Next story: Not Quite the Last Picture Show

Pictures From a Drawer

by Geoff Kelly

After 30 years, photos from Cummins prison in Arkansas result in two new books and a photo exhibition at the Albright-Knox

Bruce Jackson was first drawn to work in prisons during the folk revival of the 1960s. Inspired by folk music collectors like the Lomaxes, he set out to capture work songs sung by African-American convicts, going first to Midwestern prisons when he was a graduate student in Indiana, and later to Texas state prisons while a fellow at Harvard. Over many years and in many prisons, he found and recorded the songs he was looking for, conversations with inmates, guards, and wardens, and thousands upon thousands of photographs. He made the first and only film of black convicts singing those work songs—Afro-American Work Songs in a Texas Prison—and many of his photos illustrated or became the principal material for a string of books Jackson produced in the 1960s and 1970s, including Wake Up, Dead Man: Afro-American Work Songs in Texas Prisons, Thief’s Primer, and Killing Time: Photographs from Arkansas State Prison.

Recently Jackson has found the means to revisit some of his work in Arkansas’s Cummins prison. Last year, at Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies, he exhibited a series of photos shot at Cummins with a Widelux camera, which swings on a turret, making an image nearly twice as wide as an ordinary 35-millimeter print but without the distortion a wide-angle lens creates. The Widelux offered Jackson a new range of compositional possibilities but posed tremendous technical difficulties in processing and printing—hurdles resolved by today’s digital editing tools and high-quality digital printers. The Duke exhibit became a book published last year, Cummins Wide: Photos From Inside the Arkansas Prison. Albright-Knox Art Gallery director Louis Grachos, who helped Jackson to conceive the layout of the Duke show, invited Jackson to show the same photos at the Albright-Knox. That show opens this Friday, January 23.

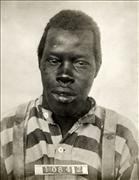

In March, Temple University Press is bringing out Pictures From a Drawer: Prison and the Art of Portraiture. The book comprises entry and exit photos of prisoners at Cummins in the first half of the 20th century—mugshots that Jackson found, as the title states plainly, in a drawer. These remarkable photos, preserved by Jackson and resurrected through judicious use of Photoshop, are bracketed by an essay on photography and its uses, neatly balanced by Jackson’s reflections on the two decades he spent working in prisons, and a convict’s first-person account of what Cummins was like in the decades before Jackson first came there in 1971.

Like the Widelux work, the worn, faded mugshots languished for 30 years, unfinished projects that awaited the tools Jackson need to deal with them. Jackson spoke to AV recently about Pictures From a Drawer, Cummins Wide, and many years working in prisons.

Jackson: The pictures in Pictures From a Drawer are old pictures that were covered over with yellow, and some were faded, and some were beat up. I found them in 1975. I couldn’t do anything with them.

I always wanted to make them big. Because, as I say in the introduction, the whole purpose of photographs like this is to make people small, to make them part of a bureaucratic dossier. It’s all about the institution and system and the apparatus of control. They’re nameless…in a lot of ways, their being nameless was even more appropriate then being named in a file, which is buried in a box, which is buried in the basement of a building.

The darkroom technology I had at the time, I couldn’t do it. Doing color at home was very difficult in the ’70s, and shopping it out was extremely expensive. I looked for a few grants; nobody cared. So I couldn’t do it. But then come the more recent versions of Photoshop. Photoshop CS4 that’s out now, you can do anything with any image just about.

So what I always wanted to do with these—I had this idea from the beginning—was to get rid of some of this patina of yellow. But not get rid of all of it, because not only are these photos of people, they are also objects in time. They are objects with their own trajectory through time. Some of them you can see it: There are creases, staples, paper clips, occasionally writing. You can see that these things have been in the world, so I wanted to preserve that.

With Photoshop, I could have cleaned them up. If I were doing a family photograph, if somebody said, “Here’s my grandfather, can you fix this up for me?” I’d say, “Sure,” and I’d give you a real clean picture back. But that’s not what I wanted to do here. I didn’t want to look at them in a way that pretended they were present photographs.

AV: Of all the things that happened to these photos—coffee stains, rips—you now have had the greatest impact on them. You are now the artist in a way the original photographer never meant to be. What did you bring to them?

Jackson: Stieglitz used to say that when you take something and you put it on a wall, you change what it is. You might say you’re not doing art, that you’re doing documentary or something like that; but you put it on a wall in a gallery, you’re making a claim of art. You’re saying there’s a maker’s hand that was involved here. And here there’s a maker’s eye in how it’s done. That is, I applied to this what was my sense of what that photo ought to look like in the present, in that complex sense I told you about before—that is, the sense of something that is of a real person, a person that, as James Agee says, “has weight in the world,” in that wonderful passage early on in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, where he talks about the difficulty of doing the kind of documentary writing that he wants to do. He says he’s always trying to represent somebody who’s real, and there are no words that can do that. You can talk about it, but these are words, and he has weight. He has weight on the earth, his foot makes the dust move, words don’t do that.

I have this sense of these people, and this sense is based on me having spent really a lot of time working in penitentiaries. I’ve been in maybe 25 of them, and some of them I spent a lot of time in, doing various kinds of research, talking to people.

The people who are in penitentiaries are no different than the people outside, except that they’ve done a certain thing that got them classified as the kind of person that goes to the penitentiary. But they’re in a penitentiary, and being in a penitentiary does something to people. It puts you in a position. All the things that Foucault writes about—about power and what it does and the way it’s used—are there. Prison is a place where power rules. Prison is about power; if it were not, people would walk out the gate. You see it in the way people walk and in people’s faces and the way they present themselves. They’re prisoners. The woman who’s on the cover, I think she’s beautiful, she’s got gorgeous eyes. If I saw her on the street I’d think, There’s a beautiful woman. But that picture is not on the street. That picture is in the penitentiary.

I think my sensibility came from that long experience working in the penitentiary, and long experience doing photography. There’s a tradition of documentary photography that I very much see myself in. There are people who are my heroes of documentary photography, whose sense of the human face and relation to the flat piece of paper I think about—like Walker Evans and people like that.

AV: The photos in Pictures From a Drawer have some of the qualities of Evans’s work, but without his intention.

Jackson: One of the things I love about these pictures is…I don’t want to use the word naive, because that suggests that the person who operated that camera didn’t know what he was doing. He knew what he was doing. He’d done it thousands of times. But one of the things he did was manage to capture a look of people in a certain time, a certain place, a certain condition, that I find now, going on a century later for some of them, absolutely compelling.

AV: Can you talk about your academic work in prisons? How did it start?

Jackson: I started doing research in prisons as a consequence of the folk revival in the 1960s. I got interested in folk music, I had heard about the Lomaxes, and I wanted to find original material, so I started going to prisons. I went first to Indiana state prison and the Missouri state prison—that was while I was a graduate student in Indiana—and I recorded music, and I also recorded conversations. Then I got to Harvard. I had a four-year fellowship at Harvard that allowed me to do anything I wanted and they paid all my expenses. It was incredible. It was astonishing. It was like being rich, because you don’t have to worry, “Can I afford to do this,” and that’s what being rich is.

So I started going to Texas, because I had read stuff about Texas in the ’30s as being one of the worst prison systems in the United States, and I wanted to see what it was like.

The director of the Texas prison system was a guy named George Beto. I wrote him on my Harvard letterhead and said, “Can I come down? I want to record some music.” And he wrote back and said, “Sure.” At that time Texas had 13 prisons and I had the prison units I wanted to go to. He said, “Why do you want to go there?” I said, “Because those are the ones I read about in this—” And he said, “You read that 1936 report.” And I said, “Yes, I did,” and he said, “That’s not where you want to go. Nineteen thirty-six, that’s where you wanted to go. Now where you want to go is, you want to go to Ramsey and you want to go to Ellis.” I was naturally suspicious, and he said, “Look, you go try these places. If you don’t find what you want there, you can go to the others. I’m just trying to save you time.”

So I did what he said, and he was absolutely right, it was what I wanted. I wanted to talk to people who’d been in penitentiary a long time, and where he sent me was the perfect place.

AV: Why black convict songs?

I was interested in the black convict work songs because they go back to a slavery time musical traditon which in turn goes back to an African musical tradition. It’s a pure, unbroken line of musical performance and style, and the way music and physical labor integrated with one another.

At that time I used to perform in joints. The first time I heard black convicts singing these work songs in the fields of Texas, I never performed again. I decided I was totally full of shit: Here I was a white Jewish kid from Brooklyn, New York, singing black folk songs, and these guys are out there with axes cutting down live oak trees in the Brazos River bottoms. I never picked up a guitar again.

I did a book of those work songs called Wake Up Dead Man: Afro-American Work Songs in Texas Prisons. It was published by Harvard. I did several LPs, some of which have been republished as CDs. One of them got a Grammy nomination.

One time I was down there and I got a call from Pete Seeger, who I knew from the Newport Folk Festival. Pete said, “Those work songs you’re studying, there are no films of them. We should make one, because as soon as integration comes in they’re going to disappear.” And I said, “I’d love to, but I don’t know anything about filmmaking, and also no one is going to give us money to do it, because I’m nobody and you’re a Communist.” He said, “It’s too important, I’ll pay for it.” So Pete, his wife Toshi, and his son Dan came down to meet me at Ellis prison just north of Huntsville, Texas, in March 1966, and we spent a week or so filming these things. And it turns out it is the only film of these black convict work songs anybody ever made. It’s called Afro-American Work Songs From a Texas Prison and it’s available online.

AV: How did you and Diane Christian come to do your documentary work on death row?

Jackson: In 1978 I was giving a lecture at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas, and I was invited to a prison barbecue. Two things happened at that barbecue: One was that I found out about a practical joke that had been played on me in 1964, which they had been laughing at ever since. The other, I was asked if I would be a witness for the state in a civil rights case that had been brought against it for maltreatment by prisoners.

Now politically, I’m very left, and I’d written anti-prison articles for The Nation and The New Republic, which back in those days was still pretty left and not like what it is now. I was an activist. So I said, “Come on.” And they said, “All we want you to do, is if you would talk about the differences between what [the Texas prison system] is like now and what it was like when you were here. We don’t want you to lie or anything.”

Well, I figured they had given me carte blanche to go around that place, they had let me sit in on anything, they had let me look at records, they had let me walk the halls day or night. I could go there at two in the morning, and sometimes did. I had total access. I felt like I couldn’t say no. On a human basis, I’d be a real shit if I refused. So I said okay. That caused me some grief, as you might imagine, not much but a little.

I said, “I’ll do it, but if I’m going to do it, I’ve got to visit every prison. I want to visit every one and spend some time looking at it.” So over the next eight months I went down there about 10 times to do some work at every prison.

That summer, Diane and I were in Sun Valley at one of the annual conferences of the Institute for the American West. While there I met Carey McWilliams. Carey had been the editor of The Nation when I wrote for The Nation. I had never met him, but he was one of my journalistic heroes. He’s one of those old-time, left, digging news guys, you know, the guys who really go after the scoundrels.

He asked me what I was up to, and I said, “I went to death row for the first time.” Always when I went to prisons before they would say, “Do you want to see death row? Do you want to see the electric chair?” I always said no. I didn’t want to see the electric chair because I figured it was just a voyeuristic trip. I didn’t want to go to death row because I figured on death row, unlike every other place in the penitentiary, the prisoners have no mobility whatsoever. They’re put in lockdown, and I just didn’t want to come look at them like characters in a peep show.

So I always said no, but for this [tour of Texas prisons] I did go, because I wanted to look at everything. I said, “You know what, Carey, somebody should make a movie of that, it’s different from every other prison.” Death row is different from every other prison in this critical regard: Everyplace else in the penitentiary people are doing time. If you say to somebody, “What are you doing?” “I’m doing a nickel, I’m doing a dime, I’m doing a quarter.” Death row, they’re just waiting. They’re pending. Everything about the place is different.

So I said, “It’s fascinating, Carey, someone should make a movie.” He said, “Well, you should.” I said, “No, I’m a writer. Movies, you gotta work with other people. I don’t like working with other people.” He said, “You have to do it, Bruce. You’ve got the access.”

So Diane and I went down and we did this documentary called Death Row, which was broadcast on PBS stations in the US. It was broadcast in Germany; [President Francois] Mitterand used it in France as part of his campaign to get rid of France’s capital punishment, a successful campaign.

In a film people can’t say much, because it just takes too long. So Diane did much longer interviews down the hall, while I did short interviews in the cells and on the row, and we did a film and a book. The film came out in December ’79, and the book was published by Beacon in spring of ’80. The film recently came out in DVD, and it’s being distributed, so it’s out there again. And it’s going to be shown at the Albright-Knox in May.

AV: Was that the end of your prison work?

Jackson: I went to Attica sometime in the early ’80s, but it was one of those things where a guard was with me every second of the time. I could talk to no one, I could interview no one. I could go nowhere the guard didn’t want to let me go; I couldn’t bring a camera with me, and I decided, “This is worthless.”

Also, I burned out. Death row really burned me out on prisons. Death row was emotionally probably the most exhausting thing. In fact, I don’t think I’ve written anything more about prisons since then, until this last fall at a conference at UB, somebody talked me into doing a paper where I talked about the emptying out of mental institutions in the ’60s. There were literally hundreds of thousands of people. And within a few years the prisons started to grow. When I was doing my prison work in the ’60s and early ’70s, there were maybe 100,000 convicts in the United States. There are what, two and a half million now?

So I started writing about that. I told you before about how death row differs from ordinary prison: Death row operates under what I call the madhouse rules. On death row, time doesn’t count. Madhouse time doesn’t count. Death row, you’re not serving a sentence; you’re there while they decide what they’re going to do with you, whether they‘re going to execute you or cut you loose. In the madhouse, you’re not there for a sentence; you’re there until they decide what they’re going to do with you.

And then I started looking at what I call the torture gulag, the apparatus of torture the US developed in the last five or six years. Which also operates under the madhouse rules. You’re not serving time; you’re not charged with anything, in most cases. There are no rules. If you challenge a rule and it gets to a place where rules can be adjudicated, they change the rule.

So I may be doing a book about that called The Madhouse Rules. Right now I’m seeing it from the emptying of the madhouse, the burgeoning of the prisons, and the development of the torture gulag. But I may push it back to slavery, to how do you legitimize slavery in an ostensibly democratic society.

AV: What was the practical joke you learned about at that prison barbecue?

Jackson: It was either on my first or second visit to Texas. There was a field major at Ramsey, his name was Billy MacMillan. The convicts who work in the field, they’re called the line. The line goes out every day. It goes out in trucks; in those days it went out in carts, pulled by a tractor. I said, “Billy, I’d like to go out with the line on a horse. Can you get me a mild horse?” He said, “Why?” I said, “I’d like to see what it looks like from the guard’s point of view, being up there and looking down at people.”

Which was true, I did. That whole stuff about position and power. You are up on the horse looking down at guys who’re spending much of the day bending down. It utterly ratifies the power relationship. But the main reason I wanted to do it is I was a Jewish kid from Brooklyn in Texas for the first time; I wanted to ride a horse!

He said, “Yeah, I’ll give you a really mild horse, and you’ll be okay.” So I go to get on this horse. I have short legs. And my legs couldn’t quite reach the stirrups. He said, “I can’t pull these stirrups any more because it belongs to one of our guys; if I do it’ll fuck up the leather. But you’ll be all right, it’s a mild horse.”

So they’re out in the field. I’ve got a Nikon around my neck. I get on the horse, and the road I’m taking is literally a perfect, level, straight shot of a mild dirt road. Everything’s perfectly level there because they had all this slave labor to keep it level. So I ride out, and I think, I’ve got to gallop.

One of the rules of horsemanship is you do not hold on to the pommel. The pommel is for tieing your rope to when you’re roping a calf; that’s what it’s there for, it’s not for your hand.

So I kick the horse a couple of times, and the horse starts to gallop. It really felt good, because when it got in the gallop, there’s a beautiful rhythm to it. But then I started to feel insecure so I tried to get the horse to stop. And the horse didn’t want to stop. It sort of swayed. It sort of went sideways; its ass went sideways. And so I had to hold on to the pommel. Finally I’m holding onto the pommel with two hands. I had to let go of my Nikon. And my Nikon is pounding my arm, bam bam bam bam. And I’m thinking, Shit, I hope my camera doesn’t get fucked up.

I get out to the field, I’m a little sore but it’s okay. Finally the horse slows down, we’re walking. We’re out there in the field and finally Billy comes over and says, “Would you like some water?” And I say, “Yeah.” It’s hot, it’s summer, it’s Texas. So the waterboy comes over, brings me water. They literally had a waterboy. In a while he comes over and says, “Would you like some more water?” I say, “Yeah.” In a while he comes over and says, “Do you want to go piss?” I say, “Yeah, I really do want to go piss.” He says, “There’s a place over here where there’s a stump where you can get off,” because he knew about my short legs. I can get off, the problem is getting back up on the horse. So he says, “There’s a place where you can get off on the stump, you go off from the stump and go piss. It’s a good place.” So I go over there, I get off the horse, I go piss, I get back on the stump, and get back on the horse. A little while later I go back to the building. I think I understand the horse now. And I was annoyed at having lost control, so I kick it and we take off again. And again I’m insecure, I try to stop it, and again its ass is swaying and I hold on to the pommel with both hands, hope nobody’s watching, the camera pounding my arm. Finally I stop it.

There’s an old black convict sitting fencepost at the side of the road, and he watches me coming for half a mile. He just stands there with a shovel, and the horse stops right in front of him. And he says, “Say, boss, you and that horse sure ain’t in contract, is you?”

That’s 1964. Fourteen years later, I’m at the barbecue at the women’s prison in Huntsville, Texas, and there’s Billy, who says, “Bruce! I haven’t seen you for years. Remember that time I long-stirruped you and took you to the chigger patch to piss in?”

I said, “What are you talking about?”

He said—and there are about five people around us—he said, “Remember I gave you that saddle and I said we couldn’t pull the stirrups up? I knew you wouldn’t be able to stay on the horse. And I told you the horse was really calm; that horse hadn’t been rid for a month. And I took you to the chigger patch.”

That goes to part of the story I haven’t told you: That night I stopped to visit a friend of mine, who lived in Beaumont, Texas. I’m scratching. My ass itched, my ankles itched. She says, “What’s with you? Let me see.” So I pull my pants down and she says, “Holy shit. I’ve never seen anybody with as many chigger bites as you got.” What Billy had done is he had taken me to a place that was full of chiggers.

So I said to him when he told me, “Who knows this story?” He said, “Everybody.” I said, “Nobody ever told me.” He said, “It’s a better story that way, ain’t it?”

blog comments powered by Disqus

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v8n4 (week of Thursday, January 22, 2009) > Pictures From a Drawer This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue