction in terms: raw but lyrical; straightforward but beguiling; regional but universal. Whenever I picture Mosher, one image comes to mind, a photograph that accompanied an interview with The Atlantic Monthly Online. In the picture, a younger Mosher stands on a bridge, bedecked in a flannel shirt, jeans and a pair of work boots. He’s looking somewhat warily into the lens, his hands shoved in his pockets in a manner that emobodies the characters of the frontier that he creates—both humble and defiant. Mosher might not realize it, but he’s become as much a character of “the Kingdom” as it’s become a character in his books.

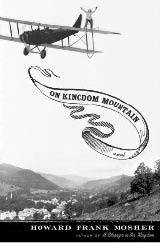

Mosher will appear at 7pm tonight (Thursday) at Hallwalls at the Church (341 Delaware Avenue). Mosher is a showman and an author and, as such, he will present his humorous slide show “Where in the World is Kingdom County?” and discuss all aspects of his writing. In addition, he’ll read from his latest novel, On Kingdom Mountain.

Mosher spoke with Artvoice recently from the wilds of a Lansing, Michigan strip mall, where he was preparing for publicity stop number 60-something on his grand book tour.

AV: Tell me about the Northeast Kingdom, and how the North Country has served as your muse over the years.

Howard Frank Mosher: Well, I grew up in upstate New York in the Catskill Mountains and also in Cato. When I graduated from Syracuse University in 1964 and married Phillis, now my wife of 43 years and my former high school girlfriend, I knew I wanted to write but I had no idea how on Earth to go about doing it. I grew up in a storytelling, sort of Dickensian family, and my refrain as a kid to all of my many eccentric relatives was “Tell me a story.” And they had a lot of good ones, so I knew that was what I wanted to do. But I thought there was a blueprint out there some place, and if I could find a blueprint for how to do it I’d be all set.

AV: You mean there isn’t one? [Belly laughs.] If there is, and you ever find it, please call me immediately, because it would save me an awful lot of time involved with each new book.

But I thought that maybe if I went to graduate school that’s where I would find it. We didn’t have a penny of money, so we decided to teach for a couple of years and then go to graduate school. We heard about two teaching jobs in the Northeast Kingdom, so we ventured up there in the late spring of 1964. My goodness, we fell in love with it the first day there. It was the last day of April, and it was spring in upstate New York, but it was still winter in northern Vermont, so the lakes were frozen. But the Willoughby River in Orleans, where we lived our first year in the Kingdom, was open and the superintendent took us down. The rainbow trout were making their annual spawning run up the Willoughby up to their spawning beds, and we looked down and saw these massive fish jumping the falls, and we looked at each other and looked at the superintendent and said, “Where are those teaching contracts?” Within two or three weeks, we knew we had really come to a frontier. There were people in the Northeast Kingdom in the the ’60s who dated back to the Prohibition era and the Depression, and who had wonderful stories to tell. I realized that I had found a gold mine of unwritten stories. I think when we first moved to the Kingdom, the only thing anyone had ever written about it was Robert Frost wrote one poem set on Lake Willoughby called “A Servant to Servants.” And other than that it was untouched, unexplored by any writer. So we intended to stay a year or two and save a little money and go on to graduate school and, in fact, we are still there and I haven’t run out of stories yet.

Our landlady told us a hell of story the first week we were there. She said that during the Depression she and her husband were having difficulty holding onto their farm, and it was about to go under. So she put to use the only thing her father had ever taught her, which was how to make moonshine. She made just enough to keep that farm going during that Prohibition era, and as she was running the shine off one night by lantern light, she looked up and she saw, across the little brook where her still was located, she saw what she described as “a pair of city shoes with a guy wearing a city suit standing in ’em.” And she knew he was a revenuer, and she said to him, “You can arrest me if you want, but I want you to know that if you do we’re going to lose our place.” When she looked up again he was gone. They were able to hold onto the farm. Then her husband died rather suddenly, so she moved to the nearby village. One night a few years before we showed up, there was a knock at her door. She recognized the guy standing there in his city shoes and suit, and she said to him, “Have you come to arrest me again?” And he said, “No, this time I’ve come to marry you,” and he did. They were very happy together, and later on he died very suddenly. When she finished telling us all this, she looked at us and she said, “You know I’ve had a very good life, but I just haven’t had good luck keeping my husbands alive.” At that moment I knew I was going to write stories about the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, and that that was what I was going to dedicate my life to.

AV: She later appeared in one of your books, didn’t she?

HFM: She did. She appeared in Where the Rivers Flow North, and I wrote that story just about the way she told it to me. That’s the only time I’ve ever done that. Then I sent that story to the University of California at Irvine, to their MFA writing program, still thinking maybe I could go find the blueprint. I was accepted. We went out to California and stayed exactly a week. I felt just cut off from all my material back in Vermont that I was just beginning to understand well enough to write about it. I had an epiphany. My wife said, “Let’s go for a ride and see if we can get some perspective on all of this.” We wound up, just by chance, at the intersection of Hollywood and Vine in downtown Los Angeles, and a telephone truck pulled up beside us. The driver probably had seen our green Vermont license plate, because he rolled his window down and said, “I’m from Vermont, too. Go back while you still can.” And we did, right on the spot.

When we got back, I went to graduate school. My graduate school was working in the woods for the guy, Jake Blodgett, who told me many of the stories that later wound up in Disappearances and also became the inspiration for Noel Lord in the short novel in Where the Rivers Flow North. So that was just be sheer chance that I went back to Vermont, met him, worked in the woods and wrote Disappearances, but I’m glad it turned out that way.

AV: Do you ever tire of being classified as “the Vermont writer?”

HFM: Well, it used to bother me, but it doesn’t so much anymore. I think that it’s hard for me to see myself as anything more than a regional writer. I live in a fairly distinct region of the country and even of New England. It’s still a little isolated and cut off from the rest of Vermont, even today. It’s the place I write about. And, for better or for worse, that’s what I am, a regional Vermont writer. I take some solace, not to make egregious comparisons, that so was Faulkner, so was Frost.

It used to gall me that people called me a regional writer and reviewers called me regional writer, but what the hell, I am what I am. I’m 65, for one thing, so it’s easier to see maybe what I am and what I’m not. I know that regional writing can be very bad, and I know that some regional writing is also provincial, and I try, in my work, to avoid that when I can. There’s a phrase that I’ve heard beyond the Northeast Kingdom, but I hear it a lot in the Northeast Kingdom: “So-and-so is who he is.” With Jake Blodgett, the logger I used to work for, people would say, “Jake is who he is,” meaning he’d lived out on the fringe of the law but at the same time that was the way he’d grown up and, for better or worse, that’s who he was. So I guess I am who I am.

AV: At the beginning of North Country, you write, “I can’t shake the feeling that here in the North Woods of New England, I’m witnessing—like Nick Adams in the Hemingway story—the end of something.” A lot of your writing celebrates this severe but bountiful land, and a culture that is disappearing. Do you see your writing as an effort to preserve those two things?

HFM: It is, to some extent. Mainly what I’m trying to do is tell the best story that I can. Certainly, the driving idea behind both Disappearances and the new book, On Kingdom Mountain, is the vanishing…not so much wilderness—it’s not the kind of big woods that you get in northern Michigan or northern Maine—but the unspoiled countryside. A few years ago, I was walking on the mountain across the road from my house, which is still relatively unspoiled, undeveloped. I had a terrible image of it being covered with housing tracts and McDonald’s and Wal-Marts, and I think that’s what suggested the idea of On Kingdom Mountain, an endangered mountain.

And how I came up with the main character, Miss Jane Kinneson, I’m not sure. I think she’s inspired by a combination of real people—my great aunt Jane, to some extent, my wife, who’s a high school science teacher and guidance counselor and loves nature, our first landlady and a friend of ours named Margery Moore, an Abenaki woman who has figured in my work. Yes, that’s definitely a theme in a lot of the things that I’ve written, including Where the Rivers Flow North, where Noel Lord’s realm up in the bog is being threatened by the power dam.

The Northeast Kingdom is not as developed as the rest of Vermont, but there are all kinds of signs that it’s coming—much more posted land, a lot of land owned by people who live out of state and bought it as investors, more second and third homes cropping up, especially on hilltops. And, of course, even around the little towns in the Kingdom like Newport and St. Johnsbury there are the strip malls, like the one I’m looking out the window at right now in Lansing (laughs).

One thing I do to try, I don’t know, not overcome or counteract—but that’s just a reality in that I do write about just one region—is when I finish a book, I try, at least, to spend some weeks promoting it nationwide, to keep building at least a small audience beyond New England. I’ve found, especially this time out on the book tour, that it seems to be paying off. You know, I’m not going to go from being a middle mid-list author to being a bestselling writer just because I’m visiting bookstores nationwide, but it does help with building a somewhat better audience outside Vermont and New Hampshire.

AV: This is the biggest tour you’ve been on, correct?

HFM: Well, it’s the biggest, but I guess this is the fourth time I’ve really hit dozens of stores and libraries in cities nationwide…it’s literally a hundred different towns and cities by the time I finish this in December. I would say it will probably result in a few thousand more copies sold than had I not taken it. But when you’re dealing with sales figures of 12-15,000 in hardcover and maybe 20-30,000 in paperback, a few thousand can make the difference between an advance for my next book that I can live on and one I can’t. There’s something insane and desperate about it, too, I recognize that.

As there is about Disappearances, come to think about it. I wrote that book under the gun. It was do or die. I was either going to write a novel and find a way to publish it or be a school teacher for the rest of my life. My wife and I had tiny kids and she was not working at the time, but with her support I quit my teaching job and we sold our house. We got about $3,500 in equity out of it, and lived for one winter while I wrote Disappearances.

AV: That’s quite a leap of faith.

HFM: Well, it was. But, again, there was a strong element of desperation in it, too. It’s revealing, though, because there really isn’t a blueprint. There are as many ways of going about writing as there are writers, and I just think that a writer has to find his own approach.

AV: Describe your writing process.

HFM: Well, my novels take an ungodly amount of time, and I’ve never been able to figure out why that is. I wrote Disappearances quickly, I guess, because I had to. But A Stranger in the Kingdom was a seven-year write and The True Account took six years. I can work on more than one at a time; sometimes I work on one in the morning and another in the afternoon.

Generally, I work about the same hours my wife does—from early morning right straight through until late afternoon, sometimes on into the evening. I like to try to break my day up by going up onto that mountain across the road from our house around noon for an hour or two. There are still a dozen or so good trout brooks up there. I gave up hunting a few years ago, and I don’t know why. So I don’t hunt up there anymore, but I like to hike and cross-country ski in the winter time…Other than that, though, I just write, and my books often go through 40 or 50 different drafts, though they’re not all entirely different from each other, I’m sure.

The new book, On Kingdom Mountain, I’m sure went through 50 drafts. It was a five-year write, and I really didn’t get the handle of it until the last year when the stunt pilot who shows up on Miss Jane’s mountain looking for treasure appears, and then there was someone up on the mountain for her to talk to and have both a relationship and some conflict with. That seemed to be the key to that book, but why it would take me so long to figure that out, I don’t know, but it often does. And there’s something almost obsessive about it, too, once you get started with a book and you know you have a promising idea but you haven’t reached the heart of the book yet, where every sentence you read is driven by some kind of emotional force. And, it seems to me, the breakthrough often comes with a character, some insight into a character or maybe introducing a new one. I would say I work 60 to 70 hours a week, and sometimes I feel, at the end of the week, that I’m no further ahead than I was at the beginning.

Mosher looks forward to his Buffalo visit…anything to get him away from that godforsaken strip mall.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n33: If You See a Gringo with a Camera, Shoot Him (8/16/07) > The Kingdom Comes This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue