Next story: Letters to Artvoice

About Face

by Eric Jackson-Forsberg

The genre of portraiture is a perennial favorite for artists and collectors alike, as demonstrated by About Face: Portraits from the Gerald Mead Collection, at the Fanette Goldman/Carolyn Greenfield Gallery, Daemen College, now through September 28. This latest installment of thematic exhibitions culled from Mead’s personal collection includes a wide range of artists’ portraits and self-portraits, organized through the lens of Western New York associations.

This cross-section of Mead’s collection immediately demonstrates the historical depth of the collection: from an 1883 ink drawing by Frank Penfold to a 2007 collage by UB MFA candidate Colleen Cunningham. In between is a who’s who of Western New York artists, including Robert Longo, Cindy Sherman, Milton Rogovin, William Y. Cooper, Marion Faller, Bonnie Gordon, Peter Stephens and Arnold Mesches. The work, in a wide array of different media, is grouped in aesthetic-thematic matrixes in the intimate space of the gallery, inviting the sort of organic juxtapositions that make such an installation so enjoyable.

Perhaps the logical place to start with this exhibition is Milton Rogovin’s Atlas Steelworker triptych from his Working People series, a classic example of Rogovin’s elegant documentation of the unsung heroes of Buffalo’s heavy industrial age. But one of the most poignant pieces in the show is a portrait of Rogovin himself by Paul Francis Canorro. The product of Canorro’s project to depict elderly artists in their studios, this photograph shows Rogovin as legendary Western New York photographer in the “natural environment” of his basement studio, surrounded by equipment and supplies. This simple image makes for a wonderfully self-reflexive dialogue between artist, subject and media. A photograph very much in the mode of Rogovin’s own images, it draws on centuries-old portrait traditions of depicting the sitter with his or her attributes, the trappings of their occupation or identity.

Turning to a very different mode of representation, Philip Burke’s Henry Kissinger provides a prime example of how the most telling portraits may not be the most naturalistic. Burke’s signature swaths of distorted color and form accentuate the subject’s most characteristic features (the nose and heavy black glasses, in Kissinger’s case). The funhouse mirror of Burke’s Pop-Expressionist style reflects the subtle distinctions between portraiture and caricature.

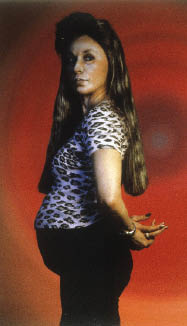

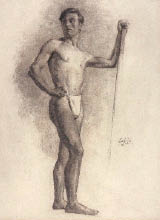

Two of the most compelling works in the exhibition might be described best as “anti-portraits:” Cindy Sherman’s untitled photograph and the untitled figure study by Hal English. Sherman’s work invites us to question the definitions of portraiture and self-portraiture. The figure, of course, is Sherman herself as one of her lurid, dress-up characters: a young mother-to-be posing before a pulsating red background. The figure stares defiantly at the camera, invoking something of Klimt’s scandalous, allegorical portrait, Hope. Although this is technically a self-portrait, Sherman obscures her own identity by wrapping herself in a stereotype drawn from the back of the cultural closet—an anti-portrait on all counts. Hal English’s figure, in turn, represents a case of the “accidental masterpiece”—the nude model from a life drawing class elevated to idealized subject. The naturalism of this drawing invites the introspection of portraiture, but the attributes of prop staff and loincloth underscore the academic objectification of the figure.

Another grouping of works in the exhibition juxtaposes portraits with figures that turn away or are otherwise obscured, as if to resist the essence of the genre itself. Kevin Charles Kline’s piece in this group, Self Portrait with Megaphone, obscures all but the mouth and neck of the figure with a megaphone, suggesting self-imposed silence but also a makeshift dunce cap. Joseph Piccillo’s photorealist figure is marked by crosshairs of shadow, as if to analytically map the contours of the face. These works offer a subtle critique of the prime expectation of portraiture: that it convey the most revealing qualities of the sitter.

The exhibition features many self-portraits, some identified as such and some anonymous. Josh Iguchi’s St. Sebastian is a wry self-portrait of the artist as the brutally martyred saint. The neon-lit figure in Converse sneakers is Iguchi in front of his own camera, while the Biblical reference is achieved by piercing the print with real nails.

In the course of its survey of Western New York artists, About Face also demonstrates that each portrait tells a story. Charles Haupt’s Lukas Yearning, for example, whimsically documents a particular quirk of the former BPO music director’s work habits: He could never be far from a telephone. The study for War Story: Soldier Guarding Pump, by retired Daemen professor of art Jim Allen, is a portrait of a contemporary soldier but also an allegory of current geo-political conflict even more timely today than when it was created in 2002.

Whether it’s such ripped-from-the-headlines types or more intimate biographical profiles, the work in About Face represents a genre that is familiar, but which cannot be taken at face value.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n38: About Face (9/20/07) > About Face This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue