Brad Fraser's True Love Lies Premieres at BUA

by Anthony Chase

Brad Fraser, author of Love and Human Remains and Poor Super Man, is arguably the most important Canadian playwright of the past 20 years. This week, Buffalo United Artists opens the American premiere of his newest play, True Love Lies, in which a man finds his marriage and his life turned upside down when his daughter uncovers a secret from his sexual past. The play has already been seen in Manchester, England and in Toronto.

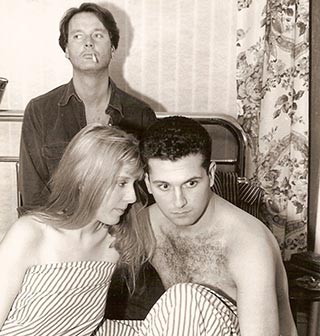

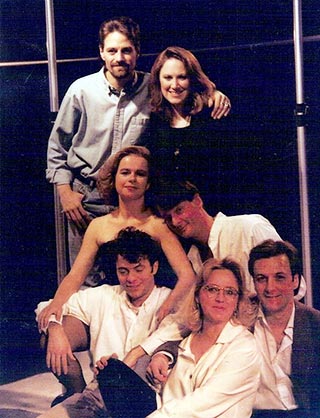

It is not surprising that a small, independent theater company in Buffalo, New York should host the American premiere of a work by such a prominent writer. Fraser has long held special importance for BUA. They staged his landmark work, Love and Human Remains, in 1993 to resounding success and a critical maelstrom; they restaged it a few years later, and along the way produced his plays, Poor Super Man, The Ugly Man, and Martin Yesterday. At one point, BUA even hosted a “Fraser Fest” featuring his work in rotating repertory.

In many ways, Fraser’s Love and Human Remains defined BUA. Their first experience with his work drew a line in the sand, signaling that the company was answerable only to its own artistic ideals and to audiences that supported them.

Brad Fraser and BUA both arrived on the theater scene at a significant cultural moment. Fraser was among the first major playwrights exploring gay themes who did not feel the need to negotiate with heterosexual audiences for approval. Earlier landmark plays like Tennessee Williams’ Suddenly Last Summer or Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band worked to assert the existence of gay people, or to argue for their acceptance. For Fraser—writing just before plays like Rent, Avenue Q, and Love! Valour! Compassion!; just before television shows like Queer as Folk and Will and Grace; just before British “In-Yer-Face” drama and the work of Mark Ravenhill—gay people and sexual ambiguity were always simple facts of life. He never “came out,” because he was never in hiding. Fraser is interested neither to curry acceptance nor favor. He strives solely to entertain and challenge audiences that are entirely comfortable with the LGBT experience—whatever their personal histories.

As it happens, this is the story of BUA, too. In fact, the founders of BUA were startled when they first saw themselves identified as a “gay theater” in the press. Their offerings always included a variety of genres, beginning with the feminist revue A…My Name is Alice, and including Noël Coward’s Blithe Spirit, Somerset Maugham’s The Constant Wife, Federico Garcia Lorca’s House of Bernarda Alba—none gay themed (though most of the playwrights were gay, come to think of it). Their interest in gay-themed work was not a political statement, and not all members of the company are gay. Sexual diversity is simply a part of their daily norm.

Fraser’s plays have spoken profoundly to audiences, often outside the mainstream of the theater establishment. Love and Human Remains enjoyed its initial successes in Edmonton, Alberta and in Chicago. Poor Super Man premiered in Cincinnati. Other plays have blazed trails in Manchester before London. After Love and Human Remains, Fraser has elected to ignore New York almost entirely.

Fraser is more engaged by audiences who respond to his work than to producers and critics who have often found it frightening. In characteristically undiplomatic fashion, he has said that he is not interested by the “geriatric” and affluent audiences who often dictate theatrical taste—not the audience that is looking for benign ways to kill time during that period between retirement and the grave. He aspires to engage what he sees to be a more vital audience, one raised on television and movies, but which still has an urgent desire to puzzle through life’s complexities in a way that theater does best (whatever their age). His scripts are fast-paced and make frequent references to popular culture and current events. Their structure is more like film scripting than traditional climactic dramatic structure. True Love Lies, for instance, has over 30 scenes in the first act alone—some only a few sentences long.

Of course, it is not structure, style, or even the subject matter of Fraser’s plays that has worried conformist arbiters of taste. Prudish critics of his plays (gay and straight) have always found their greatest source of anxiety in his representations of homosexual sex—or that very off-stage activity from which heterosexual audiences had been protected for so long: the horrible specter of two men kissing. Up until Fraser and his generation, homosexual desire was likely to be a tortured affair sublimated through a tragic woman in despair. A gay kiss on stage was a comic moment. Not any more!

Neither is homosexual desire in a Fraser play of the antiseptic and sentimental variety found on television and in mainstream film. Sexual orientation is an unstable quality for numerous Fraser characters. The central character of Love and Human Remains was David McMillan, a gay man fearful of emotional intimacy. He and his circle of friends took missteps as they endeavored to forge fulfilling relationships. David’s female roommate fluctuated back and forth between relationships with a woman and a man. Kane, the bus boy where David worked as a waiter, developed a crush on him, but was unwilling to commit to being gay. Bonita, a psychic prostitute, obsessed with urban legends, was available to anyone, for a price. David’s best friend, Bernie, was ostensibly heterosexual, but had bisexual impulses—he also turned out to be a serial killer. Oh, the fun of Fraser!

The play was written with great cynical humor, but was serious in tone. Fraser subverted elements of various genres to tell his story, including television situation comedy, thriller, comic books, gossip publications, soap opera, rock videos, and grade-B horror film.

These qualities also characterize the new play, True Love Lies, and characters in this play have appeared in others. Indeed, Love and Human Remains, Poor Super Man, and True Love Lies are a kind of trilogy. In True Love Lies, David McMillan, formerly a television star, an artist, and a waiter, is now a successful restaurateur in his middle age. Kane, the busboy from Love and Human Remains, also makes a return, this time as a married man with a family of his own. When Kane’s daughter applies for a job at David’s restaurant, the encounter leads to the revelation of a secret—Daddy has not always been heterosexual.

Let the games begin!

While Fraser has never needed to negotiate gay issues with his audiences, he has fought numerous battles within the entertainment industry—notably with producers, critics, and editors. He has never flinched, and even seems to delight in these controversies.

For instance, he famously writes open letters to drama critics with whom he disagrees, or who he thinks are unqualified—and to the publications that employ them. In a recent letter to the Toronto Star, Fraser criticized the paper for reviewing plays that are still in previews, and for sending a working playwright to do the job: “It’s worth remembering,” says his letter, “that theatre is indeed produced for audiences, as are newspapers, and newspaper readers, like theatre-goers, also have a right to the full story. After all, many of them do not realize that Mr. [Richard] Ouzounian is not just a mediocre theatre reviewer but is also one of Toronto’s most mediocre playwrights and directors.” Ouch!

When major film studios inquired about making the film version of Love and Human Remains, but insisted that the central character, David McMillan, should be heterosexual, because the play was neither about “coming out” nor AIDS, Fraser would not relent. In Fraser’s world, there is nothing gratuitous about a character’s sexuality. Love and Human Remains was made as an independent film. Poor Super Man was also filmed independently as Leaving Metropolis. The central character is homosexual in both films.

Fraser’s work has also inspired some spectacularly normative critical reactions. One of the most hysterical was actually here in Buffalo, where one reviewer flew into a rage over Love and Human Remains, complaining that the play did not reach out to the “non-partisan” heterosexual (read “normal”) audience, and could not, therefore, be considered art. In the same article, the reviewer expressed wariness over Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, which had opened in New York seven months before, arguing that audiences who were flocking to Brad Fraser and Tony Kushner were not true “theatrical audiences” at all, but a sociological “special interest group.” More than a decade later, that review still elicits peals of laughter for its frightened contention that Love and Human Remains was a “feeble play,” “badly written”—published just few weeks before the script won the Evening Standard Award in London, and in the very year Kushner won the Pulitzer Prize—and for its reconstruction of gay dramatic history—contending, for instance, that Joe Orton had been more tasteful and discreet than the new wave of gay writers, and that Orton would not have understood the word “gay” to mean “homosexual.” (In reality, the term “gay” meaning “homosexual” has been in common use since the 1930s.) The success of writers like Fraser and Kushner signaled that the days when the heterosexual view could be viewed as “non-partisan” or “normal” were over in the theater.

In another famous incident, the premiere of Poor Super Man at Ensemble Theatre of Cincinnati was announced, then canceled after board members got nervous over its explicit homosexual content, then reinstated after the public rallied in its support. Publicity was heightened by the fact that Cincinnati had been the site of the Robert Mapplethorpe controversy, also centered on homoeroticism, just three years previous. Wildly successful, the Cincinnati production of Poor Super Man was named one of the best plays of 1994 by TIME magazine.

In time, fearful outbursts against Fraser, reminiscent William Winter’s (1836-1917) tirades against the supposed obscenity of Ibsen and Shaw, have served to haunt the critics who leveled them and to mark their obsolescence, and have simultaneously boosted interest in Fraser’s work. Love and Human Remains is now universally regarded as a Canadian classic and (like Kushner’s play) a seminal work of dramatic literature. Fraser has become a media personality in Canada, and at one point, even hosted his own television talk show. Moreover, his influence is far-reaching. In Great Britain (where True Love Lies first opened, even before its Canadian debut in Toronto) his impact has been particularly profound. The creators of the original British Queer as Folk identified his work as an inspiration for the historic television series—making it especially ironic when the producers of the American version on Showtime invited Fraser to write for the show—which he did for its final three seasons.

True Love Lies boasts all the hallmarks of a Brad Fraser play. Here we find characters coming to terms with sexualities in flux, pasts that haunt the present, and representations of sex, drug use, and violence—all set within the paradoxically comfortable yet insecure confines of a nuclear family. Interestingly, however, the most unsettling sexual moment this time around is heterosexual. Fraser delights in the observation that his audience is very comfortable with the idea of a straight man having a gay affair—but not when things happened in reverse.

Chris Kelly, who is directing the BUA production, notes that a Fraser script involves particular challenges. Pacing must be brisk, and dramatic reversals must be accomplished at breakneck speed without lingering, sometimes within the space of a few sentences. In addition, Fraser combines moments of comedy and serious drama in a way that challenges even seasoned actors.

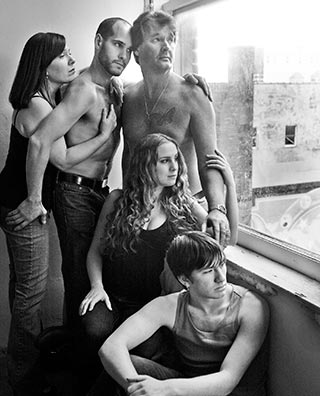

Richard Lambert, who played David McMillan in BUA’s 1993 production and again in Poor Super Man in 1994 (winning an Artie Award for his performance), gets his third shot at the character in this production of True Love Lies. (McMillan has aged along with his creator, Brad Fraser, who recently turned 50.) Kurt Guba plays McMillan’s former lover, the now married father of two, Kane. Guba’s real-life wife, Wendy Hall, plays his spouse. Their children are played by Cassie Gorniewicz and R.J. Voltz. True Love Lies opens on Friday, January 8, at the BUA Theater of Chippewa Street. Call 886-9239 for ticket information.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n1 (week of Thursday, January 7) > Brad Fraser's True Love Lies Premieres at BUA This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue