Fame! (But Will They Remember Her Name?): Factory Girl

by George Sax

It became increasingly difficult to stop thinking of the late Anna Nicole Smith as I sat through a screening of Factory Girl the other day. The movie wasn’t about her, of course. It’s an ostensible biopic about Andy Warhol acolyte Edie Sedgwick, who crash-dived to her death from a narcotics overdose at the age of 28 in 1971 after an abbreviated life of dangerous, dead-end excess.

At first blush, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of common personal ground between Sedgwick and Smith, other than drugs. Smith, the ex-Playboy model and gold-digger extraordinaire who died in suspicious circumstances last week, lived much louder and larger than Sedgwick, the escapee from New England wealth to the downtown Manhattan bohemian enclave of Warhol and his crew.

Smith took a severely limited complement of personal assets, largely physical endowments, and leveraged her way to a kind of celebrityhood through luck, determination and an apparent lack of any sense of dignity. She became an aggressively blowsy focus of titillated interest, a gold-plated skank because of her self-exploitive outrageousness in our densely interknit, mediacratic capitalism. (Recall how close we came to being subjected to OJ’s cynically, coyly disclaimed murder “confession” before News Corporation Baron-in-Chief Rupert Murdoch got cold feet.)

Over and over again the coverage of Smith’s demise at 39 has been observing that she was “famous for being famous,” which isn’t quite true. She was famous for her inveterately vulgar moxie and all-too-obviously calculating personality and major screw-ups. She was quite a show.

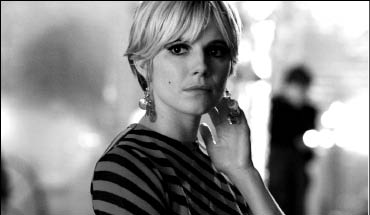

Poor Edie never had Smith’s resolute self-regard or, in the 1960s prehistory of the infotainment era, her options, despite her family’s wealth. As George Hickenlooper’s awkwardly moralistic movie has it, she did want some of what Smith got. “I think everyone wants to be famous,” Edie (Sienna Miller) says early in her career as a Warhol girl. Later, after the movie’s Warhol (Guy Pearce) has used, abused and abandoned her, an out-of-control Edie confronts the artist with complaints of the ruination he and the movies he made of her have caused. “Oh no,” Warhol purrs lethally. “They made you famous. That’s what you wanted.”

The movie never tries for any insight more telling or interesting than that. It’s told as an extended flashback, narrated by Edie as she relates her life and woes to an unseen therapist in Santa Barbara in 1970. She remembers herself as a sweetly naïve painting student at the “Cambridge School of Art” in Massachusetts, getting ready to decamp to New York where the creative action is in 1964. And where she hooks up with Warhol’s Factory crowd of film techies, art-production crew and assorted posturing, backbiting toadies.

As Edie becomes Warhol’s latest tawdry but glorified human obsession—at one point he says he feels something “very close to a kind of love”—and then plummets to being a druggy demimondaine, the movie presents her with an escape option. Hayden Christensen appears as the not-Dylan, a bike-riding folk singer who makes love to her and tries to pry her from the parasitic Warhol.

In the movie’s dubious version, Warhol reacted with coldly jealous resentment because of this relationship, although there’s little or no evidence she ever entered into one with Bob Dylan. Christensen’s unnamed, prettier and sweeter Dylan stand-in is explained by the real one’s threat to sue if his name or work was used (so we get Tim Hardin’s singing on the soundtrack instead).

Pearce’s Warhol is a frightening, passive-aggressive, vulturous, voyeuristic figure. The real Warhol may have been rather less than a sterling character, personally or aesthetically, but the movie’s caricature seems drawn mainly to advance its tabloid concept of Edie’s victimhood.

Hickenlooper tells this story with little adeptness or interesting detail. The movie is both didactic and sketchy. At one junction, fashion fascist and editor Diana Vreeland (Ileana Douglas) briefly appears without any real preparation or explanation.

Judging by the snippets of testimony by real people (including the late George Plimpton) at the movie’s end, the actual Edie was a more complex, talented and sometimes exasperating woman. The film needed someone else for its poor-little-rich-girl, gossip-column tragedy.

It’s a cheesy cautionary tale without much meaning. Factory Girl wants to cluck its tongue in disapproval, while it leers at the depravity it depicts.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n7: It's Mardi Gras Time! (2/15/07) > Film Reviews > Fame! (But Will They Remember Her Name?): Factory Girl This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue