Next story: Beavis and Butthead's Father Runs for President

Eight Days in Guantanamo

by Julia Hall

A Buffalonian observes the trial of Salim Hamdan and the degradation of American justice

Osama bin Laden’s driver, Salim Hamdan, had been detained at Guantánamo Bay for six and a half years when his trial by military commission commenced on July 21, 2008. It would be the first military commission convened by the US government since the Nuremberg trials of 1945-1949—and, as such, a historic event. Along with a handful of others, my organization, Human Rights Watch, was granted permission by the Department of Defense to monitor L’Affaire Hamdan. As the organization’s anointed monitor, I traveled from my home in Buffalo to Guantánamo Bay: a trip down the East Coast, extended a few hours by the need to fly around Cuban airspace, then on to the infamous naval base whose detention center houses inmates who were held in secret prisons abroad and many who were ill-treated or tortured, representing one of the worst excesses of the Bush administration’s “global war on terror.”

I was not impressed by the notion of historic import. Hamdan’s trial was the culmination of a period in US history marked by the profound tragedy of 9/11, but the victims of that crime against humanity would not see accountability with a Hamdan conviction. The military commission’s unfair rules—and the physical and psychological abuse Hamdan suffered in Afghanistan and at Gitmo—doomed it from the start. But the panel of Pentagon-selected military officers who eventually convicted Hamdan on August 6 for providing material support to al-Qaeda (and acquitted him on what were more serious conspiracy charges) must have understood how the deck was stacked against bin Laden’s chauffeur: Hamdan got five and a half years, but no one, not the lowly driver or al-Qaeda’s victims, got real justice.

As senior legal counsel in the Terrorism and Counterterrorism Program at Human Rights Watch, where I have worked since graduating from the University at Buffalo Law School in 1996, I usually cover counterterrorism and human rights in Europe and Central Asia. In the last few years, my work has taken me from a home office in my Allentown neighborhood to European capitals from Amsterdam to Stockholm. I’ve gone to Moscow on behalf of Uzbek refugees, to Istanbul on behalf of Kurds, and to Berlin, Brussels, Dublin, Geneva, and London to call on European leaders to honor their human rights commitments while fighting terrorism. The Buffalo-Europe axis is my regular beat.

Guantánamo Bay’s tentacles, however, have impressive reach. Researching “extraordinary renditions” from and through Europe as early as 2002, I subsequently discovered that a number of persons who had been apprehended by CIA operatives and illegally transferred to places like Jordan and Egypt,+ where they were interrogated and tortured, ended up at Guantánamo Bay. More recently, Human Rights Watch has taken up the cases of several prisoners who have been cleared for release from Guantánamo, but can’t be sent home because they risk torture if returned to countries like Uzbekistan, China, and Algeria. Because the US government, supported by the Congress, has made it clear that no detainee, no matter how mistaken his capture and imprisonment, will be allowed to enter the US, we have been talking with European governments about “stepping up to the plate” and offering the men refuge. (That’s a tough sell.) In these matters, Guantánamo Bay is a European issue.

I did not have a desire to work on the US side of things when I was called up to observe Hamdan’s military commission. In retrospect, however, after spending eight days and an incredible amount of mental energy on Gitmo, I understand that no matter what aspect of Guantánamo Bay is under examination, a person can’t fully understand this off-shore prison project without going, seeing, and experiencing the now iconic legal black hole that the detention center and military commissions represent.

Camp Justice and the minders

The accommodations at Guantánamo for visitors from human rights and civil liberties organizations were fairly comfortable—that is, until I arrived. The base is divided into two parts—the leeward side and the windward side—by the two-and-a-half mile-wide Guantánamo Bay. I got from one side to the other as the sole passenger on a perky little Coast Guard boat called a Viper, accompanied by four armed national guardsmen who called me “Ma’am.” I suspect they thought that breakneck speed would scare me, but I grew up on Lake Erie and the Niagara River, with a love of boats and the water. The three trips out on the water during my stay were guilty pleasures.

The main base—including the prison camps we have never been able to visit, the courtrooms, the McDonald’s, Subway, and Starbucks—is on the windward side. The detainees’ lawyers and my other Human Rights Watch colleagues (who came down for pre-trial hearings) had always been lodged on the leeward side, in shared rooms at the quaintly named “combined bachelor quarters,” or CBQ. There was cable TV, phones, Internet access, kitchen facilities, maid service, and some noise about nighttime barbeques on the beach.

The email from the Department of Defense with information about my travel orders (which permitted me to travel to Cuba legally from the US mainland) informed that “significant” changes in accommodation had been made. Not only did I have the misfortune of traveling to the tropics in July, but also of being in the first “class” of trial monitors to be “accommodated” in army-issue tents, pitched in a tent city on the windward side in the ironically named Camp Justice. If nothing else, Camp Justice was convenient, located just down the hill from the courthouse where Hamdan’s trial would take place.

The tents (per the email, “kept very cold to keep rats and bugs out”) slept six with partial walls for some privacy, but as the only woman observer the first week of Hamdan’s trial, I had the whole place to myself (if you don’t count the dozens of admittedly harmless but annoying bugs, deviously immune to the hyper air conditioning). Toilets, partially curtained on the sides but with no front doors, and communal showers were in separate tents. The TV did not work, the refrigerator and microwave did. Internet access was up for one day and then down for the next two, and maid service was self-executed.

Needless to say, my discomfort was nothing given the conditions in which the detainees were held: unlawful indefinite detention, no due process, torture and ill-treatment, and, for a very few of the 265 detainees, soon-to-be-unfair trials. Put into proper perspective the tent was downright luxurious.

The more insidious problem came with the Pentagon’s order that observers be escorted everywhere on the windward side when not in their tents. One “minder” was assigned for daytime duty, another for evening. The four observers in my pack thus had to agree on where and when to go to breakfast, lunch, and dinner, when to work, what recreational activities (such as they were) to engage in, and when to call it a night. Fellow observers—from the ACLU, Amnesty International, and Human Rights First—were courteous and accommodating, but Big Brother surveillance of this sort could get on anyone’s nerves. I breathed a sigh of relief when the outing to the go-cart track, managed through the Morale, Welfare and Recreation division on the island, fell through due to lack of time. And I became extremely irritated when warned by a soldier that I needed to be escorted in order to use the portable latrines 50 yards from the courthouse door.

It’s important to say that our military minders, men and women from the Joint Visitors Bureau on the base, were unfailingly polite and helpful. In any other setting, they would have appeared as cheerful cruise directors, at the ready to assist. (I wish I could say more about my interactions with them, but my discretion will help avoid getting them into trouble for the small kindnesses they eked out for us.)

The sole activity I was permitted to do alone outdoors was run every morning on a designated path around the bay. (I think the minders realized how absurd it was to let me run around the bay for an hour alone, but not to let me sit at the Starbucks and work without the full coterie of observers.) Sporting the required reflecting belt and an official ID badge, I faithfully set out at 5:45 every morning for that one hour of freedom. Sunrise on the island is spectacular. Rounding a bend on that first morning, I saw a huge American flag waving on a hill. Would whatever promise of respect for rights that many the world over normally associate with the American flag be delivered in Hamdan’s trial? By the second day of the trial, that query would be answered with a resounding “no.”

The new normal: Military Commissions Act of 2006

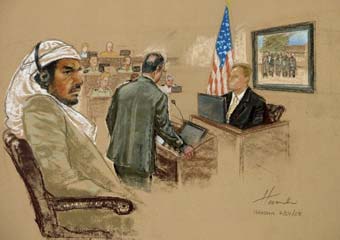

Judge Keith Allred, a Navy captain, bounded into the courtroom every morning in full black robes. The gallery sprung to its feet at the cry of “All rise!” upon his entry, and it was confirmed by others that he did indeed wink at Salim Hamdan every day as a ritual greeting. Much of the daily courtroom scene looked familiar: judge, jury, dark paneled courtroom, “Objection,” “Overruled.” But the differences were so distinct as to be surreal: an offshore prison camp for alleged terrorism suspects not far away, many of its inmates subjected to “enhanced interrogation techniques” amounting to torture, a jury of military officers in full dress handpicked by the Pentagon, and a set of rules that clearly violated due process. It would have been easy to be lulled by the normalcy of it all, if you didn’t know where to look for the blemishes. While one of the observers warned that we “shouldn’t drink the Kool-Aid,” I preferred chief defense counsel Colonel Steven David’s take: “Sure, it looks like a trial…from 20,000 feet.”

The key problem with the military commissions at Guantánamo Bay is with the law establishing them. In 2006 in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, the Supreme Court struck down the system of military commissions authorized by President George W. Bush in a November 2001 executive order. The court also found that the commissions’ procedures violated basic fair trial standards required by the Geneva Conventions of 1949, which it said mandated the humane treatment of all persons held by the United States in the “conflict with al Qaeda.” In response to Hamdan, the Bush administration pressed Congress to pass legislation that would have sharply limited the legal protections afforded detainees who were mistreated. Congress did just that by passing the Military Commissions Act of 2006 (MCA), which created military commissions little different from their discredited predecessors.

During Senate debate on the MCA, Senator Hillary Clinton pointed out that the MCA’s most insidious provision allowed the admission into evidence of statements extracted through cruel, inhuman, and degrading interrogation. She argued that the US “must stand for the rule of law before the world, especially when we are under stress and under threat. We must show that we uphold our most profound values. The rule of law cannot be comprised.” Clinton lost her challenge to the MCA, the act passed in October 2006, and Hamdan’s unfair trial proved her right.

My congressman, Brian Higgins, enjoys the dubious distinction of being the only Democrat in the New York Congressional delegation—House of Representatives and Senate—to have cast an “aye” vote for the Act.

Evidence of coerced interrogation

Watching the two Hamdan “capture videos” the second day of the trial was harrowing both for what they depicted and for the fact that they were admitted into evidence at all. The videos document Hamdan’s interrogations by US military personnel in Afghanistan right after he was taken into custody. In the grainy black-and-white film, the videos show Hamdan slumped on the floor, hooded and shackled, as he is badgered by his Arabic-speaking military interrogator in a dark room with one dim light bulb overhead. An armed soldier is behind Hamdan, the interrogator in front.

After removing the hood, the interrogator begins the questioning, only to be interrupted several times by Hamdan, who asks if he can change positions, move his legs, and rub his foot. There is a sickening sense that Hamdan, visibly scared, searching for the right words to appease the interrogator, is trying out ideas as they occur to him in an attempt to avoid more abuse. Apparently the prosecution introduced the tapes to show that Hamdan, who denied knowing Osama bin Laden in those first interrogations, was a liar and couldn’t be trusted. An odd strategy since Hamdan went on not only to admit in dozens of subsequent interviews that he did know bin Laden and had driven for him, but even escorted some of his interrogators to former al-Qaeda compounds and provided additional intelligence information of great value.

The defense, dubbed “Team Hamdan,” strenuously objected to the admission of these tapes as evidence. According to military commissions’ rules, evidence obtained through torture can’t be admitted. But the US government has defined torture so narrowly that it seems almost anything can be admitted into evidence as a product of “mere” coercion.

Although Judge Allred acknowledged in a ruling issued the day before trial that Hamdan was subjected to “various types of coercive treatment,” he overruled the objection to the tapes, saying that the rules allow the admission of coerced testimony if it is deemed “reliable” and in “the interests of justice.” Those tapes, he concluded, served the interest of justice and were allowed in. Never mind the coercion.

That first week of trial, both the prosecution and defense made veiled references to a May 2003 interrogation of Hamdan. Judge Allred had yet to make a decision about whether the prosecution could offer the fruits of that interrogation as evidence due to concerns about coercion. The government wanted to put Robert McFadden, a special agent with the Naval Criminal Investigative Service, on the stand to testify, claiming that McFadden could provide “clear and convincing evidence” that nothing elicited from that interrogation was coerced.

The judge eventually allowed the government to make its case the second week of trial. Human Rights Watch’s monitor for that second week reported that, without the jury present, McFadden—earnest, calm, like a cop out of central casting from Law and Order—described what he said was a cordial, friendly, and “free-flowing” conversation on May 17, 2003, in which Hamdan admitted that he had pledged bayat (an oath of loyalty) to Osama bin Laden and that he was carrying missiles to bin Laden when he was captured.

Team Hamdan challenged McFadden’s testimony, arguing that even though McFadden may not have used coercive techniques, Hamdan had been sexually harassed by a female interrogator who inappropriately touched him and subjected him to a program of sleep deprivation in the days prior to McFadden’s interrogation. (The defense provided documents showing this, but they were deemed classified and could not be discussed in open court.) The defense also pointed out that Hamdan had been interrogated by 40 other agents from 12 different agencies, and had not admitted pledging bayat to bin Laden to any of them.

The judge ruled in favor of the prosecution and allowed McFadden to testify. Unfortunately the public will never know Judge Allred’s reasoning. Four of the five pages of Allred’s written decision allowing McFadden’s testimony are entirely blacked out.

Staunch defenders of the military commission process will point to other statements that Judge Allred excluded from the trial, because they were coerced, to argue that the process was fair. But with some evidence admitted that was clearly obtained through coercion, those claims ring hollow.

Of ironies and surprises

The defense did its best throughout the trial to cast doubt on Hamdan’s role in al-Qaeda and on the fairness of the military commissions process. I have been doing counterterrorism work almost exclusively for the last five years and I was struck not only by the number of inconsistencies in the prosecution’s case, but by clear evidence of the governmental ineptitude.

Would the jury be surprised to learn that Hamdan’s boss, Abdullah Tabarak, in charge of bin Laden’s security detail, including all bodyguards and drivers, had himself been detained at Guantánamo Bay but was released and sent home to Morocco in 2004? Did they know that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of 9/11 currently in prison at Gitmo, called Hamdan a “bedouin” not fit “to plan or execute” outside operations (code for terrorist activities outside Afghanistan)? Were they disheartened by information they received in a closed session that Hamdan had begged interrogators not to rape his wife or kill his family, and that in the days when US forces were still on the hunt for Osama bin Laden and the other top al-Qaida leadership in Tora Bora, Hamdan made what was referred to as “a significant offer of cooperation,” which, the defense wondered, might have led the US to capture bin Laden himself? Were the jury members aware that Hamdan was prodded out of his Guantánamo prison bed in the middle of the night and interrogated by a US agency that could not be named?

Given Hamdan’s partial acquittal and sentence, these revelations must have disturbed the jury. They certainly would have shocked any jury in the past. But the trampling of rights at Guantánamo Bay has so permeated the national consciousness (if not its conscience) that such abuse seems almost commonplace—a simple by-product of the war on terror that must be endured.

For example, on day four of the trial, the prosecution called on FBI special agent Dan William. He testified that on August 19, 2002, he interviewed Hamdan at Camp Delta, one of the prisons at Guantánamo Bay. William said that Hamdan was “willing” to talk and the session was “cordial.” He noted that he did not read Hamdan his rights, as it was “policy” at the time not to do so for any Guantánamo detainee.

On cross-examination the next day, Team Hamdan offered a secret document into evidence, and while court observers were not able to see the document, we were told it revealed that Hamdan had been rudely awakened at midnight on August 19-20, 2002, and interrogated by “another agency” of the US government—generally a euphemism for the CIA.

Upon hearing this information, William shrugged. Although he had no idea that anyone else had questioned Hamdan at the same time as he did, he told the defense that he didn’t think secret midnight interrogations undermined his own daytime “rapport building” efforts. One of Hamdan’s lawyers suggested that there might be some kind of “good guy, bad guy thing going on,” with FBI agents “building rapport” during the day and “the other agency” doing things the rough way at night.

Those in the gallery will never know the answer to that. Under an order from the judge, the CIA’s name can’t be uttered aloud in Hamdan’s trial and the secret document is, well, secret.

As FBI agent George Crouch, a prosecution witness, said dryly—after learning that apparent CIA interrogations of Hamdan had taken place at night without the knowledge of FBI agents who were questioning Hamdan during the day—“Nothing surprises me these days.”

Life goes on

One of the hardest things for me to deal with after a long work trip is the transition back into my daily life in Buffalo. I find it difficult to refocus on my children’s homework, dance lessons, and baseball games—and routinely beg forgiveness of my most patient spouse to understand how the stark differences between my work and home life require slow reintegration. I felt that same sense of disorientation going between routine life on the Guantánamo naval base and the work of observing the Hamdan trial.

For many, “Guantánamo Bay” is code for the detention facility, lawlessness, and the abuse of power. But there is an entire community of Americans and foreigners who lived there before 9/11, the prison camps, and the military commissions—and that community will continue on after the detention center is closed. Whatever your politics about the base and US-Cuban relations, many people who live and work at Gitmo told me that they oppose the prison camp and some even staged a small public protest when it first opened.

I was able to interface with the larger Guantánamo population a few times. At the going-away party for the chief of the Guantánamo Bay Fire Company, the firemen—all from Jamaica—gave heartfelt testimonials to a man they clearly held in high esteem. After each one, an emotional Jamaican would pound fist to heart, raise a hand in the peace gesture, and yell “One love!” Eating shrimp curry and swaying to Jimmy Buffett, we could not have been further away in mind or heart from the travesty of the prison camps. Likewise at the late-night Filipino karaoke party (where I and a fellow observer got respectable scores for our heartbreaking rendition of “Don’t You Want Me Baby?”) and at Mongolian barbeque night at the officers’ club, where Morale, Welfare, and Recreation were at it again with an impressive buffet of stir-fried items, two huge grills for the barbecuing, and a romantic patio setting reminiscent of Shanghai Red’s. The mass at nine o’clock the Sunday before I left the island was also reminiscent of themes familiar not only to Catholics, but to all people interested in preserving human dignity. Invoking the golden rule—treat others as you would have them treat you—the celebrant offered a special petition for the detainees.

The two Guantánamos collided on Friday night as that first week of proceedings came to an end. Trial observers went to see The Dark Knight at the military base’s outdoor cinema. The evening was all-American: families with lawn chairs and coolers with beer; public service announcements encouraging the crowd to honor American democracy by mailing in their absentee ballots; and the playing of the national anthem, during which you could hear a pin drop. We were warned in advance not to drop popcorn on the ground because the banana rats—rodents indigenous to Cuba resembling small possums—would come out in force.

Needless to say, it was weird to see The Dark Knight at Guantánamo. The movie is not a simple “good guys vs. bad guys” tale, but a rumination on the nature of good and evil, every person’s capacity for corruption and redemption, and the triumph of basic humanity over self-interest. The Guantánamo Bay detention facility is itself marred by the rendition, torture, and ill-treatment of many of its occupants, and the deeply flawed trials that have commenced there. Ironically, it is precisely these types of indecencies, committed by those with unrestrained power, that The Dark Knight disavows.

Judge Allred was also in attendance at the movie, so I introduced myself to him as an observer for Human Rights Watch. The judge, who clearly took his responsibilities seriously and was mindful of the historical moment at hand, seemed pleased.

“It’s very important that you’re here,” he said to me.

Yes, that’s true, I thought to myself—better to be here than to let the trial go on without anybody from civil society witnessing it.

But I was not glad that either of us was there. A much better place to be would have been on the US mainland, in a federal court, observing a trial that in its essence would be fair, impartial, and just. What unfolded at Guantánamo Bay in the Hamdan trial was very far from that.

Salim Hamdan’s conviction and sentence of five and a half years still leaves several questions unanswered. The judge gave Hamdan time served from the point at which he was formally charged in 2003, which reduced his sentence to five months, but the Bush administration maintains that as an “unlawful enemy combatant,” Hamdan can be held until the end of hostilities with al-Qaeda, which may mean indefinitely.

Click here to view the Commission's findings on the Hamdan hearing (PDF).

Julia Hall is senior counsel in the Terrorism and Counterterrorism Program at Human Rights Watch. She lives in Buffalo with her husband Patrick Mahoney and two children, and telecommutes daily from her home office to Human Rights Watch’s hub in New York.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v7n33: Eight Days in Guantanamo > Eight Days in Guantanamo This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue