Who is James A. Williams?

by Jamie Moses

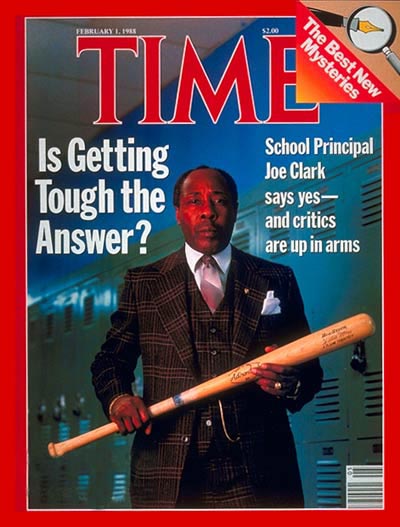

Twenty years ago, when James A. Williams was appointed deputy superintendent of the Dayton Public Schools, Time magazine ran a cover story about a bat-wielding high school principal from Patterson, New Jersey, named Joe Clark and a school board that was threatening to fire him. Clark, a “take charge” kind of guy, had created a controversy because he was determined to clean up a troubled Eastside High the way Wyatt Earp cleaned up Tombstone or George W. Bush was going to clean up the Middle East: Throw out all the bad guys and make everyone one behave.

Clark was full of pithy aphorisms like, “If you can conceive it, you can believe, and you can achieve it.” He also had a healthy ego, “In this building,” he told Time magazine, “everything emanates and ultimates from me. Nothing happens without me.”

Clark did clean up Eastside High. He roamed the halls with his bat and tossed out the bad guys, mandated a “walk-to-the-right and keep moving” rule, banned hats, gang colors, and created a dress code. He made unilateral decisions to expel entire groups of kids, established harsh late-to-school policies and fired, or encouraged to leave, any teacher who disagreed with his vision; a hundred teachers fled during his six-year tenure; but to hell with the teachers, this about the kids, right?

Clark’s law-and-order vision was irresistibly appealing to folks fed up with what appeared to them an out-of-control generation of urban students. President Ronald Reagan commended him, he toured the talk-show circuit and Warner Brothers paid him for rights to make a movie of his life. Unfortunately, despite the misleading movie, student scores didn’t improve; the students were still failing at reading and math.

James A. Williams, whose mother, wife, and three sisters are all teachers, has a lot in common with Joe Clark. They both have intimidating personalities, and, before going to Dayton, Ohio, Williams did pretty much the same thing at Cardozo High School in Washington, DC that Clark did at Eastside High. As a result, like Clark, Williams has a bewitching appeal to community leaders looking for a person who promises to come in and shake things up, and to parents who are desperate for someone who promises to keep their children off the streets and teach them to learn. Yet, both have failed to realize much student improvement.

Both also have a knack for feeding the press a running supply of good quotes. The Buffalo News is littered with the dramatic, dime-store passion of James A. Williams: “These kids are suffering. They’re dying intellectually. It’s very painful.” “We’ve got to stop the bleeding.”

Dayton: Ready or not, here I am!

In 1991, when Dayton’s superintendent of schools took another job, the Dayton Board of Education decided their replacement would either be James A. Williams, who had a reputation for being brash and aggressive, or Assistant Superintendent Jerrie McGill, a friendly consensus maker who oversaw planning. They chose Williams, who moved up from his $75,000 salary as deputy superintendent at Cardozo to $112,482 plus benefits as Dayton’s superintendent.

The Dayton News reported that Williams was visibly moved in accepting the position: “Leading a school district has been my dream. I will take a 20-year contract if it is offered.”

Williams moved quickly to make changes, proposing a magnet-choice system and leading a levy campaign to raise funds. He also suggested compassionate but vague plans for measures like finding volunteers to offer parenting courses on life skills: “It’s going to be simple things. How to go to the bathroom appropriately. How to eat appropriately. How to say, ‘Excuse me.’”

But his brusque style and autocratic decision-making created enemies quickly. Without warning, Williams simply eliminated an effective in-school suspension program for fighting or disruptive children and transferred the paraprofessionals who staffed the program in 36 elementary schools to other jobs. One unhappy board member said, “Dr. Williams did this before we had an opportunity to discuss it. This should have been delayed until Dr. Williams presented an alternative plan.”

Williams told board members he wanted principals to come up with more creative ways to discipline students. They didn’t. Principals were upset and the aides union was upset.

“If we don’t have in-school suspension, kids who are disruptive are going to be expelled, and where will they go?” said one principal. “Many of these children’s parents are working. The child, unattended at home, will probably wind up on the streets.”

The teachers strike

By 1993, teachers registered a no-confidence vote in Williams’ leadership and began a 16-day strike. The teachers’ blamed Williams’ obstinacy for precipitating the strike.

With no teachers, students were shuffled to cafeterias and auditoriums in an atmosphere of confusion. Many just walked out after seeing the chaos.

“It’s horrible in there,” one 17-year-old junior from Meadowdale High School told the Dayton News. “Everybody’s jumping around, screaming, yelling, throwing things. What kind of education am I going to get?”

At Stivers Middle School there were 10 false fire alarms, frequent fights, and students throwing eggs in the auditorium. Many students called home for permission to leave school.

“It’s crazy in there. It’s dangerous,” one student told the Dayton News.

The chaos played out across the entire school system. Williams only acknowledged some “problems in the daily routine.” About 184 substitute teachers worked the first day of the strike, and about 105 security guards monitored picket lines. The security service cost the district $27,000 a day, including food, lodging, and travel.

The union’s issues were Williams’ demand that teacher raises be linked to student test scores, voluntary transfers by seniority, health insurance, and retroactive pay.

“You have no control over how your kids do on tests if they don’t come to school,” said Margaret Peters, a teacher for 30 years. “They are asking us to solve problems that students did not have when I graduated in 1954—crack houses and kids coming to school full of drugs.”

Health insurance was the primary sticking point. “”If they could remove ‘cap’ from this discussion, this could be settled,” said a strike coordinator.

The school board proposed a “cap” on what it would pay toward health coverage and projected only a 14 percent increase in health cost, while the national average was a 25 percent increase. Teachers voted by more than four to one to reject what the school board called its final offer.

“We’ve made our last offer, but we are willing to go back to the table,” Williams said.

During the strike Williams laughed about T-shirts the union printed as fundraiser for their scholarship program. The shirt featured a caricature of him as a shark swallowing a teacher and read, “I survived JAWs.” He made rounds of the schools “as if he had just been elected mayor, hugging kids and chatting with principals.” But many “parents were on the picket line with the teachers and were in a fighting mood, demanding to know when teachers would be back in the classrooms,” the Dayton News reported.

Teachers are committed to the students, “but they don’t see the big picture from where I sit,” Williams said. That comment annoyed one strike coordinator, who’d taught through the tenure of several past superintendents. “Dayton is not just a line on my resume,” she said. “Superintendents come in with their agendas that we’re supposed to get excited about and then they move on. We have to succeed in spite of that.”

“I’m not interested in any other superintendency in the country,” said Williams. “I plan to retire here.”

In spite of the bedlam in the school system that the strike created, the bankers and the business segment of the community staunchly supported Williams. The strike lasted for 16 days, with food-service workers, custodians, and paraprofessionals filling in for the certified teachers. Of the 1,900 teachers in the system, only 169 crossed the picket line.

The ideas man

In spite of the fact that he was secretly putting his resume out and would soon be trying to land the job of superintendent in Atlanta, with the Dayton teacher’s union strike behind him, Williams showed great enthusiasm for the new school year ahead. At 11 Dayton schools he introduced what he believed would be the academic fashion rage of the future, uniforms, and hired a new deputy superintendent because, he said, “I want to spend more time on long-range planning, goal-setting.” He arranged for Medicaid to pay for students to get a physical examination by district doctors every year, which was great. But then he introduced a plan to turn students away the door of the school if they arrived more than 45 minutes late. This, he said, would encourage them to get to school on time. Instead it gave them an excuse to not to be in school at all. “It’s pitiful,” said one parent. “They enjoy being sent home.” Another parent of three said if his kids are turned away they would just spend the day on the streets; he said he would prefer in-school detention, but then Williams had eliminated that program the year before.

Truancy was a problem; Dayton had a lower attendance rate than any other district in the state. Williams held a press conference with Dayton’s chief of police to announce truancy patrols. Cops would sweep through neighborhoods and pick up students who should be in school. This must have pleased the school board, because they immediately voted to give Williams a four percent increase in his salary to $108,008.

Williams next proposal was a restructuring of the districts 1976 desegregation plan, a massive building program that involved closing nine schools, building new schools, and consolidating schools. It had a price tag of $400 million and Williams planned to ask the state to pay. When Ohio Governor George Voinovich was asked if the state would pay for the project his answer was short: “No.”

“It would be hard for us to find the money,” said state Rep. Tom Roberts, D-Dayton. “It’s hard to find any money.”

In a series of “town hall” meetings and television and radio appearances, Williams embarked on a campaign to get public support before making a formal request for the $400 million. He also suggested that if the state didn’t give him the money, he would ask the school board to sue the state for the money.

A candidate for all seasons

Williams didn’t get that Atlanta job in 1994. But in February of 1997, amidst his $400 million campaign for the Dayton district, Williams became one of three top candidates for a job in Durham, South Carolina. There were reports of racial tension in the Durham selection process, but Williams said he was unconcerned about the controversy, because he was now focused on how he could improve Durham schools by bringing people together.

“The mark of a good leader is to rise above those issues and try to do what’s right for children,” he said.

Williams didn’t get the job. Two weeks later, Ohio state auditor Jim Petro demanded Williams repay $39,000 to Wright State University because he couldn’t document services he was paid to perform. That amount was in addition to $8,000 he’d already repaid two years earlier for teaching duties he also did not perform.

This was immediately followed by a school bus crisis that finally boiled over after months of children being routinely left stranded waiting for buses for as long as two hours. A daily average of 41 bus drivers were calling in sick, and there was high employee turnover and absenteeism. The union laid the blame squarely at the feet of management for understaffing, low wages, and lack of discipline.

The school bus crisis was followed by lousy test results in state tests. To shift the conversation, Williams proposed introducing “Twilight School,” which would operate between four and eight o’clock, and would be an alternative to suspending disruptive kids. “Whatever the cost, we need to find the money,” said Williams.

Parents responded that the in-school detention Williams had eliminated was a better idea.

By the following month Twilight Schools had fallen off the radar screen and now Williams was on a drive to convert three Dayton elementary schools and two middle schools to charter schools. Williams spent the entire year in secretive planning sessions, with teachers and parents trying to extract information. He outright misled everyone about which schools would be converted and who would run the schools. A private company was awarded the contract. The next several months were filled by fights with the unions and a whole tangle of intrigue: Suffice it to say that Dayton has more charter schools than nearly any city in the nation.

One interesting occurrence during the charter schools struggle was a letter written and singed by Jessie O. Gooding, Dayton branch president of the NAACP. The letter was critical of Williams and his relentless flood of half-baked “innovations.” “…each year,” wrote Gooding, “ a new ‘innovation’ is proposed by Williams without careful thought regarding the impact on instructing the students nor a cost-benefit analysis.”

The charter schools were approved and immediately began draining money from the district. Then, in April 1998, the percentage of high school seniors who passed the 12th-grade proficiency test dropped in all but one academic area. Bad news. In May, Williams signed Coca-Cola to a $2 million exclusive pouring rights contract. Good news. Unfortunately, that was offset in June by a $3 million state funding cut because of projected loss of student enrollment.

Williams complained he had no control over the dropout rate, 43 percent, and proposed that an alternative boarding school could be a solution. “We need to take kids away from their environment,” Williams said. “We might need to have them 24 hours a day.”

To some parents, that sounded like jailing their children so Williams could get his state money.

Williams claimed he had brought financial discipline to the district, indicating that the district had balanced budgets for seven straight years. However, in August 1998, a special state audit concluded that Dayton Schools made $250,553 in improper payments to a consulting firm tied to the same company that had been hiring Williams for the “work” for which he already had been directed to repay $39,000 to Wright State University. The owners of that firm went to jail. Nevertheless, that same month the board extended Williams’ contract, but this time by only one year, and included accountability measures, which did not sit well with him.

But Williams was job-hunting by that point anyway. In January 1999, Williams was announced as a finalist for the top job in Dallas, which shocked the Dayton board. In February, Dallas announced he was pretty much their choice. Only, unlike Buffalo, before they signed the dotted line, the board wanted to see the man in action. The entire board flew to Dayton. They met with Williams, they looked at his schools, they talked to people. They flew back to Dallas and they didn’t hire him. Having seen Williams’ handiwork, the Dallas board of education opened a new search.

Immediately afterward it was announced that Williams was a finalist for the superintendent’s job in Hartford, Connecticut. That news also caught Dayton board members by surprise, though you’d think they would have realized by then that Williams was trying to run out on them. “First time I ever heard this one,” Dayton school board vice president Ricky Boyd said of Hartford. But, like Atlanta and Dallas, Hartford also decided that they didn’t want Williams.

Oh my, what’s this?

It soon became clear why Williams was so anxious to leave Dayton. In May 1999, the budget that Williams said was balanced was suddenly looking at a deficit of $19 million; by Ohio law the district’s budget had to be balanced by June 30. In a panic, the district canceled all non-essential purchases and sought to borrow money, transfer funds, and put off financial obligations to make it through the end of the school year. School officials scrambled to figure out how they’d spent $213 million instead of the $181 million budgeted in June 1998. A city legislator proposed the Dayton City Commission take control of the school system.

The district had hired a new budget director, Jan Schultz, in February, and she discovered the shortfall immediately after taking over. She told Williams about it in March. But Williams kept the problem quiet, according to records and interviews with district administrators. Meanwhile, he was trying to bail out of Dayton and leave them to discover the mess after he had a new job elsewhere.

Schultz said she didn’t know how the looming deficit escaped school officials’ notice.

State auditor Jim Petro slammed the district’s financial planning, record keeping, and business practices. County auditor A.J. Wagner said, “We’ve never encountered a surprise like this,” expressing disbelief that Dayton schools did not have a system of checks and balances to catch budget mistakes.

School board members told the Dayton News that Superintendent Williams had been continually assuring them since January that financial problems were under control.

“We were being given wrong answers or no answers,” said Ricky Boyd, board vice president. But board member Nancy Brown said she never trusted Williams’ assurances.

“We got hesitant answers from Treasurer Ken Goff, so I suspected that everything was not right,” Brown said. At the time, she told the Dayton News that she “would not be unhappy” if Williams were to find another job.”

Williams tried to blame it all on his staff. “I’m not taking this beating,” he said.

But state auditor Petro determined that Williams was spending in excess of budgeted revenues every year: “Their budgeted revenues grossly exceed their actual revenue and they’ve been running a cash deficit [expenditures exceeding revenues] in excess of $5.5 million annually.”

Petro said the district masked the problems by delaying payment on bills incurred in one fiscal year until the next.

Budget director Jan Shultz said the district also drew on a cash reserve fund until it was completely depleted. Schultz said the problem became evident to her soon after she arrived in mid-February and analyzed trends for the past seven years. She saw that the district’s fund balance—resources left after all obligations are accounted for—had declined annually since 1994 and was on course to be $114 million in the red by 2002.

Williams wouldn’t say when he knew about the deficit. He couldn’t explain why he never made the staff cuts he promised to the board, nor why he failed to notice that spending was 19.02 percent over budget. After failing to convincingly blame anyone on his staff, all he said was “I take full responsibility.”

Petro told the Dayton News, “The recipe for sound financial performance is simple: use conservative estimates of revenue, budget conservatively and spend less than is budgeted. Those three things will keep your house in order. James Williams has done everything wrong, rather than everything right.”

What me worry?

On May 31, 1999, a few days after the financial bomb dropped on the school district, the Dayton News wrote:

James Williams leans back in his office chair, smiling and joking with reporters just a few hours after listening to a Dayton board of education member publicly call for him to be fired.

Williams assured all within earshot that “I’ll be here, I’ll be here a while.”

Board member Nellie Terrell’s suggestion during a board meeting to terminate the superintendent’s contract drew a chuckle from Williams, who had left his seat and was standing to prepare a budget presentation. He was paid, at that time, $114,394 a year in base salary, though his annual compensation, including an annuity, medical and life insurance, car allowance and other benefits exceeded $200,000 a year.

Williams attends last board meeting

In July 1999, Williams attended his last board of education meeting as Dayton Public Schools superintendent. He spent most of the meeting guiding the board through items requiring its attention during the upcoming school year. The last item of the meeting spelled the end of Williams’ tenure: The board approved a resolution 7-0 to authorize a search for Williams’ permanent replacement.

Williams left a closed-door meeting that followed without indicating his future plans.

“He’s pretty much destroyed Dayton schools and their credibility in the community,” said Lori Crank, parent of a former E.J. Brown Elementary School sixth grader.

Crank said her daughter’s bus regularly passed her by or left her behind at school, but she got no help from school officials. When she called Williams, she was told he didn’t talk to parents. Crank finally decided to move.

“He doesn’t care about kids at all,” she said.

Next Week: ARE LUNATICS RUNNING THE ASYLUM… and the Buffalo Public Schools too?

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v7n20: Dig The Tomato Man (5/15/08) > Who is James A. Williams? This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue