To Invest or To Cut?

by Bruce Fisher

If Wall Street gets a bailout, will infrastructure get a boost?

One of the richest and most respected Wall Street investment bankers of our time is actively campaigning for a massive program of public works. Meanwhile, Governor David Paterson’s chief economic development officer recommends tax cuts for economic growth. There has never been a more stark contrast between two radically different prescriptions for economic recovery than the one that is playing out here, in the state that is the home of the finance, insurance, and real estate economy—which just blew up.

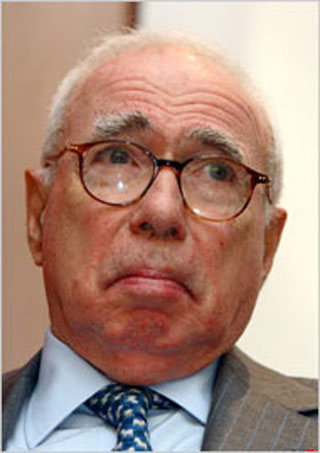

Felix Rohatyn, the former chairman of the investment bank Lazard Freres, advocates creating a National Infrastructure Bank. He led a bipartisan national commission that recommended a federal commitment of $60 billion a year, which would leverage as much as $250 billion of public and private funds, for repairing roads, bridges, public transportation, water and wastewater systems, and other infrastructure, as well as for new policy that would prevent more “bridge to nowhere” investments. Senators Chuck Hagel (R-Nebraska) and Chris Dodd (D-Connecticut) have introduced a bill to create this bank. Barack Obama endorses it; John McCain rails against spending.

Banker Rohatyn is a notable public intellectual and a model of civic engagement. He was the volunteer chairman of the very first “control board,” otherwise known as Big Mac, which was the body created in 1975 to deal with the fiscal crisis of New York City. (New York City had a real fiscal crisis—very similar to the crises in Buffalo, Yonkers, and Troy, each of which lost the ability to borrow money for their normal activities, and needed an entity backed by the State of New York in order to sell bonds for short-term and long-term funds. Erie County’s control board, by contrast, can’t borrow, and doesn’t need to, as Erie County has never lost market access or reached even one-half of its taxing limit.)

Rohatyn has for many years contributed essays to the New York Review of Books under his own byline. His current essay is all about the economics of investing, or failing to invest, in public works. “Regardless of the government’s fiscal position, vital investments in transportation, water supply, education, and clean energy are necessary to maintain our future standard of living,” he writes. “Our political system pours money into war and tax breaks while relying on deficit finance. Those in charge then announce that there are no resources left to secure our economic future. The new bank we propose offers one alternative to such a dangerous set of policies.”

Meanwhile, the Buffalo banker who heads Governor Paterson’s Empire State Development Corporation, M&T Bank’s Robert Wilmers, is known as a fiscal conservative. Year after year, in his annual report to his shareholders, Wilmers has consistently hammered state and local government in New York for taxing more than other states. Wilmers’s speechwriter, Howard Husock, a longtime leader at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, is a regular contributor to the strongly right-of-center City Journal of the Manhattan Institute—the journal that published Edward Glaeser’s curious article about Buffalo last year, in which Glaeser essentially said that investing public money in infrastructure in Buffalo was a complete waste. (Husock wrote in 1998 about how localized government is better than metro government, and expressed his opposition to consolidation quite forcefully.)

This is one heckuva curious time for these two approaches to be doing war inside the home of AIG, Bear Stearns, and all those other financial firms that will be receiving hundreds of billions of dollars—federal taxpayer dollars—because of a Washington consensus that without a bailout, the rest of the American economy won’t be able to borrow money for normal activities.

The hit to New York State

New York-based financial companies have announced 103,000 layoffs this year, everyone from traders to aides, according to outplacement firm Challenger Gray & Christmas. The comptroller of New York City estimated in July that about 83,000 fewer people would be working there by year’s end.

That means less revenue for governments. Mayor Michael Bloomberg hopes that the economy of his city is diverse enough to weather those losses. Bloomberg gave a tax cut a couple of years ago, while upstate county executives were all raising taxes to deal with the Medicaid burden. The governments run by Bloomberg and by Governor Pataki got lots of tax revenue from all the astounding salaries and commissions and high-end consumer spending of the “bubble” years. (For the five years between 2004 and now, just the top CEOs of the top banks took home a collective paycheck of over $3 billion, according to Barron’s.)

But now job losses are coupled with sagging taxable real-estate values, which means that revenues to provide services will shrink. Bloomberg has announced a $1.5 billion cut in his budget, and a seven percent increase in property taxes.

Governor Paterson has it much, much worse. The deficit he and Spitzer inherited from George Pataki was already over $4.6 billion. Like Bloomberg, Paterson has signaled already that he will cut spending. Sources in Albany tell me to expect sharp reductions in aid to counties, cities, and school districts—a phenomenon called “downloading” that will leave local governments with the choice to raise taxes or to cut spending on basic services.

It would seem, then, that the Wilmers view rather than the Rohatyn view is guiding policy in New York.

But Albany is also discussing a “millionaire’s tax,” to be enacted when the legislature convenes after the November elections.

Earlier this year, Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia University sent a letter to Paterson urging the governor not to cut spending, but instead to raise taxes—specifically, to raise them on high-income individuals.

“The reasoning is straightforward: in a recession, you want to raise (or not decrease) the level of total spending—by households, businesses and government—in the economy,” wrote Stiglitz. “That keeps people employed and buying things, and makes it more likely that businesses will want to invest to serve that consumer demand.”

Stiglitz pointed out that “every dollar of state and local government spending enters the local economy right away,” in contrast to the luxury-goods purchases of high-income individuals.

“The impact is especially large when the money goes for salaries of teachers, policemen and firemen, doctors and nurses and others that provide vital services to our communities,” he wrote.

“America today faces two major problems—inadequate investments, especially in infrastructure, and growing inequality,” Stiglitz summarized.

Rohatyn, Stiglitz, and Obama versus Wilmers and McCain

We in upstate have to care about how New York City and Governor Paterson handle this fundamental difference in economic thinking.

That’s because Upstate New York has fewer people than the New York City metro area. We actually have fewer people than New York City itself has, notwithstanding the slight drop in population in New York City over the past several years. And upstate’s people are tax-revenue eaters, not tax-revenue producers. As of 2004, according to a study by Mayor Bloomberg’s budget office and Rochester-based think tank CGR, the “balance of payments” inside New York State was $11 billion in favor of upstate’s 53 counties, which means that the five boroughs of Manhattan and the four suburban New York City counties gave New York State $11 billion more than they got back in state services, salaries, and stuff.

And what’s doubly troubling about our upstate economy is that some of our new-found “strength”—namely, our decreased reliance upon manufacturing for high-wage employment, and an increased number of jobs in the finance, insurance, and real estate, or FIRE, sector—now exposes the region to the same potential job losses as have afflicted other areas of the country that have big FIRE workforces.

In the next two months, as we see whether the Washington bailout of Wall Street actually stops the credit crisis from further damaging the American economy (and the world economy, too), another drama will play out, much closer to home.

The drama will consist of daily headlines as county executives and mayors compose their budgets for 2009 and beyond.

The big drama, after the election, will come in January, when we get our first look at Governor Paterson’s first budget.

Will it be a Rohatyn-Stiglitz budget, full of spending to stimulate economic activity with investments that will make the state technologically and educationally competitive? Or will it be a Wilmers budget, with slashed services, reduced spending, and tax cuts, an exemplar of fiscal restraint rather than of fiscal stimulus?

That’s the old dualism of 20th-century American politics. How strange, though, that we are now in a new paradigm, in which a Republican president in Washington puts forth a program of almost $1 trillion of public spending to intervene in what had been private transactions, after having spent down a surplus and creating the largest deficits since the 1980s.

With such complexity, with such fundamental change in the meaning of the word “conservative,” it’s no wonder that so many sophisticated people are now beginning to say that they’d like to see some concrete and some re-bar and some fiber-optic cable and maybe even some wind turbines—some actual tangible objects—after the government spends a few hundred billion taxpayer dollars.

Call me old-fashioned, but I kinda like to be able to go and walk on my money, or ride on it, or hear it in the form of a SUNY lecture on economics or physics or engineering or poetry, whatever, rather than just see it chase around a bunch of financial instruments based on chopped-up mortgages.

Bruce Fisher is Buffalo State College visiting professor of Economics and Finance, where he directs the Center for Economic and Policy Studies.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v7n40: Crude (10/2/08) > To Invest or To Cut? This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue