Next story: Modest Mouse - No One's First and You're Next

Duayne Hatchett at the Burchfield-Penney

by Lucy Yau

Time Machines

Duayne Hatchett will proudly tell you that his grandmother raised him in Oklahoma during the Depression. “My grandmother was born in Indian Territory,” says the artist, who is the subject of a retrospective exhibit at the Burchfield-Penney Art Center. “We’re Okies. Because my mother passed away when I was five weeks old, my grandmother raised me.”

Indeed, he credits his grandmother with nurturing his artistic talent. His piece Escape (1949), a black-and-white lithograph, is a stark representation of the conditions under which he grew up: His grandmother holds him in a protective embrace against a howling wind.

Growing up in the Dust Bowl still informs his work. Study in Time (1995) is composed of 64 logs locked in a steel frame, their rings exposed. “These trees were planted to stop erosion at a time I was tied to—during the Dust Bowl period,” he says. Armadillo Race (1998), composed of railroad spikes, is a narrative sculpture about a race he had when he was nine with an armadillo. Hatchett says, “I was barefoot all summer and we had a street that was clay and when it rained cars would get stuck, so they put down sand. When you do that in the summertime in Oklahoma, goatheads get started. Goatheads—this particular plant, the blossoms form and two spikes stick out, so this plant goes around over the surface of the sand. My plan was to run down the street barefoot without stopping and get stuck. I took two steps and on the sidewalk was an armadillo, and it would stop when I stopped. I would take a few more steps and it would stop, until at the end of the street it ran into a culvert.”

Hatchett was the youngest artist sponsored by the Works Project Administration, but his art career took a detour when he was drafted during World War II. He trained as a fighter pilot. While stationed in Paris, he took every opportunity to tour the Louvre, often the only guest in the empty galleries. (The statue of Winged Victory especially influenced Hatchett: Abstract distillations of the piece can be seen in Winged O 1 (1960) and Winged Bird (1960).) After the war, thanks to the GI Bill, Hatchett studied at Oklahoma University with the printmaker Emilio Amero, a colleague of Diego Rivera. There, Hatchett met Mary Ellen Jeffries, who would become his wife. Their marriage lasted more than 50 years. One of the tenderest aspects of the Burchfield exhibit is a display of the palm-sized sculptural collages he made for her every Valentine’s Day, constructed of found objects, bits of painted steel, wood, pins, bolts and chain. Although Mary passed away in 2006, he still continues to make them in memory of her.

Found objects are a prominent theme in Hatchett’s work. His sculptures from the early 1950s are rough in texture, composed of scavenged scrap metal and railroad spikes. In the next decade, he gravitated toward totemic figures, squat stacked forms with post-like bodies. He continued to paint during this period, too, flirting with abstract expressionist forms in pieces like Seascape (1953), Painted Strip and Burlap Collage (1955), and Barrier Age (1958). In the 1960s and 1970s, Hatchett’s sculptures took on a sleek, minimalist edge. Larger compositions such as Arc (1967) and North by Northwest (1968-69) incorporate dynamic arches, circular forms, and interior triangles interlocked in fluid forms.

In 1968 Hatchett became head of the Sculpture Department at the University of Buffalo where he taught for nearly 30 years.

For the collage Still Clyfford (1966), Hatchett carefully shredded a poster for a Clyfford Still show at the Albright-Knox. Hatchett made the piece after he and his son encountered Still at his show and Still was rude to them. “We were surprised he was such a nasty character. We found out later that’s his attitude, it’s his personality, he’s like that with everybody. As soon as we left him I went downstairs to get his poster and got a shredder and shredded it.”

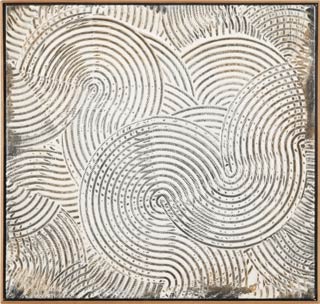

Over the decades Hatchett has created his own tools with which to make his artwork: Specialized crimpers, scrapers, and trowels for his sculptures and prints are in a separate display case, with text explaining how he fabricated these devices. In the 1980s, Hatchett began working with harmonographs to mechanize the drawing process. He constructed table-sized platforms and hung brass plumb bobs to which he attached colored ink pens. He would let them go and watch the patterns that emerged.

Recently he’s engaged himself again in the printmaking process, using a press with lead plates and found objects such as bottle caps, clips, roofing paper, and feathers. Some of his boomerang-inspired prints date back to his fascination with aviation. “I met Amelia Earhart when I was seven,” he says. “I had an uncle who took his son and me to the back of Shawnee Baptist University, where there were weeds knee high. There was an antique gas pump there and for some reason this uncle was a genius and figured out she was going to land there. So we waited in those weeds and waited, and pretty soon she met us two little jerks, and my uncle helped her gas up and she took off.”

At 84 years old, Hatchett still works on several pieces at once, inventing and developing new processes to explore innovative forms. Duayne Hatchett: Form, Pattern and Invention: A Retrospective continues at the Burchfield through the end of August.

—lucy yau

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v8n34 (week of Thursday, August 20th, 2009) > Duayne Hatchett at the Burchfield-Penney This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue