Next story: Free Will Astrology

Biennial X 2

by Becky Moda & Eric Jackson-Forsberg

Last week, the biennial Beyond/In Western New York exhibition opened in major 12 galleries throughout the Buffalo/Niagara region. The exhibition features the work of 50 artists and is the fruit of two years of collaborative work involving the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Big Orbit, Buffalo Arts Studio, the Burchfield-Penney, the Carnegie Art Center, the Castellani, CEPA, El Museo, Hallwalls, Squeaky Wheel, the UB Anderson Gallery and the UB Center for the Arts. Beyond/In serves as a cultural exchange between the local curators and artists in Western New York and the adjacent communities of Southern Ontario, Northern Ohio and Central New York.

It’s too much for one person to tackle in one week, so in this issue our two reviewers initiate their rolling, four-week coverage of the biennial’s exhibits. They begin with three venues: the Albright-Knox, El Museo and Hallwalls.

Albright-Knox Art Gallery

The power of the sculptural installations at the Albright-Knox is immediately apparent as one looks across the sculpture court toward the Beyond/In Western New York galleries. Shayne Dark’s outdoor sculpture, Into the Blue, framed in the far window, Lyn Carter’s central form of Courting Entasis in the middle gallery and Artemis Herber’s Walls of Love undulating out into the court form a stunning vista along the central axis of the exhibition. Contrasting colors and forms spill out of the designated space and draw you into the exhibition—as if the galleries couldn’t hold it all, or the art couldn’t wait to be seen.

Artemis Herber’s standing ribbons and curls of Valentine-red cardboard inhabit the large, central gallery as well as the entry colonnade. Some of these forms embrace the building’s ionic columns like lithe, sanguine forces made material, their color and form in rich contrast to the white, symmetrical marble. Other sections of these “walls” curl onto themselves to form mysterious teepees. Herber’s architectonic sculptures question the distinctions between positive and negative space with simple materials and a seductive power.

Lyn Carter’s installation—created especially for one of the Beyond/In galleries—presents other surprising sculptural possibilities. Courting Entasis is an extreme illustration of the slight bulge in the middle of classical columns (entasis) that reflects their load-bearing function. Here, columns of blue-and-white striped fabric swell and diminish repeatedly on their implied journey from floor to ceiling (or vice versa) like sculptural pythons digesting a recent, formal meal. The precisely aligned blue and white stripes of the fabric Carter uses encourage the eye to track over the pieces’ fascinating curves, but may also be a whimsical nod to the Greek flag, drawing another connection to classical architecture. Carter’s work has a simmering eroticism as well in the allure of the tightly wrapped, swelling forms.

The vista of sculptural installation ends outside the Gallery’s walls with Shayne Dark’s Into the Blue. This piece looks like it has always been at home amongst the primary-colored forms of the Gallery’s outdoor sculpture collection. Like Anish Kapoor’s blue-pigmented forms, Into the Blue resonates with a supernatural energy, swaying gently in the wind and harmonizing with patches of clear sky. Dark’s installation suggests a metaphor for growth, as if to compensate for the many arboreal casualties of last year’s devastating October storm, the scars of which are still evident in the Buffalo treescape, just beyond the sculpture.

The installation continues with Ani Hoover’s vibrant paintings. Created on Yupo synthetic paper, these compositions have an inherent slickness that Hoover exploits not for the sake of a seamless surface, but for the amazing sense of movement implied. White Collide, for example, invokes the explosive energy of a fireworks display, underscored by the red, white and blue palette. Memory alludes to the slickness of the materials on another level, as the banner of Yupo paper seems to slide off the gallery wall and down onto the floor. On the opposite wall, Hoover’s grid of small works offers hours of delectable aesthetic contemplation, and demonstrates that her vocabulary of drips and disks works on a small scale as well.

Turning to another selection of small-scale paintings, Amanda Besl’s intimate oils offer glimpses of female coming-of-age. Beautiful and awkward in turn, these are not so much portraits of individuals, but of moments that define (or defy) female adolescence. Besl considers herself a “miniaturist,” working in a hyper-realistic mode facilitated by precise tools such as razor blades and cat whisker brushes. The tightly contained nature of her working method seems to reflect the introspective nature of the subject, the narrow arenas still imposed on young women.

One of the most intriguing “paintings” in the exhibition is not technically a painting at all: Lois Andison’s time and again. A video made up of sutured digital stills, this work combines static and kinetic media, retaining the benefits of both. Andison took thousands of still images of her Toronto backyard—every half hour for a year—and the results are uniquely captivating. This document allows the viewer to contemplate both small and large changes in this otherwise ordinary vista—an animated landscape that inspires meditation on the nature of time and the exquisite beauty that may be found in patient observation.

From the sublime to the ridiculous—Simone Mantellassi’s frenetic installation of small, mixed-media works channels a flood of images and influences through a fire wire connection to art history, comics, and a psychoanalytic circus. His rapid-fire commentary on the audio guide explains that experiencing his work is like “going inside the head of someone not quite normal.” There, “[he has] a big monster trying to come out.” To the extent that he—or anyone—can analyze this visual onslaught, Mantellassi sees his work as a sort of doodle therapy, sanctioned by Hunter S. Thompson as much as by Walt Disney.

If the wilder side of the aesthetic trickster is behind Mantellassi’s work, the more amiable, fun-loving side is alive and well in the work of Chris Barr. Barr’s Bureau of Workplace Interruptions is an installation, Web-based and performance project that seeks to “slip its way” into the Dilbertesque world of corporate culture to provide a little comic relief. Visitors to the installation may sign up for a workplace interruption via an internet connection of by filling out a rack card. The bureau’s “office” installation is decorated in the corporate palette of gray, taupe and faux wood-grain, suggesting that the bureau’s success lies partly in deception; it’s disguised as just another “consultant” to the corporate system in order to subvert the same.

When taking in Beyond/In Western New York, don’t miss the work of Alfonso Volo in the small sculpture gallery. While some of the assemblages and drawings are displayed in the glass cases once reserved for antiquities and decorative objects, other elements dangle from doorway moldings or overhead like spider webs, or seem to scamper into corners like the mice and rabbits of Volo’s iconography. The traces of such small, quiet creatures are everywhere—shadows, tracks and gnawed wood chips—inciting both fear and fascination at every turn. Spending time in Volo’s environment is an eerie experience of discovery; no niche is left untouched by his skittering interventions. The audio guide is an essential component of this installation: Volo’s “artist statement” is a surrealist manifesto that cites poetic inspiration from Emily Dickinson to Laurie Anderson. But in the end, Lewis Carroll might be the most appropriate literary companion when venturing down this rabbit hole.

—eric jackson-forsberg

The mother of the Beyond/In exhibition, the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, makes a pitch for the eclectic. Toronto artist Kathryn Ruppert-Dazai’s unique work combines a painter’s sense of composition with an unorthodox, outsider medium: crochet. These “knitted paintings” have an amazingly tactile, three-dimensional quality; for me, it was impossible to view the work without imagining how it would feel to touch. I touched it and was asked by security to step away from the work. The magic of her work lies in the stark contrast between her folksy, inviting medium and her traumatic subject matter. Pieces like The Miscarriage and The Puking depict small, solitary and crumpled figures, huddled in the corner of yawning, monochromatic, almost cruelly soft backgrounds. Other figures in her work, almost tribal in their ghoulish rigidity, seem to hover over their backgrounds due to bold color and fabric juxtapositions (materials include wool, felt, mohair angora and shredded satin).

Kristan Horton’s transformative work is the result of what appears to be an intense obsession with Stanley Kubrick’s classic film, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. The artist, who has seen the film several hundred times, has taken many frames from the film and created diptychs, pairing each still with a near-identical photo, substituting mundane items—forks, markers, popcorn—for the various bombers, soldiers and explosions in the film. The effect is at first confusing, then revelatory as it gradually dawns on the viewer what they are looking at. The Orwellian phrase “peace is our business,” seen in more than one of the photos, seems in this context to be a comment on the inherent madness of the war machine, from the dawn of the cold war to the war on terror. But more than that, Horton’s work is about vision and illusion. It surprises us with how much a couple of eating utensils can look like a B-52, given a prior suggestion. This transformational effect is further enhanced by a stop-motion film in which common products—a cigarette pack, a can of coke, a sardine tin, etc.—are manually transformed into one another. While Horton’s political subtext strengthens the impact of his work, his focus seems to be the fluidity of form, the distinction between form and content, and the way our brains recognize what our eyes are seeing.

The excitement of Chris Barr’s Bureau of Workplace Interruptions is not so much in the “branch office” exhibit at the Albright-Knox—a somewhat retro-styled office environment—as it is in the service his “time-stealing agency” offers. It’s truly an ambitious concept. Barr takes pranksterism to the micro level—your own sunless cubicle. Workers are encouraged to request an interruption—ranging from a simple e-mail to an on-site visit and once the bureau has determined the appropriate way to do so, they interject themselves into your workday, hoping to change it in unexpected and beneficial ways, without tipping off the boss. While delightfully humorous in its style and presentation, Barr’s project can also be seen as a form of resistance against worker exploitation: Where does the self wander to in the hum of a gray office?

Jeremy Bailey’s film, Transhuman Dance Recital, No. 1, 2007, warmed me from the inside out. When you arrive in the gallery you see bright, streaming horizontal lines of vinyl extending from the projection wall. Bailey’s work is comical, and his onscreen persona seems a parody of artistic self-importance. I assume it’s Bailey’s head floating on the screen, attached to four low-res tentacles. He explains how music gets into his soul and makes him a little nervous. Then he dances with a smiling triangle. The retro quality of the graphics—think ColecoVision—is reinforced by the accompanying music, New Order’s 1986 hit “Bizarre Love Triangle.” On its face, this piece is just plain silly, but the viewer’s initial reaction—what does this guy think he’s doing, making art?—gives way, for me at least, to a real delight that something this funny found its way into a “serious” art show.

—becky moda

El Museo Francisco

Oller y Diego Rivera

El Museo features the work of Chinese expatriate painter Xiaowen Chen. The selection of paintings from the Great Smoke series references the long tradition of smoke and cloud motifs in Chinese bronze and painting. But Chen often utilizes the cloud or smoke forms as windows of negative space—windows opening to other realities based in tourism and expatriation, western colonialism, family and the gaze. The latter is represented by figures peering through telescopes, apparently striving to bring distant scenes closer, as Chen does with his paintings in general. Chen employs a broad vocabulary of drawing and painting techniques, with a color palette of sherbety pinks and greens. The fluffy, translucent forms and layering of imagery in multi-panel works like Once Upon a Time suggest contemplation of a past that is distant in both space and time.

—eric jackson-forsberg

Hallwalls

Contemporary Arts Center

Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center is housing a number of works which blur artifice and reality. Everywhere in Roberly Bell’s Becoming Blurred exhibit, the synthetic pushes against the organic. Influenced by blob architecture (or blobitecture), the application of organic, amoebic form to buildings, Bell’s brightly colored “flower blobs” seem organic, but are computer-designed, and they burst with artificial life—plastic flowers, birds and crickets adorn these garish habitats, which erupt from the floor, the walls, and wrap around a beam in the gallery. Fake butterflies line the walls. On a flat-panel TV, a lone live cardinal seems to be trying to escape its electronic confines. Bell’s work challenges our notions of what fake and real are, and evokes the irony of human efforts to mimic the natural while destroying the actual.

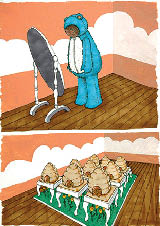

As you leave Bell’s room, her butterflies seamlessly turn into a stream of plastic birds, drawing you into Adam Weekley’s Ravenous. Atop a square platform of Astroturf and artificial flowers sit several chairs, each of which supports a plush, well segmented beehive sewn with ornately patterned fabric that you might find in a well-to-do suburban dining room. From each of the hives spills a pile of honey-colored butterscotch candies. In a corner, against a pink-painted wall with clouds, stands a life-sized, bright blue bear suit. But the suit is empty inside. With a transparent shield for a face like some outlandish beekeeper uniform, it balefully regards itself in a mirror, hands full of the same candies, as if examining its own need for more-more-more. On an opposite wall hang small, framed drawings, a vignette of a young boy getting stung by bees.

David Clayton’s installation is an adventure into boyhood, or the idealization of a standardized American boyhood from the 1950s. Clayton’s work captures the hope and innocence of youth, along with its rough awkwardness. The crude materials—blue plastic tarp and particle board—wall them in to form a pastiche bunker. The most prominent piece of his at Hallwalls is something like a tent, filled with the obsessions of a model boyhood—superheroes and military hardware, a cot with superhero sheets—and topped with a giant plastic hamburger, portraying the mass marketing that underlies these obsessions.

The concept of Stephanie Rothenberg’s School of Perpetual Training is brilliant: a video game about the video game industry. Rothenberg uses classic arcade games to “train” the viewer for several unskilled jobs, while illuminating hidden facets of game production: Dig-Dug for coltan mining, Tapper for circuit board assembly, Space Invaders for “box build” and Tetris for ship-loading. The process not only teaches viewers the full impact of a single class of consumer product on the world, but also has the alarming effect of placing the viewer in the roles of third-world workers, forcing us to truly consider what those lives might be like. This theme is further emphasized by the placement, via a hidden camera, of the viewer inside the game itself. The interface of Rothenberg’s video game utilizes motion capture technology to make your body the game controller, requiring full body movement to play, or “work.” It’s a strong, wry statement about globalization and luxury in time for the dawning shopping season.

—becky moda

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n39: Into the Biennial (9/27/07) > Biennial X 2 This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue