The Republic of Oldistan

by Bruce Fisher

How age, depopulation and local politics will shape 2008

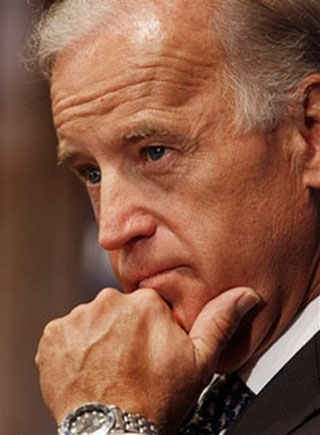

My old boss Joe Biden was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Scranton is an old, poor, rapidly depopulating metro area in eastern Pennsylvania that looks a lot like Buffalo, Toledo, Akron, Youngstown, Pittsburgh, and any number of proud, once rich, traditionally Democratic, sprawled-out cities that dot the landscape between the East Coast and the Mississippi, between the Ohio River and the Great Lakes.

About 18 percent of Scranton’s population is over 65. Between now and 2020, according to an estimate by two Wharton School economists, Scranton will lose another 66,000 people, on top of the 35,000 lost between 1980 and today, out of a 1980 total of around 600,000 people. It’s a poor place, too, except that lots of folks there own their own houses.

Until recently, Scranton has been a Democratic place. The area gave John Kerry a 53 percent to 47 percent victory over George Bush in 2004. It’s had a Democratic congressman since 1984, a man who is very progressive on economic issues—Paul Kanjorski was an early and tough critic of Enron and Wall Street shenanigans. The Republicans put up a small-city mayor against him in 2002, with a campaign that invented a completely theoretical bitterness over illegal immigrants—this in a metro area that is 97 percent white and one percent Hispanic, with no immigrants of any kind anywhere in sight. It didn’t work. Kanjorski crushed him.

But as the late Speaker of the House of Representatives Tip O’Neill said, all politics is local. This year, the 70-something, 24-year incumbent is being targeted by the national Republican operation, and he could lose. The “change” candidate is the Republican.

So Scranton is a bellwether for politics and policy—because like everywhere else in the region I call the Republic of Oldistan, Scranton has every measure of economic distress that should lead to support for a populist Democratic ticket that is going to be fiercely focused on economic issues.

The Republic of Oldistan

The deepest American political cleavages are about race and gender and religion. Arguably the most difficult to address, however, is the gulf between rich and poor. Where one’s racial, gender, and religious identity are enduring, income and wealth fluctuate over an individual’s lifetime. This experiential fluidity, especially because of expectations shaped by the most enduring American hope—that material success can be had through luck, pluck, virtue, smarts, savings, or all of the above—tends to obscure enduring realities. One such reality is that the North is getting poorer. Another is that smaller communities are full of poor old white people. From World War II until 1980, and then again for a brief period in the 1990s, the middle class also saw its earnings and wealth grow.

Overall, though, since the 1980s, the share of income and wealth acquired by the very richest and wealthiest has grown at a far faster rate than at any time in American history. And both federal and state tax policies have generally favored capital gains over earned income, except for the brief period after the enactment of the Tax Reform Act of 1986. Under George W. Bush, even the inheritance tax—which only the wealthiest ever pay—is suspended.

There is a wider public recognition of income and wealth polarization than in recent years. That’s why the “scrappy kid from Scranton” and his running mate will introduce this topic into the political discourse of 2008.

But the other divide is regional. It is between Oldistan, which is the old, cold, shrinking part of America, and the rest of the country, specifically, the Sunbelt, the Coasts, the Rockies, and Chicago.

America has never before had to deal with a huge swath of our country that is in a crisis of shrinkage, aging, increasing poverty, and greater dependency. Back in Dust Bowl days in the 1930s, the solution was to put a few thousand people to work doing WPA and CCC projects, and to let the rest migrate to California.

Most of the states of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, Iowa, Nebraska, the Dakotas, and big parts of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Indiana, are losing population and economic relevance.

American political discourse has a hard time with decline. We are a growth-oriented people—yet between Scranton and Omaha, between Duluth and Syracuse on the north and Carbondale, Akron, Pittsburgh, Wheeling, and Chester on the south, Oldistan is still sprawling, still devouring resources, and still governing itself as if townships and villages were the highest and best form of organization. But it’s not growing. It’s shrinking.

And where there’s decline, and a low birth rate, there’s ugly politics.

The short-term politics becomes all about blame, and not about hope.

The policy debates on what to change, and how to change, lose the hopefulness that comes in the presence of growth and opportunity.

We know all about that in Buffalo. A bipartisan movement to consolidate government—to regionalize, to “cut, coordinate and grow”—has become a rant about lopping off members of individual village boards. Students of policy and economics know that we should be talking about regional planning across the metro area (as they do just across the border in growing, leafy, density-designing, regionalized Southern Ontario) and about reviving our own pretty city and mature suburbs with rehabs, flowers, well-tended seniors and pampered grandkids. Instead, our politics is a rancid scramble to claim the few remaining crumbs. And our governor is oblivious both to the challenge, and to the opportunity.

That’s the way it is all across Oldistan. That’s why a federal policy prescription to fund density and to defund sprawl is the next president’s first order of business.

An Obama archipelago? Or the McCain chain?

Scranton is Joe Biden country. Scranton should be Obama country. The Scranton metro area is 97 percent white. Scranton folks bleed blue—blue coal and blue votes. It’s had the same Democratic congressman since 1984, it voted for John Kerry in 2004, and it was Hillary Clinton country in the 2008 primaries.

This is one place where class-consciousness seems to find unapologetic expression. This is a “regular folks” kind of place—as is the rest of Oldistan.

But it is pretty darn scary that a place that is poor, white, and stable, with a fairly small segment of college-educated folks (only half as many have a BA or a graduate degree in Scranton compared even to the Buffalo-Niagara Falls area) could get so revved up about illegal immigration as they apparently have been.

A politics of hopefulness could actually be more effective than a politics of blame, for, like other inexpensive places, Scranton could see a new wave of investment as bargain-seeking businesses and investors figure out that real estate in Scranton is such a great bargain that it really can’t be overlooked. (That’s the hope of much of the rest of Oldistan, too.)

But in the short term, the genius of the Republican message machine is to create a sense of grievance, and to hammer hard. Republicans are calculating that putting the hammer down in Scranton, Pennsylvania in 2008 could be just the ticket to preventing Pennsylvania from going Democratic.

In Scranton in 2002, the Republican task was to distract, distract, distract the aggrieved older white folks from the trade, tax, and social policies that have left them poorer and lonelier for their Sunbelt-bound children. Republicans worked hard to focus the fears of the uneducated on a threat that simply didn’t exist, and that still doesn’t exist—illegal immigration—in a campaign encompassing Rush Limbaugh’s radio shows and a local mayor’s resolutions for his council. Now there’s a region-wide GOP campaign alleging that the real “change” agent is a candidate who will support the very Bush economic policies that have accelerated the depopulation of the Scranton metro.

That campaign shouldn’t work, but it just might. Demography should be destiny—but Oldistan has time and again voted against its own economic interests. Oldistan won’t get a policy prescription that preserves communities unless Oldistan votes for it. But there is hope. If the choice is between distraction and a fiercely, unapologetically focused populism, the experience, at least in the Scranton district of Oldistan, is that economics wins the debate.

Bruce Fisher is Buffalo State College visiting professor of Economics and Finance, where he directs the Center for Economic and Policy Studies.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v7n36: Fall Guide (9/4/08) > The Republic of Oldistan This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue