Theaterweek

by Anthony Chase

IT AIN’T NOTHING BUT THE BLUES

They produce musicals lavishly at the Paul Robeson Theatre, and they certainly have not skimped on their current musical revue, It Ain’t Nothing But the Blues, which boasts an onstage jazz band and a cast of six. Frazier Tom Smith has provided the musical direction. Mary Craig has directed and the very handsome set is by Harlan Penn. This is a hot evening of entertainment, in which the capable cast takes us on a cruise of blues history, one song after another, from traditional African music to late 20th-century popular music. Along the way we hit “St. Louis Blues”; “Let the Good Times Roll”; Hank Williams’ “Mind Your Own Business”; the Patsy Cline hit, “Walking After Midnight”; the Peggy Lee hit “Fever”; the disturbing yet haunting “Strange Fruit”; “Goodnight, Irene”; and at least a dozen more.

Mary Craig herself joins the cast and makes seemingly easy work of numerous numbers, succeeding most memorably with her ribald audience interactions. Beverly Crowell is similarly fine as well. The men of the cast—Terry Wideman, Don Allen Hunley and Julius “Shorty Long”—are uncommonly strong and sell the songs with zest. Kenya Hall’s choreography is appealing and her dancing is especially memorable in the opening African sequence.

The revue is designed to educate, but most importantly to delight, and the production excels at the task.

BOILERMAKERS & MARTINIS

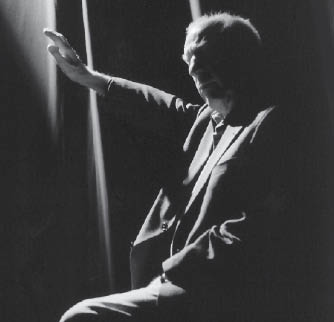

One could argue that Boilermakers & Martinis is not theater at all, for in this autobiographical evening, Emanuel Fried portrays himself as he narrates his own double life as working-class union activist (boilermakers) and society husband (martinis). And yet there is, in the process of storytelling, the inevitable selection and condensation of detail that we associate with fiction. Certain events are highlighted, while others are undoubtedly left out or modified, intentionally or not, by memory, loyalty or emotion. Ultimately, our lives are unknowable, even to ourselves.

What we receive, over the course of this intriguing performance at the Road Less Traveled Theatre, is the weaving of the myth of Manny Fried, with one foot firmly planted in fact and the other in the subjectivity of reminiscence. When the story has been told, certain truths have been revealed and certain mysteries linger. I found the experience entirely captivating.

While Manny himself is decidedly the hero of his own life, finding the antagonist is more elusive. He begins his narrative by repeating a question that was once put to him, “Looking back, is there anything he would have done differently?” The question turns out to be the torment of his life, for certain decisions in his past left those he cared about vulnerable to suffering that he never intended.

Manny’s story is well-known locally. A working-class Jewish boy from Buffalo’s East Side, in 1941 he married Rhoda Lurie of the socially prominent family who owned the Park Lane. She thought she was marrying an aspiring actor. What she got was a rising union activist who was on the FBI’s red list during the McCarthy era. Unable to thwart Manny’s union activities directly, the FBI sought to undermine him by going after his wife and daughters.

In Manny’s telling of this real-life drama, the role of villain is assigned and reassigned repeatedly. Sometimes the villain is smug but ethically bankrupt neighbors or weak and frightened relations. Sometimes it is the press. Sometimes Manny himself is the destructive force; sometimes it is his wife, Rhoda. Always, however, there is the hand of the government, making life a nightmare for the Fried family. Agents visited all their neighbors. They found their daughters dropped from carpools and children’s parties. Close friends and even relatives turned on them.

Establishing the FBI as the overarching super-villain would seem to resolve the issue and absolve everyone of guilt, but it does not. In Fried’s tale, as the government pushes the lines further, isolating the Fried family, the dilemma is reconfigured. New challenges emerge. Should Manny cave in to the FBI and cease his union activity for the sake of his family? And when he does not, should Rhoda stand by his side, watching everything else that is important to her slip away, or should she take her children and salvage the world she knows by divorcing him?

In the end, the couple cling to each other and weather the storm in a kind of tortured co-habitation that even they, we learn, never entirely understood. Everyone suffers, husband, wife and children, but none more, suggests Manny, than Rhoda. While this retrospective realization disturbs him, the idea of giving in to those who forced this hell upon them disturbs him even more. When he presses the issue, Manny arrives at the ersatz Latin aphorism of the World War II era, “Don’t let the bastards grind you down!” This, he suggests, in tentative yet forceful fashion, is the lesson of his life.

At 94, Manny Fried endures. He has lost Rhoda and he has seen the factories he helped organize close, one by one. For most Buffalonians, the idea of the Red Scare seems remote and otherworldly. The idea of a time when Buffalo socialites drank and dined at the Park Lane seems like a storybook. And yet, this story resonates with undeniable relevance made all the more powerful by the fact that Manny himself is here to tell it.

Some of the personalities from Manny’s story are still in town and judiciously (or kindly) he does not name certain names. No matter. Those whose deeds have been condemned by history have become irrelevant. How did it help them to turn on their neighbor, except to lend them a certain ephemeral sense of superiority or access to power?

By the same token, how much has changed, really? At a time when we learn that the outgoing Attorney General approved the unconstitutional wiretapping of thousands of ordinary Americans and we hear that the Lackawanna Six, languishing in prison, may never have posed a threat of any kind, we can reasonably ask, “Who are today’s communists?” Today, as we see UAW workers go out on strike for benefits we thought were negotiated generations ago, we ask ourselves, “Why is this an issue at all? Why is there no national healthcare? Why do we still leave workers vulnerable to the greed of the powerful?”

We look to our elders for the wisdom that comes from experience. Manny Fried feels at a loss to find much deliberate wisdom. Instead, he offers us his life story. He lays out this history methodically, deliberately and with minimal affect. He shares the events. He shares the inner conflicts. Ultimately, he leaves us to decide for ourselves.

THE SEABIRDS

William Orem’s new play, The Seabirds, is a strong two-character piece set in an island lighthouse in Civil War era Maryland. An existential dialogue in which David Hayes plays Laben Shadfield, the deeply religious Yankee lighthouse keeper, and Ray Boucher plays Mickey Leance, an Irishman who has deserted from the Confederate side, the play reminds us of other barren theatrical landscapes in the work of Beckett or Camus, without ever slipping into cliché.

As the play begins, Laben rescues Mickey and nurses him back to health when the boat in which he is escaping crashes on the island. This forces the mismatched pair into a dynamic in which they quickly intuit a great deal about each other, and unintentionally reveal a great deal about themselves and the nature of loneliness and trust.

Directed and designed by Neal Radice, with costumes by Todd Warfield, Alleyway has given the script a handsome and confident production. Orem’s dialogue flows naturally and the reversals in power follow logically and lucidly. Each man’s hidden desires and insecurities propel the minimal action forward in ways that are engaging and unpredictable. Cocky yet paranoid, Mickey becomes convinced that Laben wants to kill him. Repressed Laben seems to want to keep Mickey as a kind of pet and companion. This dynamic twists its way to an unexpected conclusion.

The Seabirds represents some of the best of what the Alleyway is capable of doing, as the company has lavished its talent and attention onto a brand new play by a rising playwright. Recent productions of edgy and deranged work like Reefer Madness is a welcome addition to the Alleyway menu, but it is also important to provide a home for serious new work. As The Seabirds approaches its final weekend, I strongly encourage those who enjoy taking a theatrical risk with something challenging to take a look.

THRILL ME:

THE LEOPOLD & LOEB STORY

When I first saw the York Theatre production of Stephen Dolginoff’s Thrill Me: the Leopold & Loeb Story off-Broadway in the summer of 2005, I thought it was wonderfully engaging and delightfully perverse. It had a compelling score and an original take on the Leopold and Loeb relationship, wherein two young Chicago socialites developed a peculiar and ultimately murderous bond. Briefly, Loeb agreed to engage in sex with Leopold, and in exchange, the latter agreed to participate in an escalating series of crimes. The pair would eventually murder 14-year-old Bobby Franks, just for the thrill.

The tale has intrigued generations of writers, myself included, as evidenced by my own 2001 article, “Violent Reaction,” featured on the cover of Chicago-based In These Times magazine, in which I compared Leopold and Loeb to Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the Columbine High School killers. Indeed, the journey from Leopold and Loeb to Harris and Klebold is not far. The earlier case is seminal in the annals of criminology and psychology both.

The Leopold and Loeb case was the occasion of Clarence Darrow’s famed “never the sinner” summation, in which the celebrated defense attorney successfully managed to spare the boys the death penalty. The tale has often been dramatized, including in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1948 film, Rope; Tom Kalin’s 1990 film, Swoon; and John Logan’s 1987 play, Never the Sinner (produced in Buffalo by BUA in 2000).

When the original York Theatre production of Thrill Me was extended in 2005, the author took over the role of Nathan Leopold. He is reprising this performance here in Buffalo for the New Phoenix Theatre Company, opposite Joseph Demerly (who, interestingly, had played Leopold for BUA in 2000), making this production of the show rather special. The production, under the direction of Robert Waterhouse, is handsome in every detail. The set design by David Butler is efficient and marvelously atmospheric, and this is enhanced by Kurt Schneiderman’s superb lighting. Musical direction by Michael Hake, who also plays the keyboard for the production, is first rate.

In addition to setting the tale to music, the great contribution of Mr. Dolginoff is his premise that Nathan Leopold, universally viewed as the passive partner in the Leopold and Loeb relationship, actually exerted a great deal of control, and that committing the murder of Bobby Franks and getting caught was all part of his plan to stay with his beloved but elusive Richard Loeb forever. In this regard, Dolginoff’s is a marvelously and compellingly post-modern interpretation, evocative of more recent academic discussions of male masochism—but way more fun. In his performance, the author imbues the character with great humor and mischievousness, which bubbles to the surface with unexpected vitality. For his part, Mr. Demerly handsomely holds his own and navigates the material with confidence.

ON GOLDEN POND

On Golden Pond is a comforting and familiar story, best remembered as the screen farewell of Henry Fonda, opposite his daughter Jane, in which Katharine Hepburn memorably called him an old poop and called out to her beloved loons. And yet the piece revives surprisingly well. The recent Broadway production with Leslie Uggams and James Earl Jones closed only because Mr. Jones fell ill. O’Connell & Company, has assembled a first-rate cast to give Ernest Thompson’s 1979 play a very pleasing outing.

Ron Swick, familiar to me only for broadly presentational comedy, turns out to be a compelling and wryly humorous realistic actor. His Norman is endearing and exasperating in all the right ways. Anne Gayley, too, gives a winning performance as Ethel, bolstered by excellent work from Eileen Dugan, David Butler, Tim Newell and young Alex Race. Yes, even the kid is good in this production. That is a first-rate cast.

Mary Kate O’Connell has directed the production, with a set by Mr. Butler.

On Golden Pond is the story of an elderly couple spending what might be their final summer at their summer cottage on Golden Pond. Their daughter, somewhat estranged from her father, has made an effort to reunite, returning with her fiancé and his 13-year-old son from a previous marriage. After that, everything that happens is endearing, but in this production, it never gets icky.

Gayley is far less annoying than Katharine Hepburn was in the film—she even manages to say, “Norman, the loons!” without eliciting laughter—and provides the backbone of the production. David Butler gives a solidly convincing performance as the fiancé. Timothy Newell provides deft comic relief and touching insight as the postman who never finds love. Eileen Dugan gives yet another convincing performance as the daughter who is a woman everywhere but in her parents home. Alex Race manages to play a 13-year-old with great sincerity and believability. Even having seen the remarkable James Earl Jones, a return visit to Golden Pond is a far more pleasurable experience than I had recalled.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n39: Into the Biennial (9/27/07) > Theaterweek This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue