Next story: The $26 Billion Question

Unity Force

by Geoff Kelly

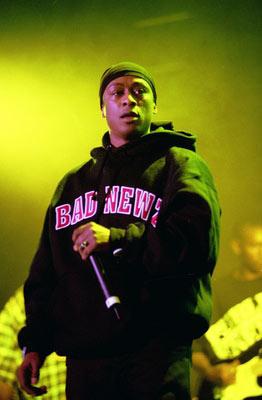

Public Enemy’s Professor Griff comes to Buffalo next week to lecture at the Freedom Film Festival

It’s been a cruel winter for Professor Griff: Last month a gas leak caused his house and studio in Atlanta to burn down. He and his family lost everything—clothes and valuables, book and record collections, lectures, studio equipment, the artifacts and memorabilia collected over the course of a career that reaches back more than 20 years.

Griff’s most famous role in that long career is minister of communications for Public Enemy, the pioneering hip-hop revolutionaries fronted by his childhood friend, Chuck D. But Griff (born Richard Griffin) has made his own name in the world as well, separate from but always in pursuit of the same agenda that drove Public Enemy: empowering black people, countering media dissembling, fighting the powers that be.

Griff comes to town next Thursday and Friday to deliver a lecture and screen the documentary he helped to make last year, Turn Off Channel Zero, which deals with the African-American stereotypes that populate the dominant American media. The film is part of Morningstar Promotion’s Freedom Film Festival, which takes place March 21 & 22 at the Screening Room (in the Northtown Plaza, 3131 Sheridan Drive). Other filmmakers include Doug Ruffin, Jr. and Karima Amin of Prisoners Are People Too, Kameran Woods and Andrew P. Mitchell. (The program runs 6-10pm both days, and Griff’s lecture is on Friday evening; check myspace.com/morningstarpromotions for more details.)

Professor Griff took time this week to talk to Artvoice about Turn Off Channel Zero, among other things:

Artvoice: How did you become involved with Turn Off Channel Zero?

Griff: Opio Sokoni was at the Black Holocaust Conference in D.C., and listening to all the speakers speak, it came to him that in order for us to balance this all out and to produce the next group of black leaders that are going to come up and speak on behalf of black people, young black students need to see strong black men.

And we’re just not seeing this. When we went to go find them, the majority of them had been bought off by this government, co-opted. They don’t really speak black, they don’t speak for black people. This is a problem, because we don’t see ourselves in the educational system. I mean, when you start talking about Little Black Sambo and Ten Little Niggers—these were books that were being used to educate black people. It’s not healthy. We could not find a strong black man.

And then the whole aspect of the effeminization of the African male. It’s ridiculous: Every strong black male figure that goes to Hollywood has to put on a dress, with the exception of Dave Chappelle and Denzel Washington. Dave Chappelle turned down $50 million, just to say, “No, I’m not doing it,” and we don’t know what Denzel Washington turned down. But you can’t find too many black men in Hollywood that didn’t put on the dress.

AV: So you’ve made this film, to talk about and expose that.

Griff: Yeah, we’ve brought it to the forefront. Being that hip-hop was so prevalent with young people, we tried to balance it out, and say, “Where are the strong black male images in hip-hop?” It was very, very difficult to find them.?

AV: In regard to the perpetuation of old stereotypes and the creation of new ones, how have things changed in that regard since you and Public Enemy first came onto the scene? Do you think the atmosphere is better or worse?

Griff: I think there was a period of rise and fall, of hills and valleys. I think when Public Enemy, when we were at our peak, I think we had raised the consciousness level of the people to the point where those who were playing this kind of trickery and this kind of game had to go back and reassess some of their strategy.

And they did! They just started outright paying people large sums of money to do the madness that they do: i.e. Flavor of Love; i.e. gangsta rap; i.e. Snoop Dogg. You understand what I’m saying? And now we no longer look at it like a badge of shame. We look at it as a badge of honor. It’s cool to be dumb and ignorant.

AV: At the height of Public Enemy’s popularity, there were other African-American musical acts and filmmakers who were not being socially conscious, who were not contributing to a revolution or cause. Is that okay? Does every African-American artist have to be socially conscious?

Griff: Oh, absolutely not. There are beautiful brothers and sisters, Doug E. Fresh is one of them who I’m close friends with. He’s the greatest entertainer in hip-hop. Does he have to be socially conscious and politically aware, outside of the context of hip-hop? I would think so. The community and our culture need to hold him accountable for some of the things he says, because he has influence over the people, inside his music. Can we have fun, just have fun? Can you and I hang out this Saturday and just have fun, without discussing a whole lot politically? Yes. We need that, because we need the balance.

But now let’s look at the scales, how they’re lopsided. Ninety-nine point nine percent of the artists that entertain us, and black people in movies, just disrespect black people blatantly. And disrespect themselves, and that’s sad. No other people on the planet will allow that. Not Indians, from India; they have too much pride. Japanese, Chinese, Jewish Americans…no one will allow that. No one has 99.9 percent of their artists making records and doing things in films that disrespect their people.

AV: So where do black people today find positive images, or find images at least that aren’t destructive?

Griff: I think we need a roadmap. You know how you go to Hollywood and you get those roadmaps to the stars? We need to develop a roadmap, because it is truly, truly, truly sad. It’s almost at a point where—

AV: Whose houses are on that map? Wesley Snipes? Is his house on the map?

Griff: Aw, you’re out of your mind. You could do a history of his films—wow. That dude dressed up as a woman? Wow. That’s critical. But, no. I think we would have to stop by Barack Obama’s house first.

AV: What do you think about Obama’s public image? What is the image that he’s projecting to white and black audiences?

Griff: To young people, he is giving a glossy image of presenting himself, or being presented by the people that control him, as the next Kennedy, the next Dr. King, you know. That’s the way he is being presented and propped up. Personally speaking, I think he’s connected to the bluebloods, and you know if you have that bloodline you’re not going to be the president of the United States of America. We know that. We know how many of them were related to one another. We know the blueblood line, we know the secret society, because it’s our people. We know this information because it’s out there. It’s no secret now. It’s not about what you know, whether or not you’re the best man or woman for the job. We know who you have to be connected to, in order to preserve this status quo, so to speak.

The reality of it when it comes to young people, especially black people, seeing a black man running for the highest office in the land, it just swells their chests for some reason with pride. Just trying to see us through another four or five years…It’s a false hope, but nonetheless it’s still hope.

AV: Why do you say a false hope?

Griff: Simply because you and I both know the day they say that he’s the President of the United States, you know he’s on the list for assassination. You know this. Once they open up those files in the back room…once he utters the fact that he might sign into law the reparations bill, to pay black people back…

AV: You think Barack Obama’s going to do that?

Griff: Hell, no. You know that. But the thought of it, you understand? I heard on the news the other day that the white conservatives are talking about, “It’s going to be a problem because his middle name is ‘Hussein,’ and al Qaeda’s actually going to think it’s a victory for them.” Which is wildly crazy, it’s insane for them to even think that they’re going to win the guy as president. Because he’s president on face value, but the policies are not necessarily going to change. The presidency is a public seat; there’s someone else pulling those strings. We know that. Can we put this in the paper, in the article? Probably not. [He laughs.] You’ve got to keep your job.

AV: You’d be surprised what we can put in our paper.

Griff: Oh, I hear you.

AV: We can get away with a lot.

Griff: Isn’t that something, that you and I have to use that language? “We can get away with a lot”? Ain’t that something?

AV: Well, it used to be that you had to be worried about whatever vehicle it was you used to communicate; you had to worry about keeping it alive, which meant making compromises. Do you feel that technology has changed your ability to communicate, to reach out, to be an activist?

Griff: It’s a blessing and a curse. It’s a blessing simply because right now you and I can have this conversation, and in the next five minutes we can have it out throughout the world. Literally. But false information can be put out about you and I—that we’re gay, that we’re secretly lovers—that can also go out, and it can also damage your career and mine. So it’s a blessing and a curse. We can get information out instantaneously, but who we reach and how we reach them is [determined by] the medium that someone else set up, as far as Google, Yahoo, Gmail, Hotmail, all this other stuff. We have to go through their medium.

But then again, who can afford, who actually has access to computers? And once the average 17-, 18-year-old logs in, where are they going? What chat rooms, what communities, what blogs? So it’s still a challenge; we still have to find what’s attractive to them. That’s our job.

You see, hip-hop had no script; it was organic. It went out, and for the most part white people didn’t know what the hell we were talking about. They didn’t know “a-hip, a-hop, the hippy, the hippy to the hop,” they didn’t know what that was. Once we started validating, and they started validating and packaging hip-hop, then it became the curse. We sold out to the highest bidder.

AV: So where is that sort of cultural secret now? Where is that thing that only black people have now? Is there something like that, like hip-hop as it was back then?

Griff: Well, my thing is, even now, when we discuss certain things, in the way we discuss them, and the trends and the fashion and the talk and the swagger, and what we listen to and how we listen to it and how we interact with it—I think that being the people that we are, we invite every other people in, every other culture in. And it’s critical because in any given black movement, in any given black trend, there’s only X number of white people that come in. But with hip-hop, oh my God…

And we don’t mind. But the curse is that they co-opted it, corrupted it, turned it into something else. Dumbed it down for mass consumption.

AV: Is there any hope for hip-hop out there? Are there any artists or any groups out there that are doing something that you can respect? Some new direction?

Griff: Oh, you and I know there’s nothing new under the sun. But I love Lupe Fiasco and what he’s doing. Immortal Technique, NY Oil, Jean Grae…these artists will probably never get the Grammys and the awards like Lupe Fiasco received, but these artists are bubbling under. They’re really moving underground. There still is an underground—you have to really submerge extra deep, because this stuff that’s considered underground is not really underground; it’s really pop. Underground has no rules, no holds barred. You just go for it.

AV: And that’s where music changes.

Griff: Exactly, exactly. Now you can’t differentiate between what they’re calling underground and what’s above the ground. It’s like, “That sounds like something that should be on the radio.” That’s not cool; we ain’t checking for that. I was in the club the other night and they were playing some stuff and I was like “Who was that?” and they were like, “These artists don’t even want you to know who they are.” The guy just made this in his bedroom two weeks ago, and that’s the kind of stuff you see on YouTube.

But you’re also seeing 16-, 18-year-old girls taking off their clothes on YouTube. And it’s like, wow, this is critical. You have to guard your children from it, at the same time you’ve got to be on there to get the information. Blessing and a curse.

AV: So, what’s next for you? What are you working on now, besides a new house?

Griff: [He laughs.] I’m glad we can kind of chuckle about it.

AV: I’m sorry to laugh...

Griff: No, I need to. I need a laugh. I am trying to finish my book, The Psychological Covert War on Hip-Hop.

AV: Tell me about that.

Griff: The whole idea is to try to uncover this covert war that’s going on in this genre of music, of black music that we call hip-hop. And there is a war going on. For example, in the book The First Millennium Edition of the American Directory of Certified Uncle Toms, on page 236 it talks about the nefarious negroization of hip-hop, rap music…[they] created this certain tone that they call the Twelve Atonal Tones, [which] they’ve put among hip-hop and actually made this thing, created this thing called gangsta rap. Put it among our people and paid gangsta rappers large sums of money to carry these frequencies, this tone, throughout hip-hop. We see the end result, and it worked. They created gangsta rap to neutralize conscious hip-hop, i.e., created NWA to neutralize Public Enemy.

If I ran down a list of all the young white independent record company owners who took instructions from their forebears that said, “We have to keep this thing going, and get paid from it. They want to kill themselves, dope and crack and sing about it, then we’ll profit off of it.” It’s a fascinating story.

But we were the first targets; you have to understand that. Starting with Public Enemy.

AV: Were you aware of that at the time?

Griff: No, not at all. There’s a gentleman who wrote a book called Hip-Hop Decoded, and his name is The Black Dot, and it really opened my eyes. And then Congresswoman Cynthia McKinney pointed things out to me that were just mindblowing…[she] gave me documents showing that we were under surveillance, that black rap and hip-hop artists were under surveillance. I went to go look into it, thinking that, okay, I’ll find one article, maybe two. I started uncovering document after document after document, not only on myself and Public Enemy but just the average artists—hell, Chingy. Chingy? I’m like, he’s the cutest little guy in music, man. What is he threatening? You know if they’ve got a file on his ass, you know what they have on me.

Seriously—they don’t want strong black intelligent men in the industry, that’s not going to sell out, that’s actually going to do right by the people. Some white people look at this, they say, “Well, if he’s doing right and making a sacrifice by his people, we ain’t got nothing to worry about.” But there are some segments of the human family that’s not looking at it like that. They looking at this thing like, “Griff is a threat. Public Enemy is a threat. We can’t have too many Public Enemy groups out there like that.”

AV: That was the thing about Public Enemy: It didn’t end after a concert, or after a CD comes out. You guys are were lecturing, you were going out in the community—

Griff: Right, right.

AV: You’re like any activist group. Who does that now?

Griff: Talib Kweli, Mos Def. On a different level, you know—it’s not the same tenacity. They don’t do it with the same dignity and the same passion. They do Cadillac commercials and beer commercials, which is not going to get it; that’s not going to get it.

AV: That’s not a radical message, for sure.

Griff: Desperate times call for desperate measures. One breath you’re telling kids to just do this, that or the other, but you’re profiting off of their misery by making a beer commercial. That’s counterproductive. It’s counterrevolutionary.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v7n11: Public Enemy's Professor Griff (3/13/08) > Unity Force This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue