Next story: Halloween From A to Z

An Engine Of Satan: The murder of William Morgan by Freemasons

by Buck Quigley

The murder of William Morgan by Freemasons, and the story of the martyr’s widow

Early on the morning of September 11, 1826, Lucinda Morgan began to feel that something was terribly wrong. Her husband hadn’t returned, and breakfast was getting cold. She looked at her children, two years and two months old, respectively. Hardship had been all they’d known. “What would happen to us,” she wondered, “without William.” Intuitively, she began to fear for the worst.

She had few intimate friends and no family in town that she could call on, so she went outside to look for him, leaving the children inside. It was a sunny morning in the small town of Batavia, New York, whose population at the time was around 1,200. She quietly asked a few neighbors if they’d seen her husband. As they shook their heads, her anxiety continued to rise. Finally, she met someone unafraid to tell her the truth—that several men, six perhaps, had wrestled him into a carriage and taken him away.

Lucinda was sure it was the secretive writing her husband had been up to all summer that was the reason for his disappearance, and she went home to gather up as many of his remaining papers as she could find. But what would she do with them, and who could she trust?

The next morning, shortly after breakfast, she sent for the sheriff, William R. Thompson. When he arrived, she apprised him of the situation, and asked him if he knew anything about it. He told her it was his understanding that her husband had been taken away to Canandaigua, under a charge of stealing a shirt and cravat. She looked at him hard. He finally admitted he thought the charge was merely a pretext to take him away.

Lucinda then asked the sheriff if he thought her husband could be released if she were to give up the papers she had in her possession. Thompson thought it very likely that such an exchange would gain his release, but said that he would not obligate himself in the matter. He wouldn’t go so far as to say that he should be released.

He looked at the strain etched on the young woman’s face, and said that she should go to Canandaigua herself. She should take the papers and give them to William, and if she couldn’t get to him directly, she should surrender the papers to his captors. He asked her if there was anyone in town who could accompany her on the 60-mile trip.

She asked, “Would it do for Mr. Gibbs to go?”

“No, it wouldn’t do for Horace to go, because he isn’t a Mason,” Thompson replied. “It wouldn’t do for anyone to carry you there but a Mason.”

“Horace isn’t a Mason?”

“No. Are you acquainted with Mr. Follett?”

“No.”

Thompson told her that Follett was a nice man, and a gentleman she could trust. With no other choice, she consented. Thompson left and returned a short time later, saying that Follett was unwilling to go on “a Tom fool’s errand” unless both he and Mr. Ketchum could first see the papers. Reluctant to turn over her only bargaining chip, she declined.

Thompson flared. He said it was useless, and that he would do no more to try to help her. He would not send her out to Canandaigua unless they could see the papers. She offered to let Thompson alone look at them, fearing that the others would simply take the notes away and leave her with nothing. He told her that wouldn’t do; that the others would not take his word. Reluctantly, she agreed to let them see what parts of the manuscript she’d found.

The sheriff said he would wait across the street at the Eagle Tavern—known to locals as Humphrey’s—until she had gathered them up, at which point she was to make a sign that they were ready to be viewed. Follett and Ketchum met Thompson there, and the three men waited on Humphrey’s stoop for Lucinda to give the signal. She peered from her apartment window as they spoke furtively among themselves. Looking down at her husband’s handwriting on the pages, she couldn’t believe that these words, jotted down by the solitary pen on the shabby table, could have provoked the backlash that had apparently landed him, again, in jail. She opened the door, and signaled in the direction of Humphrey’s.

How It All Began

William Morgan met and married Lucinda Pendleton in Culpepper County, Virginia, in 1819. She was the pretty, 16-year-old daughter of a Methodist minister, and he was a 45-year-old stonemason by trade, a veteran of the War of 1812. His military experience earned him promotion to captain. Two years into the marriage, he took her to York, Upper Canada (which would be incorporated as the City of Toronto in 1834), and became involved in running a brewery.

Financial difficulties soon set in, and Morgan, in a pattern that would plague him the rest of his life, found he was gaining a reputation as a deadbeat. A fire of undetermined origin burnt the brewery to the ground. He began drinking heavily, and, relying on charity, they crossed back into the United States, where he found unsteady employment as a bricklayer near Rochester. They soon settled in Batavia, in an apartment rented from a landlord named George Washington Harris.

At the time, Western New York was still very much a frontier. The Erie Canal had just opened, steady employment was hard to find, and many people managed to get by performing a patchwork of jobs, augmented by barter. Seeking to better his chances of providing for his wife and family, Morgan sought acceptance into the Fraternity of Freemasons, an organization with which he’d apparently had some involvement as a younger man in Virginia. On May 31, 1825, records show he was received into the York Rite Royal Arch Degree at Leroy—although, years later, even this scrap of evidence would be questioned by some Masonic writers.

Within a year, a new Masonic chapter was opened in his new hometown of Batavia. Morgan signed the petition seeking inclusion in the new group. However, the other petitioners in Batavia blackballed him, citing his intemperance and lack of appropriate character. Considering the drinking habits of the vast majority of the population in 1826, including Masons, this slight stung him deeply. One more avenue had been closed to him, and his hungry wife and children were constant reminders of his inability to get by on his own in a place where they were regarded as outsiders.

The Publisher

David Cade Miller was the editor and publisher of a local Batavia newspaper, the Republican Advocate. Although he’d been there since the paper’s inception 15 years earlier, by 1826 Miller too was in strained financial circumstances. Together, he and Morgan began discussing a project that would make them both targets of the secret society of Freemasons.

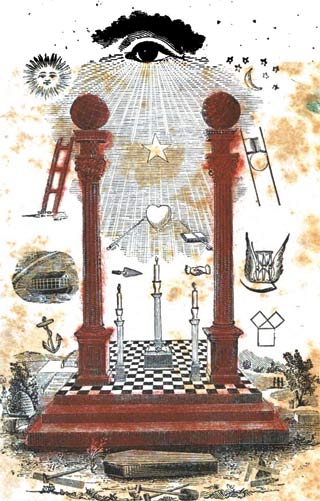

Their plan was to publish a book that would expose the fraternity as a nefarious organization whose internal allegiances took precedence over the laws that governed the rest of society. As with any group that conducts its activities in the shadows, there was already suspicion among the uninitiated. Thus, it made sense that a curious public might find such an exposé excellent reading. To Miller, it seemed a profitable gamble, and it’s said he offered Morgan the impossible sum of $500,000 to write it. They entered into an agreement to produce Morgan’s Illustrations of Masonry.

Soon, word of their plan spread within the community at large, and it caused a considerable amount of alarm among the Fraternity—particularly those who held their secret oaths in the highest regard. And because the book itself was still just a rumor, many of the initiated allowed their imaginations to run wild. Some within the group agreed that the publication of such a work should be stopped by any means necessary.

Proof of the antagonism toward Morgan is evidenced by the following advertisement taken out by the Master of the Canandaigua Lodge named Nicholas Chesebro, first in a local paper on August 9, 1826, and reprinted in many others throughout the region:

NOTICE AND CAUTION

If a man calling himself William Morgan should intrude himself on the Community they should be on their guard, particularly the Masonic Fraternity. Morgan was in this village in May last, and his conduct while here and elsewhere calls forth this notice. Any information in relation to Morgan can be obtained by calling at the Masonic Hall in this village. Brethren and Companions are particularly requested to observe, mark and govern themselves accordingly.

Morgan is considered a swindler and a dangerous man.

There are people in this village who would be happy to see this Captain Morgan.

As the communities buzzed with speculation, Miller continued to print announcements of the upcoming publication of the work, even though his paper was suffering as Masons stopped advertising in, and purchasing, the Republican Advocate. At this point, a man named Daniel Johns entered the picture. A fur-trader, Johns ingratiated himself to Miller and offered to furnish whatever money might be needed to complete the publication.

Johns, it was soon revealed, was himself a Freemason, and was able to obtain a great deal of the manuscript, which he then turned over to the General Grand Chapter of Royal Arch Masons.

Whether they’d been made aware of this or not, it was apparently not enough for a group of Batavia Masons who had Morgan arrested on a civil charge on Saturday, August 19, at a room in Rochester where he’d been sequestered to work on the book. They held him on bail until the constable and those with him—all members of the Fraternity—had also traveled to his boarding house in Batavia, where they took a small trunk full of his papers. He was released on Monday, August 20, and promptly resumed writing, as he was bound by contract to do.

The Masons discovered that their search and seizure had yielded only tangential bits of information about Morgan’s book, and they refocused their sights on Miller’s printing office, where they believed the bulk of the treacherous manuscript to be.

The Masonic Governor Weighs In

As concern spread among members of the Fraternity, advice was sought from Dewitt Clinton, then governor of New York, who is today most famous for serving as the state’s top elected official at the opening of the Erie Canal, which was nicknamed “Clinton’s Ditch.” The Governor had served as Grand Master of New York Masons from 1806 to 1820, and was, in 1826, elected General Grand Master of the General Grand Encampment of the United States—making him the country’s highest-ranked Mason.

Clinton, a skillful politician, had privately taken issue with the advertisement Chesebro had placed attacking Morgan. He’d proudly flaunted his Masonic credentials his entire political career, as a member of the elite Fraternity that counted George Washington and Benjamin Franklin among its members. But for a number of years he’d been of the opinion that members of the Western New York lodges were “growing too fast,” and that some calamity was possible if these provincial members didn’t rein in their passions. Now, with public suspicion of the Order building, he feared that Anti-Masonic sentiment could become ammunition for his political enemies.

In early August, John Whitney, a prominent Rochester Mason, traveled to Albany and met late into the night with the governor, who it is said proposed a plan to discreetly handle the awkward Morgan situation, warning that “no steps must be taken that would conflict with a citizen’s duty to the law.”

He then advised the purchase of Morgan’s manuscripts, along with his subsequent removal to a foreign country where he would be separated from Miller. To achieve this end, Clinton is said to have promised $1,000 if needed, and further promised Whitney that “he might depend upon being sustained in all lawful proceedings by the Masonic authorities of the State.”

Two Botched Crimes

Late on the night of September 8, a group of perhaps 40 or 50 Masons from all over Western New York convened in a tavern run by James Ganson in Stafford, six miles outside Batavia. Here the Brethren, likely fueled by drink, conspired to break into the printing office of the Republican Advocate to steal all the printed sheets of the book that they could find.

Because of disagreements among the conspirators, the scheme fell apart, but two nights later, Miller’s office was discovered to be on fire. John Mann, a blacksmith from Buffalo, testified on February 21, 1827, that he had been approached to participate in the arson by a man named Richard Howard, a bookbinder by trade, also from Buffalo. While riding together, Howard asked Mann if he could obtain a keg of spirits of turpentine “to destroy [Miller’s office] for the purpose of suppressing a publication, which he said Morgan and Miller were about making, relating to Free Masonry.” Mann testified that he had no money to help out with the plan.

Later, after reports of the actual fire circulated, Howard told Mann that he had, “with others who aided and assisted him, attempted to burn said office—that he had called at a store west of Batavia and bought a broom or brush to spread the turpentine with, and with his dark lantern had set fire to it; that the fire was lighted up, and he ran off; that some person ran after him, and he supposed was about to overtake him, when he turned and dashed his dark lantern into his face, which stopped the pursuit. That upon reflection since, he concluded that it was a friend who ran after him, but had never found out.”

Mann further testified that he believed it was Howard’s intention to implicate him in the crime.

Miller’s building sustained minimal damage. There is no record of the extent of the injury to Howard’s friend’s face.

Following the Sign

After Sheriff Thompson, Follett, and Ketchum saw Lucinda motioning to them from her apartment, they left the front stoop at the Eagle Tavern and crossed the street to examine the papers she’d collected. Thompson introduced her to his fellow Masons, and after looking at the work for a short time, he asked her if she was ready to go, saying Follett was ready to take her to Canandaigua. Follett then took the papers home to look them over, telling Ketchum to come by with Lucinda and pick him up at his front gate with the wagon.

About four o’clock on Tuesday afternoon, they finally started off from Batavia, only to stop a few miles down the road at a house in Stafford. They took her into a back room and were joined by two other men—Daniel Johns and James Ganson—“who immediately proceeded to examine the papers with much earnestness, and held much low conversation with themselves in under voices.”

According to Lucinda’s sworn statement of September 22, 1826, Johns was asked if these were the papers he’d seen in the office when he was there. Johns then folded some of the papers to display which ones he’d seen before. Finally, after much whispering, Follett turned to Lucinda and told her he wouldn’t be taking her to Canandaigua, after all.

He explained that Mr. Ketchum was going to Rochester, and would be willing to take her to see her husband. He said that although he wasn’t much acquainted with Ketchum, he took him to be a gentleman. Ketchum assured her he was a gentleman, and that she needn’t be afraid to trust herself with him. Then Ketchum took the papers, tied them up in his handkerchief, and climbed into the wagon. Lucinda followed, and Johns hopped in as well. The three rode as far as LeRoy, where Johns got out, saying he hoped to see Ketchum in a couple of days. Ketchum and Lucinda traveled another 14 miles to Avon, where they stopped for the night.

The next morning—Wednesday—they started the remaining 25 miles to Canandaigua. They arrived around noon and stopped at a tavern on the main street. Ketchum then appears to have asked around about William, with little success. He asked Lucinda for the papers, and left her there, promising to go and find out everything he could about her husband’s current circumstances. It was already dinner time.

Shortly before nightfall, Ketchum returned to tell her what he’d learned. William had been tried for stealing a shirt, only to be thrown back in jail for a two-dollar debt. A man from Pennsylvania had then appeared, saying he had a warrant for William for a debt he owed there. This man paid the two-dollar debt and took William in a private carriage to Pennsylvania Tuesday night to face charges there. William was no longer in Canandaigua, he said, and when would she like to go back to Batavia?

Lucinda, having missed the chance to visit her husband by a full day, and being 60 miles away from her toddler and two-month-old, burst into tears.

Worse still, though she didn’t know it yet, the Pennsylvania story was a lie.

The Jailer’s Wife’s Tale

Mary Hall was the wife of Israel Hall, the keeper of the jail for Ontario County, New York, at Canandaigua. They lived in the jail with their children, and Mary was often responsible for the prisoners whenever Israel was gone. On September 12, he stepped out around seven in the evening, and shortly thereafter a man named Loton Lawson arrived. Lawson asked to see Mr. Hall. Mary told him he was not at home, and she didn’t know where he had gone.

Lawson told her he wanted to see Morgan, the prisoner who had been brought in the evening before on the criminal charge of stealing a shirt and cravat. That charge was quickly dismissed when no witnesses appeared against him. The moment he was released on that charge, however, Morgan was arrested again on the civil charge of owing $2.68 to a man named Aaron Ackley—a debt that was transferred to Nicholas Chesebro, the man who had taken out the newspaper ad cautioning the community about Morgan. Morgan had offered his coat as settlement of the debt, but his offer was refused, and he was locked in the cage.

Now, a day later, Lawson asked to have a few words with Morgan. Mary Hall refused. She said that it was against the rules of the jail, and that nothing could be said to the prisoner without her hearing them also. Lawson pressed for privacy. Mary asked Lawson who he was. Lawson said he was there to pay off Morgan’s debt, and asked the prisoner if he would go home with him. Morgan agreed, acknowledging that Lawson was a neighbor.

Lawson said he was tired and would just as soon take him out of the jail that night, so he went out to look for Mr. Hall. He returned in half an hour, saying he’d looked in the hotel and everywhere else with no success. He asked Mary if he could just pay off the debt and take Morgan, but she refused, saying she didn’t know the amount of the debt. He assured her it was a small sum, and offered five dollars to cover it, saying he was sure it was more than enough. Mary said it was her understanding that “Morgan was a rogue, and that she did not like to liberate a rogue; that she understood great pains had been taken to secure Morgan, and that the public or individuals were interested in having him kept secure; that what she should do would be considered the same as if it had been done by her husband, and if she should discharge Morgan, she was afraid her husband would be blamed.”

Lawson told her that if Mr. Hall were there he would surely release the prisoner. Further, Lawson gave his word that he would pledge a hundred dollars that her husband would not be injured or blamed if she would release Morgan. Mary refused, saying she cared more about public opinion than money.

“What if Colonel Sawyer says you may safely release him?” Lawson asked.

“I don’t know Colonel Sawyer any better than I know you,” Mary replied, “and besides, Colonel Sawyer is not the plaintiff in the execution upon which the prisoner is committed. He has nothing to do with it.”

Nevertheless, Lawson left to fetch Colonel Sawyer. He returned in just a few minutes with Sawyer, who must have been standing outside with some of the others. The colonel requested Morgan’s release, making the same promises as Lawson, that her husband would not be held accountable if she let Morgan go.

Mary said she didn’t want to keep a man in jail who ought to be let out, but that she was still not about to release the sort of rogue she understood Morgan to be. Both men were now exasperated.

“The debt for which he’s held has been assigned to Nicholas Chesebro,” Lawson finally said. “Let’s go find Chesebro.” With that, Lawson and Sawyer turned and walked to the door, followed by Mary. There, they saw two men approaching the jail. Lawson hurried out to greet them, and after a brief conversation, one of the men continued up to the door of the jailhouse, where Mary and Sawyer were still standing. The man who approached was Nicholas Chesebro.

Chesebro was the coroner of Ontario County, and as such, a recognized figure in the community. He assured Mary that he had bought the debt held on Morgan, and that if these men wanted to pay the debt he had no problem with the prisoner being released. Lawson laid the money on the table as Mary fetched the keys and started walking back to release Morgan. Lawson called out for her to wait, that he wanted to go along, and he quickly went to the door of the jailhouse and let out a loud whistle before hurrying back to accompany her.

When they reached the hall outside Morgan’s cell, Lawson told him to hurry and get dressed. He did, and Lawson took him by the arm as Mary opened the door. When she unlocked the second door, Lawson hurried Morgan through and led him straight outside. As she was refastening the lock, she testified that she heard outside the jail “a most distressing cry of murder.”

Spirited Away

Mary ran to the door and saw Lawson and a man named Foster holding Morgan tightly by the arms. “Morgan continued to scream or cry in the most distressing manner,” she later testified, “at the same time struggling with all his strength, apparently, to get loose from Lawson and Foster; that the cry of Morgan continued till his voice appeared to be suppressed by something put over his mouth; that during the time that Morgan was struggling, and crying murder, the said Col. Sawyer, and the said Chesebro, were standing at a short distance from the jail door, near the well, and in full view and hearing of all that passed, but offered no assistance to Morgan, nor did they attempt to release him from Lawson and Foster; but one of them struck with a stick a violent blow upon the well curb, or a tub, standing near.”

Immediately after the sound was struck, a carriage appeared. It being a full moon, she could plainly see the gray horses pulling the carriage, and watched as Sawyer and Chesebro followed behind, offering no help to the struggling man except to pick up his hat and carry it into the carriage. Then they were off.

Mary’s account was corroborated by several other witnesses. Among them:

Daniel Tallmadge, who was a fellow prisoner at the time. Upon his incarceration, Morgan asked Tallmadge if the jailer was a Mason. Morgan said he would fare poorly if that were the case. Later, speaking of his impending release, he confided to Tallmadge that if Lawson turned out to be a traitor, he was a dead man. Morgan did not fully trust Lawson, but decided he would go with him in order to be released. Tallmadge also heard the cry of murder three or four times till it appeared to be suppressed.

Martha Davis, who lived opposite the jail. Davis said she saw eight to 10 men gathered around outside the jail on the evening of September 12. She recognized Sawyer, Chesebro, and a man named Chauncey Coe. She tried talking to Chesebro, whom she knew, but he did not respond. She went inside and told her husband that “something was going on about the jail which was not right.” About nine o’clock, she heard the doors of the jail being opened. She looked and saw some men at the jail door, heard a cry of murder, observed the ensuing scuffle, heard the rap on the well curb. She saw two men rushing from near her house toward the jailhouse door, and said the cries of murder seemed to be surpressed with something over the victim’s mouth, and that occasionally the cries seemed to break free in an inarticulate sound indicating great distress. She then saw the two grey horses and a carriage she thought were owned by a Mr. Hubbard—who kept horses and carriages to let—galloping down the street.

Seth Osborne, who testified that he went to the door of his house around nine o’clock and “saw some men a few rods from his door; that one of the men appeared to be partly down and struggling, and making a faint noise of distress; that he went towards the men, one of whom was a little behind the rest, and he asked them what was the matter?” Colonel Sawyer answered him, “Nothing, only a man has been let out of jail, and been taken on a warrant, and is going to have his trial.”

It later came out that the night before, right after Morgan’s incarceration, and during the day of his abduction, various conferences were held among the Masonic Brethren in Canandaigua. Loton Lawson had been sent to John Whitney in Rochester, and to see some other Brothers in Victor. The purpose of his visits was to arrange for relays of horses and drivers along the 125-mile route from Canandaigua to Fort Niagara, north of Lewiston.

The Stations of the Double-cross

The kidnappers moved into the night, stopping occasionally to feed and water the horses, or to change wagons, teams, and drivers. They traveled northwest to Victor, on to Rochester, and then westward along the Ridge Road that ran along the Niagara escarpment toward Lewiston. At about eight o’clock on the morning of September 13, at Hanford’s Tavern, four miles outside Rochester, a man named Ezra Platt furnished a new carriage and a man named Orson Parkhurst took the reins. Hiram Hubbard’s horses and wagon turned back toward Canandaigua.

Twenty miles further, around noon, Isaac Allen, a farmer, lent a fresh pair of horses. A mile west of Gaines, they stopped at the home of Elihu Mather, who fed the party and lent a pair of his brother’s horses, getting on the box to drive as Parkhurst headed back toward Rochester. They then stopped at Murdoch’s Tavern, watered the horses, and “took drinks all around.”

Ten miles further on, at Ridgeway, they met Jeremiah Brown, who hitched up his own fresh horses and hopped on the box with Mather. They rode on another 10 miles to Wright’s Corners, where there was another tavern, arriving around sunset. Here a Mason named Eli Bruce joined them, and stayed with the party all the way to Fort Niagara. Bruce was the sheriff of Niagara County.

They stayed a while at the Wright’s Corners tavern, then continued on another six miles to Molyneux’s Tavern in Cambria. Here, another change of horses was made, and a man named Jeremiah Brown drove the rest of the way to Lewiston. That night, it so happened that a large number of Freemasons from around the entire region were gathered to mark the installation of the Royal Arch Chapter at Lewiston.

Late that night, Bruce went with a stage proprietor named Samuel Barton to his office to see what driver could be found to take him up to Youngstown. A man named Corydon Fox was called, and directed to take a carriage over to the Frontier House (which still stands today at 460 Center Street), where Bruce met him and directed him to a back street.

There, two men got out of a carriage and climbed into Fox’s carriage. It was a dark, but Fox said he saw one man being held by the arm. Bruce ordered him to drive to Youngstown, where they stopped in front of Colonel King’s house. Bruce went in for about 15 minutes, at which point he and King rejoined those in the carriage. Fox heard a voice inside the carriage pleading for water. Bruce replied that he would have some soon.

Fox drove on toward Fort Niagara, where he was ordered to stop at the graveyard. There, his passengers disembarked, four in all, with one apparently being assisted, as before. Bruce told Fox to go back to Lewiston. As he turned the carriage around, he saw the group starting off in a tight group toward the fort.

Later, Bruce would be criticized by some Masons for letting Fox, a non-Mason, drive the final leg of the journey.

The Magazine

From 1826 to 1828, Fort Niagara was deactivated as an outpost of the American Army. During that time, the entire complex was left under the watch of one Edward Giddings, a Mason. A more secure private prison would be hard to imagine. Inside the fort, the magazine used to store ammunition was described by Giddings himself as a building “built of stone, about the height of a common two story building, and measures about fifty by thirty feet on the ground…There is but one door, around which there is a small entry, to which there is a door also. There are no windows or apertures in the walls, except a small ventilator for the admission of air, and one small window in each end about ten feet from the ground—they are usually kept closed, and locked on the outside with a padlock—these shutters are made of plank, covered with sheet iron—the floor is laid with plank, pinned to the sleepers with wood pins.”

This was Morgan’s final jail cell. What happened to him after his arrival there is the stuff of wild speculation. Masonic writers insist that he was taken from there across the lower Niagara River in the rowboat ferry operated by Giddings, docked in the water at the base of the fort. Once in Canada, he was given money and his freedom, provided he never return to the US.

Many of these writers argue that Morgan was a willing participant in his own kidnapping. Feeling trapped and betrayed by his publisher, Miller, he wanted nothing more than to escape from him and his contract to finish the book on the Freemasons. The only way this could be accomplished was to go along with the protracted kidnapping, which was witnessed by so many, and escape to a foreign land. If he went along, they’d promised him $500 to start anew. This story lines up with the plan allegedly put forward by Governor Dewitt Clinton.

Those committed to promoting this theory say that Morgan traveled north and eventually signed on as a seaman with the British Navy. From there, he was either marooned on a tropical island, or made it as far as Smyrna, in Turkey, where he lived to a ripe old age. Another version of his life had him passed along by Freemasons until he escaped and joined a band of Apache Indians in Texas. There, he married the chief’s bride and eventually became chief himself. Another has him forced to enlist in the British Navy, where he eventually landed in Australia, started a newspaper called the Advertiser, married a beautiful woman, and became rich. Still another had him living the happy life of a hermit it the most remote reaches of northern Maine. In all these versions, he ended his life a happy man.

However, these versions must be balanced with the fact that his wife and children neither saw nor heard from him again after the morning of September 11, 1926.

The Early Fallout

In the vacuum of Morgan’s absence, feelings quickly began to run high that he had met an unpleasant end. Miller finally did publish Morgan’s book, and it apparently sold very well, though not well enough to generate the astronomical sums he’d led Morgan to expect. Much of the sales were attributed to the mystery of his disappearance.

Charges were brought against many of the men involved in Morgan’s disappearance, and several trials were conducted. Among the first found guilty were Loton Lawson and Nicholas Chesebro, who were each given two years by Judge Enos T. Throop not long after the incident.

Eli Bruce, the Niagara County sheriff who’d facilitated Morgan’s transport from Lockport to Fort Niagara, had a particularly tough time of it, first being stripped of the sheriff’s office by Governor Clinton in September 1827, and then being found guilty in August 1828 for his role in the conspiracy. He was sentenced to two years, four months, and stoically served his time before leaving prison a broken, sickly man. He died two years later of cholera, and was viewed by many Masons a martyr.

Throop, in his early sentencing of Lawson and Chesebro, spoke of the growing Anti-Masonry movement as a “blessed spirit” that he hoped “would not rest until every man implicated in the abduction of Morgan was tried, convicted and punished.” Throop would go on to join Martin Van Buren’s gubernatorial ticket, running for lieutenant governor of New York State in 1828, in the election that followed the death of DeWitt Clinton in February of that year. After his eclection, Van Buren was named to Andrew Jackson’s cabinet, making Throop the governor of New York in March 1829. Thus, Clinton, who’d been so concerned about Anti-Masonic backlash during his lifetime, was almost immediately replaced after his death by a man who promoted Anti-Masonic beliefs.

In 1828, the Anti-Masonic Party was formed in Upstate New York. It was the first single-issue political party in the country, riding on the strength of church congregations and mass meetings where citizens resolved not to elect any Mason to political office, based on the belief that such a person’s ties to the secret society would supercede the interests of the rest of the population. The movement was further fueled, in 1829, by a collection of materials compiled by a former Mason called Elder David Bernard, who broke with the Craft along with other Brothers at a convention of seceding Masons in LeRoy in 1828. The preface of his book, Light on Masonry, describes how he “was led to investigate the subject; found it wholly corrupt; its morality, a shadow; its bevevolence, selfishness; its religion, infidelity; and that as a system it was an engine of Satan, calculated to enslave the children of men, and pour contempt on the Most High.”

The flames of the movement grew, fanned by political writers and provocateurs like Thurlow Weed, who was perhaps more responsible than anyone for keeping Morgan’s story alive and casting him as a martyr. So strong was the resentment that a majority of Masonic lodges in many parts of the Northeast were forced to close their doors due to dwindling memberships. Although its heyday was short-lived, the Anti-Masonic Party was the first to hold conventions, whereby local delegates pledged their votes to state candidates as a way of building consensus—which is the model major political parties use to this day.

Other Morgans

About a year after Morgan’s disappearance, a decomposed body was found near the mouth of Oak Orchard Creek on the shore of Lake Ontario, and buried in a crude casket near the water’s edge. As news of the discovery circulated, there was a call for an inquest to see if it could be the vanished man’s remains. Lucinda was called and asked to provide a detailed description of her husband, including any identifying marks, prior to the grave being opened.

She described what he’d been wearing the morning of his disappearance, the color of his hair, a scar on his foot, and also noted another odd feature—a double row of teeth on both top and bottom. A doctor familiar with Morgan confirmed this abnormality, and also stated that one of his teeth had been extracted, and that another was broken.

When the coffin was opened before 40 people in attendance, the corpse was found to share all these peculiarities. The only differnce was what was left of his outfit. The body was unanimously declared that of William Morgan, and was taken to the cemetery in Batavia for burial.

It was not long in the ground, however, before news of the event reached Canada and the wife of a man named Timothy Monroe. Monroe had drowned in the lower Niagara River, and also had a double row of teeth. The body was dug up again, and while she knew nothing of the extracted or broken teeth, Mrs. Monroe accurately described the clothing, down to a different colored piece of yarn used to mend a sock. The hair didn’t match, nor did the man’s height, but on the strength of her detailed description of the dead man’s apparel, the body was concluded to be that of Timothy Monroe.

Over the years, other bodies would be discovered and thought to be Morgan, but his actual, undeniable remains were never found. No corpus delicti, no case for murder.

However, just as there were stories of Morgan’s happy afterlife in far-flung lands, there were also several dramatic descriptions of his gruesome demise, often he deathbed confessions of men whose consciences could no longer contain the guilt they’d harbored for years. The most famous of these was allegedly dictated to Dr. John L. Emery, or Racine County, Wisconsin, in the summer of 1848, from the dying lips of Henry L. Valance, who claimed to be involved in Morgan’s murder. Here is an excerpt of Emery’s account, published after Valance’s death, describing the events of 22 years earlier:

Many consultations were held, many plans proposed and discussed, and rejected. At length being driven to the necessity of doing something immediately for fear of being exposed, it was resolved in a council of eight, that he must die: must be consigned to a confinement from which there is no possibility of escape—THE GRAVE. Three of us were to be selected by ballot to execute the deed. Eight pieces of paper were procured, five of which were to remain blank, while the letter D was written on the others. These pieces of paper were placed in a large box, from which each man was to draw one at the same moment. After drawing we were all to separate, without looking at the paper that each held in his hand. So soon as we had arrived at certain distances from the place of rendezvous, the tickets were to be examined, and those who held blanks were to return instantly to their homes; and those who should hold marked tickets were to proceed to the fort at midnight, and there put Morgan to death, in such a manner as should seem to themselves most fitting.

Valance, of course, had drawn a slip of paper with a D on it. His role was to go into the magazine and tell Morgan his fate, while the other two were to gather the ropes and weights that would sink him below the waves.

Morgan, on being informed of their proceedings against him, demanded by what authority they had condemned him, and who were his judges. He commenced wringing his hands, and talking of his wife and children, the recollections of whom, in that awful hour, terribly affected him. His wife, he said was young and inexperienced, and his children were but infants; what would become of them were he cut off; and they even ignorant of his fate?

They gave him one half hour to prepare for his death. They left him in the magazine, where everything remained as “quiet as the tomb within.” Then they entered, laid hold of him, bound his hands behind, and placed a gag in his mouth.

A short time brought us to the boat, and we all entered it—Morgan being placed in the bow with myself, along side of him. My comrades took the oars, and the boat was rapidly forced out into the river. The night was pitch dark…Having reached a proper distance from the shore, the oarsmen ceased their labors. The weights were all secured together by a strong cord, and another cord of equal strength, and of several yards in length, proceeded from that. This cord I took in my hand [did not that hand tremble?] and fastened it around the body of Morgan, just above his hips, using all my skill to make it fast…Then, in a whisper, I bade the unhappy man to stand up, and after a momentary hesitation he complied with my order. He stood close to the head of the boat, and there was just length enough of rope from his person to the weights to prevent any strain, while he was standing. I then requested one of my associates to assist me in lifting the weights from the bottom to the side of the boat, while the other steadied her from the stern…as Morgan was standing with his back toward me, I approached him, and gave him a strong push with both my hands, which were placed on the middle of his back. He fell forward, carrying the weights with him, and the waters closed over the mass. We remained quiet for two or three minutes, when my companions, without saying a word, resumed their places, and rowed the boat to the place from which they had taken it.

The First 9/11 Monument

Today, in beautiful old Batavia Cemetery, one can visit a 35-foot-tall monument capped by a statue of William Morgan. It was erected on September 11, 1882, by the National Christian Association. The dedication ceremony was attended by many, including more than 200 delegates from the NCA, whose scathing speeches against the evils of Masonry were calmly heard by several members of nearby Masonic lodges, who also attended the event. While it doesn’t mark the final resting place of Morgan, since his body, like his fate, were never truly discovered, the inscription on its base surely reads like a memorial to the hero of a cause, who disappeared from Batavia September 11, 1826:

Sacred to the memory of Wm. Morgan, a native of Virginia, a Capt. in the War of 1812, a respectable citizen of Batavia, and a martyr to the freedom of writing, printing and speaking the truth. He was abducted from near this spot in the year 1826, by Freemasons and murdered for revealing the secrets of their order. The court records of Genesee County, and the files of the Batavia Advocate, kept in the Recorders office contain the history of the events that caused the erection of this monument.

Morgan’s story seems doomed to drift in and out of public consciousness. As far back as 1833, John Quincy Adams, the sixth president of the United States, lamented this in a letter to W. L. Stone:

Perhaps the most remarkable evidence of the binding force of Masonic obligations and of the real power of the fraternity, is afforded in the conduct of those who control the newspapers of the country. When the English forger, Stephenson, was kidnapped in a distant state, and brought forcibly to New York, the whole country rang with the alarm which was sounded by the newspapers and every patriot was called on to resent this invasion of personal liberty.

But when a free citizen of America was dragged from his family, forcibly carried through the country and drowned in the deep waters of the Niagara, a death-like silence pervaded the newspapers; or if they spoke, it was to notice the outrage in terms of irony and as a trifling and unimportant affair. The papers of every party teemed with the most gross misrepresentations; a simultaneous attack was made on all who were engaged in discovering the offenders’ fabricated accounts of Morgan having been seen at different and distant places were incessantly circulated, and every effort was made to delude the public and mislead inquiry.

How tremendously powerful must have been that organization, which could produce this shameful treachery of the press to it’s public duties! These facts are as notorious as the sun at noon-day, and a stronger proof of their general truth cannot be adduced, than the single circumstance, that to this day, thousands and millions of reading citizens of this country are ignorant of the history of Morgan’s abduction and murder, and are totally uninformed of the abominations of freemasonry.

The Widow of the Martyrs

Four years after Morgan disappeared, his wife Lucinda remarried. This was a disappointment to Anti-Masons, who saw her as a useful symbol—the poor widow of their martyr. However, she’d been living solely on charity to raise her children, and when a Batavia silversmith, her landlord, George Washington Harris, proposed, she accepted, and they were wed on November 23, 1830. Soon thereafter, they left town for good.

By 1834, they were living in Terre Haute, Indiana. It was there that they became Mormons, baptized by the Apostle Orson Pratt, who was on a missionary journey between Clay County, Missouri, and Kirtland, Ohio. The Latter Day Saints movement had begun just east of Rochester, in Palmyra, when Joseph Smith was directed by visions of the angel Moroni to a long-lost book inscribed on golden plates that were God’s record of his dealings with his chosen ones in America. By 1837, George and Lucinda had relocated and were living in the Mormon settlement of Far West, Missouri.

In Far West, most likely that fall, during a visit by Joseph Smith, Lucinda was taken as one of the Prophet’s early wives.

The Harrises began to ascend within the hierarchy of the Saints. On September 2, 1838, Patriarch Joseph Smith Senior, the father of the Prophet, blessed George, Lucinda, and William Morgan’s children Lucinda Wesley Morgan and Tomas Jefferson Morgan. But soon the Mormons were driven from Missouri, and the family moved with to Nauvoo, Illinois, into a house directly across the street from the Prophet himself.

By 1844, public opinion in Nauvoo was swinging against the Mormons. As in other places, polygamy was viewed as a problem. Smith, now the mayor of Nauvoo, closed the offices of a local paper, the Nauvoo Expositor, for printing that he was polygamist who had established a political Kingdom of God on Earth.

Joseph Smith and his elder brother Hyrum made the unfortunate decision to travel to Carthage, Illinois, where they were charged with treason and incarcerated. An angry mob rushed the prison. While attempting to barricade the door, Hyrum was shot and killed. Joseph stood in the window, where he cried out to God and was also shot and martyred.

Lucinda was seen at Joseph Smith’s funeral. As two of his wives were prostrate on the floor, wailing over his death, she was said to be standing at the head of his casket. Her face was partly hidden behind a veil, as “her whole frame convulsed with weeping.”

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v8n43 (Week of Thursday, October 22th) > An Engine Of Satan: The murder of William Morgan by Freemasons This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue