Next story: The Past Present

Trans-Evolution: Examining Bio Art at CEPA Gallery

by Lucy Yau

Art Imitates Life

On view at CEPA are three exhibits celebrating and examining the consequences of bio art.

Bio art is the fusing of contemporary biochemical and medical research with visual art. Though it may seem like a new conceptual fad, bio art has a long tradition. Over the centuries the division between the arts and sciences has grown wider, where once they were tied closely together, as in the artwork and scientific discoveries of Renaissance luminary Leonardo da Vinci.

Bio art asks public and private institutions to question the ethics and ramifications of the latest technologies in present and future society.

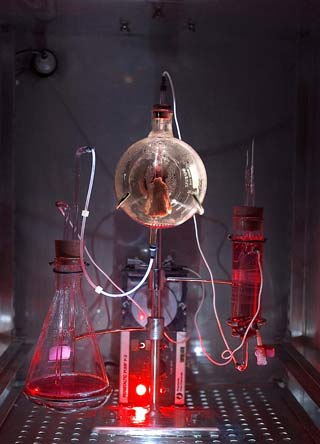

Latent Figure Protocol by Paul Vanouse delves into the issue of DNA fingerprinting. Vanouse highlights a plasmid, a non-living organism that lives symbiotically within a bacterial host for gene therapy called pET-11a. Plasmids are smaller than even molds or viruses. Video footage taken during the exhibit’s opening shows the plasmid DNA manipulated with chemicals and electricity.

Vanouse contends that DNA fingerprinting is more a cultural than a scientific construct. We are led to believe that DNA offers a static image of a person, but in fact DNA is very dynamic. “DNA fingerprinting is an interchangeable process,” Vanouse says. “The image tells us more about the laboratory than the individual. Labs use different enzymes, chemicals, probes, gels, voltage. DNA images change from lab to lab with different parameters. They are a more accurate portrait of the labs than the individual.”

Vanouse cites Dwight Adams, chief of the FBI Laboratory, who says of DNA fingerprinting that the term “invokes in the mind of the jury that we are identifying one individual to the exclusion of all others.” He also cites geneticist Alec Jeffreys, who said, “If we had called this ‘idiosyncratic Southern blot profiling,’ nobody would have taken a blind bit of notice. Call it ‘DNA fingerprinting,’ and the penny dropped.”

In Victimless Leather and NoArk, Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr construct multi-media presentations out of living tissue. Both artists are part of the Tissue Culture and Art Project (tca.uwa.edu.au).

Catts and Zurr are fascinated by the breakdown in traditional Linnaean taxonomy. Such boundaries between animal and vegetable are no longer valid in an era when scientists can combine frog and carrot genes. Under what categories will such new creations be classified?

Such taxonomies began in the 17th century, when the wealthy collected odd specimens for curiosity cabinets. Among the oddities were genetic mistakes—the errant two-headed calf or a sheep with an extra limb. The idea that “God got it wrong” with inferior copies created a religious controversy that led to the rigorous examination of nature, culminating in Darwinian evolution.

Catts and Zurr view living tissue as a material to be manipulated and engineered. They sculpt and fuse tissue, re-evaluating definitions of nature and what constitutes life by combining blobs of hybridized human, animal, and vegetable DNA.

Victimless Leather consists of a synthetic biodegradable polymer mold upon which living rat tissue has been placed to create leather.

The concept for the piece, which was shown at MoMA, arose from a PETA-sponsored idea for producing meat in a humane fashion: in-vitro meat.

Catts and Zurr also examine the least conditions under which tissue can survive—a few test tubes, bottles, and containers containing fragments of life, unclassifiable sub-organisms.

Corpor Esurit, or we all deserve a break today by conceptual sculptor Elizabeth Demaray was inspired by the Morgan Spurlock film Supersize Me. (Corpor esurit translates from Latin to “the body hungers.”) Working in conjunction with Dr. Christine Johnson of the American Museum of Natural History and Rutgers University, Demaray looks at how harvester ants behave on a three-month McDonald’s diet.

One reason Demaray chose McDonald’s, besides name recognition, is that the chain’s food doesn’t get moldy that fast and therefore doesn’t need to be replaced often.

“I wanted to create a line drawing of the ants eating, burrowing, tunneling, making houses,” Demaray says. Her exhibit contains what may possibly be the world’s largest ant farm. Housed in five galleries, the ant farm consists of their main habitat connected to foraging areas. A detailed menu of McDonald’s meals and their ingredients is displayed in a separate gallery. Among the expected ingredients are food coloring and preservatives. There are surprising ingredients, too, such as anti-foaming agents.

Johnson says of the ants, “They have their own system of logic. It isn’t anything like people’s logic and yet it takes place right under our feet. Their system of relationships allows them the ability to adapt to many adverse, unusual environments much like humans.”

Viewers are invited to document the progress of the ants by creating diagrams on worksheets. At the end of the three months, Johnson and Demaray will evaluate the ants’ foraging behavior and egg production.

Demaray attempts to communicate things that language cannot, she examines things that, she says, “can be beautiful and ugly at the same time.”

Trans-Evolution: Examining Bio Art will be on view at CEPA (Market Arcade, 617 Main Street, 856-2717 / cepagallery.com) until December 29.

—lucy yau

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v7n41: Trans-Evolution (10/9/08) > Trans-Evolution: Examining Bio Art at CEPA Gallery This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue