Next story: West Side activist stows chickens in secret location, pleads with city to make them legal

Interview with Greg Ames, author of novel Buffalo Lockjaw

by Geoff Kelly

The first novel by Buffalo-bred writer Greg Ames namechecks familiar bars, restaurants, street corners, and assorted Buffalo institutions and legends. But don't fret: You're not in it.

Greg Ames left Buffalo for Brooklyn 10 years ago, having spent his 20s here in much the same way many Buffalo artists spend their 20s: on barstools and in coffee shops, at parties and in galleries, among like-minded people, all of them hard at work on finding a medium and a voice. Back then, this paper was among the first to publish his writing—usually very short pieces of fiction, 500 words or less, that earned a gamut of adjectives: surreal, snappy, funny, hardboiled, touching.

Eventually Ames pulled stakes and left for New York, where he found a new community and new outlets for his writing. His stories have been published in The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2007, Open City, McSweeney’s, The Sun, Fiction International, Pindeldyboz, failbetter.com, and Other Voices. He’s a frequent reader at the KGB Bar in Manhattan, and received honorable mention in the 2003 Pushcart Prize Awards and in the 2004 The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2004. He has taught fiction at Brooklyn College and at Binghamton University.

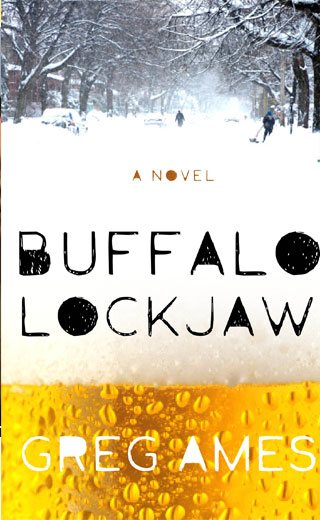

And now he’s published his first novel, Buffalo Lockjaw, which is set in Buffalo over a long Thanksgiving weekend. The protagonist, James Fitzroy, has returned from Brooklyn, where he writes copy for greeting cards, to see his family. He has brought with him a copy of a book called Assisted Suicide for Dummies, having determined that it’s past time for someone in the family—for him, in fact—to do something about his mother, whose progressive dementia has confined her to the misery of an assisted living facility and will eventually kill her.

James, a bit like his hometown, is self-absorbed, mildly alcoholic, seemingly a victim of chronic inaction; he is also moved by a nagging impulse to overcome those obstacles and transform himself, to find a more gratifying way to live. James searches the city for old friends and his lost self, recalling a time before his mother’s vibrancy was stolen by her disease, and wonders if he’s capable of doing what he believes he ought to do.

Abetted by that narrative, the author propels James through old haunts in Allentown and along the Elmwood strip, and populates those streets with familiar Buffalonian types, turning the city itself into a character. For good measure, Ames interrupts the narrative on occasion with snippets from James’s long-abandoned oral history project: As a young, would-be writer, James records and transcribes conversations with city’s shopowners, bartenders, and sundry oddballs. These oral histories for a moment draw the book out of the imagined world of James’s reminiscences—even out of the realm of Ames’s fiction—and make the city a real place.

It’s a thoroughly engaging read, an auspicious first novel. And it’s set in Buffalo. What other reasons does one need to pick up a copy? Ames will be in town next week, reading at Talking Leaves Books (3158 Main Street) on Wednesday, April 8, at 7pm. He reads again at Borders (2015 Walden Avenue) on Thursday, April 9, at 7pm.

I spoke with Ames earlier this week, and here’s some of what he had to say about the book:

AV: Tell me about the oral history project. Was that actually a project of yours?

Ames: No. I’ve been writing this thing for so long, and I’ve had so many different versions of it. It existed in present tense, past tense, first person, third person. I just couldn’t get it. For a long time I thought the book was the mother’s story, and I was trying to write that. Then I cut about 100 pages about the mom; when I realized it was James’s story, the book started to come together. And it really took a nice shape, but it existed without the oral history sections. I think that my agent had already accepted the book without the oral history sections.

I thought, “Well, two things it’s not doing here: It’s not bringing Buffalo forward, and it’s not giving the reader enough of a break from the story.” So I thought, “How do I make Buffalo more of a character in the story without wedging in static passages?”

AV: Like descriptions of the architecture or the Buffalo River.

Ames: Yeah, like “It flows majestically…” I don’t know how I came up with James’s oral history. It was never anything that I did, but it was something I had contemplated: I wanted to make a book of people just talking about Buffalo, but of course I never did, so I made it up. Then I just filtered in all kinds of references to the oral history project.

AV: Those sections add a dimension to a character who, at times, might seem to the reader to be insufferable. You see that he’s quietly working on something kind of cool, even if he’s not going to see it through to its finish, and you think more of him.

Ames: I did think, when I was writing it, “Should I try to make this guy more likable?” And I thought, “No, I’m not going to.” That’s one of the things I’ve always rejected about books and about writing. The critique I sometimes hear is “I just didn’t like any of the characters,” and I just never thought that was necessary.

AV: That is a temptation for a writer of fiction, isn’t it? To charm and flirt with the reader through your narrator or some other character in your book, to draw the reader in and say, “Like me.”

Ames: I think that is a temptation, and it’s especially a temptation when you’re a younger writer. I feel like maybe I would do that a little bit more 10 years ago. Now I think that if there’s going to be any charm, it should be in the sentences. The book I’m working on now, I think the guy is more charming, but it’s not like he’s trying to be; he’s just a different personality.

I think that Buffalo Lockjaw is sort of about the passage from selfishness to selflessness. James is certainly not selfless, but I thought of it as this Buddhist idea: I wanted to write an entire book about a guy who takes one step. After 275 pages, he takes a single step toward being a better guy.

AV: Can you tell us about the story you’re working on now?

Ames: I do adhere to the Hemingway dictum that if you mouth it up too much, you’ll trick your brain into thinking you’ve done it. So I don’t want to talk about where it hasn’t gone yet, but I’ll tell you where it has gone. It’s about a guy who has been living in a college dorm for 12 years, and he’s been forced out into this sort of adventure. It’s basically just a really big fat comic novel. I’ve never had more fun writing a book, and it’s just been pouring out of me. This Buffalo Lockjaw thing was like clog in the drain.

AV: Why, because it was your first novel? Is the novel your form now?

Ames: I would like to think so. I’m so smitten with it. I love the short story, and I’ll continue to write them, and I still have 10 or 15 on the hard drive that I’d like to see published someday, but I’m really interested in the novel. It’s an inexhaustible form. It’s taken over my imagination in the same way the short story did for much of my 20s and early 30s.

AV: It must be a tough transition. My first exposure to your writing were the short, short stories published in Artvoice more than 10 years ago.

Ames: Artvoice taught me how to write. I would write these pieces for—I believe it was called “The Word” at that time. I think it was in 1997 or 1998; I would read Artvoice each week and I would see that column and I would think, “I can master that, I can get a story into that column.” I was also a huge Chekhov fan, and still am, and the Norton Critical Edition of Anton Chekhov’s stories contains about 20 of these 500-word short stories, and I just think they’re perfect. They’re little gems. I wanted to attempt something like that. Of course, I never came close to what he was doing, but I liked the idea of a completed story in that small space.

I started sending stories to Ed Taylor at Just Buffalo, and he was a great champion of my work for a long time and really helped me a lot. In fact, just the other day I was reminiscing about the late ’90s and my life in Buffalo, and I found this amazing cover letter that he wrote for me on the Just Buffalo letterhead, and it really predicts my writing. He knew my writing and where I was going with it, what my style was, more than I did.

I think the short short story, obviously it’s closer to a poem than it is to a novel. It’s very difficult to get something across, and I failed more than I succeeded.

AV: Did the struggle to finish this book have to do with working long, pacing things out over many pages?

Ames: Yeah. I think Scott Fitzgerald said to Thomas Wolfe, “You’re a putter-inner, I’m a taker-outer.” I’m a taker-outer. I had to become more of a putter-inner. I had trained myself to run sprints and then I’m running a marathon, and I didn’t know how to do it.

For a long time the story didn’t even have an engine. The book didn’t have any kind of narrative drive until I woke up one morning and I realized, “She has to die.” That was number one, and the next thing was “He’s got to feel obligated to do it.” Once I knew that, then I could drape all the other information onto that, and it would carry the reader through the book. Until then, I didn’t know how to do that.

AV: You kickstart that engine in a very Chekhovian way: James arrives in Buffalo carrying copy of a book called Assisted Suicide for Dummies. We know somebody’s going to die.

Ames: I don’t know if you’ve read Jesus’ Son by Denis Johnson, but there’s a great line where this guy shows up at the farmhouse, and Dundun has shot someone. The guy says, “What happened?” and this other character, Jack, doesn’t want to get involved, so he says “Somebody shot somebody.”

AV: Here’s an obligatory question for the first-time novelist: How autobiographical is this? Will folks around here recognize themselves in the novel?

Ames: No. It’s so funny, a good friend of mine from childhood got in touch with me just yesterday, and he said, “I remember sitting in your bedroom when we were eight years old and you were always writing down stories.” He’s known me for most of my life. He said, “I hope you changed the names to protect the guilty.” And I said, “I do want to get all those stories from you guys, but this book is all made up.”

Nobody is going to recognize themselves in this. There are some autobiographical elements in the narrator and his immediate family, but it is a work of the imagination. I don’t suspect anyone is going to say, “That’s my backyard!”

AV: It’s interesting to me that writers ascribe autobiography to characters and events, but not to place. No one asks for a release form from a place.

Ames: That is really strange. I’ve been in New York for 10 years now, and I set many of my stories in Buffalo. It’s still very much my home and my hometown, but I do it because I’d rather do that than make anything up or do any kind of research. Place names have a certain magic for me, but they’re also kind of easy. I may be in the minority of writers: I don’t spend that much time thinking about place. I’m fond of those Carver stories where everything is indoors. It could be anywhere. He doesn’t name a street, I think, in his entire work.

I think that the truth that hopefully people will find in this book has nothing to do with “This actually happened.”

AV: But you’re creating stories that resonate differently for people who live here. You wrote a piece called “Five Dollar Donut,” for example, a kind of pastiche of a noir potboiler, where a private detective wakes up in his office on Grant Street. Knowing what I know of Grant Street, and knowing that you know what you know, the setting threatened to derail my reading of the story. I kept thinking, “Huh, Grant Street,” even paragraphs later.

Ames: Yeah, okay. But imagine the difference if it was “I woke up on Linwood.” What I liked about “Grant Street” there was the words themselves. Anyone from Buffalo knows, “Okay, this must be a seedy, down-on-his-luck private eye.” But “Grant” has that solidity and that strength, and you think of U. S. Grant, and there’s this juxtaposition: This guy is a weak-willed, incompetent, bumbling drunk, but he’s got his office on Grant Street.

AV: In Buffalo Lockjaw, James seems homesick, but reluctantly so.

Ames: I think he’s very homesick for his family. He’s homesick for the city, but he’s realizing that the only way for him to mature is through developing his own life apart from his family. What I wanted to be implicit there is that his reminiscence is also for a time when his mother was a vibrant person, when he had far fewer concerns and didn’t even know it. He’s certainly homesick for a time when things were easier—in his mind, at least, because he’s so invested in fantasy, it might not have been easier and probably wasn’t.

I think I actually cut a paragraph where he realizes, “Hey dummy, all these people have moved.” All these people he’s looking for have husbands and wives and kids and careers. That’s where they are. They may be in Buffalo, they may be in Charlotte, but if you’re driving up and down Allen Street looking for those people, they’ve moved on. It makes it clear to him that he hasn’t moved on, and how is he going to do that? He’s got to become an adult.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v8n14 (Week of Thursday, April 2, 2009) > Interview with Greg Ames, author of novel Buffalo Lockjaw This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue