The Rust Belt's Unfinished Business

by Bruce Fisher

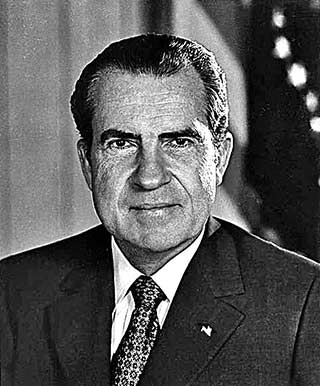

How Nixon’s Supreme Court screwed the North out of metro schools and left us all poorer

Racism, institutionalized by the bent politicians whom Richard Nixon appointed to the United States Supreme Court, hastened the demise of the Great Lakes cities, and only metropolitan-wide school reorganization offers any hope of fixing what is so terribly broken.

That’s the gist of a new book—Hope and Despair in the American City by Gerald Grant (Harvard University Press 2009)—that compares the sorry recent history of Syracuse, New York with the glad success of Raleigh, North Carolina. One town tried desegregation within the boundaries of the old city and failed, and is dying, while the other town regionalized schools, and has been growing by leaps and bounds.

You don’t have to be a scholar to figure this out. As the unreconstructed free-market fundamentalist L. Gordon Crovitz wrote recently in his Wall Street Journal column, watch what crowds do, because they tend to make better decisions than individuals. Crowds of investors, job-creators, and regular folks, too, have been fleeing Rust Belt cities and heading to metro areas like Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina, where the city and county school districts have been unified for decades.

City and suburb in the North Carolina cities of Raleigh, Durham, and Charlotte all got unified school management in the 1970s and 1980s. So did Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Louisville, Kentucky, and suburban Northern Virginia along with the other now-booming Southern metros that were ordered to desegregate before Nixon’s guys changed the rules. Up until 1974, the trend was toward breaking down the barrier between city and suburb. Metro-wide schools early on proved dramatically successful in integrating poor and rich, black and white, urban and suburban kids, and the outcomes since then consistently prove that that success is academic as well as social. Test scores for kids of all income backgrounds and colors are much higher than in the isolated, city-only districts that are the norm throughout the Rust Belt; and in these metropolitan-wide districts, there is so high a level of civic engagement and popular support for maintaining the system that race- and class-based appeals for a return to segregation get voted down.

Gerald Grant’s short book tells this story very well. It is that rarity among policy tomes: a page-turner. The author interweaves his own experiences as a parent, teacher, and researcher into a coherent narrative of the forces that alternately evil and dim-witted politicians loosed upon the North. Urban renewal was just stupid, if well-intended; enterprise zones are well-intended but ineffectual; limited-access highways, meant to make our cities efficient, instead have proved destructive and surpassingly ugly as they cut through old neighborhoods, screwing things up in Syracuse, Buffalo, Rochester, and even in the late Jane Jacobs’s adopted Toronto. But the political calculation that Richard Nixon made in 1971, when he nominated William Rehnquist to the Supreme Court, was something beyond inadvertent or dim-witted. Borne of Nixon’s desire to keep his Southern and suburban white voters out of the hands of George Wallace and his populist racial appeal, Nixon saddled America with a Supreme Court whose decisions in the 1970s, specifically on school desegregation, proved evil.

Metro-wide school desegregation actually had popular support before the 1972 election—and legal support, too. But after Nixon’s guys changed course, Gerald Grant’s hometown of Syracuse started becoming, as Joel Giambra said so often of Buffalo, a “warehouse for poor people.”

Meanwhile, the Raleigh metro area broke down the walls between city and suburb by unifying its city and suburban schools. Raleigh and the other Southern towns had a distinct governance advantage that the fractured, “little box” metros of the North did not and do not to this day: In the South, there are city districts and county districts, but not the little micro-districts that track closely to town boundaries. Unifying Raleigh with Wake County took a decision between two districts. In Erie County, there are 29 school districts.

If you’re a suburban real-estate developer in the Rust Belt, you’ve made a lot of money from racism, and you and few of your banker friends are happy with the status quo. But there’s a lot more money for a lot more people in metropolitan regions where the schools integrate rich, middle-class, and poor. Grant points out over and over again that the true achievement of Raleigh and of the other metro-school metros is much more about integrating the social classes than it is about race.

That would be true in the Rust Belt, too, if metro schools became the norm. After all, the combined black and Hispanic populations of Erie County are only about 15 percent of the total. The County’s school-aged population is about 20 percent minority. How hard could it be to get 20 percent mixed in peacefully with the other 80 percent?

Concentrated poverty is the central problem that isolated, self-isolating Northern cities face. In Erie County, in the decades since the disastrous 5-4 Supreme Court decision rendered by Nixon’s appointees in the 1974 Detroit school desegregation case, middle-class flight from Buffalo has been continuous. Ditto Monroe County, where Rochester earned the dubious distinction in a 2007 Brookings Institution study of having the worst concentrated poverty of any city in America. Ditto Cuyahoga County and Cleveland, Wayne County and Detroit, Onondaga County and Syracuse, and on and on.

Grant cites Nixon’s recently released Oval Office tapes, in which the president of the United States instructed the attorney general and his chief of staff to get him a Supreme Court nominee who meets a specific ideological test: The nominee “…must be against busing and against forced housing integration.” Rehnquist was his man.

The political focus has ever been on race. But the 1966 report by James Coleman, which Grant cites again and again, found that class—in other words, household income—was the key factor in outcomes. “Simply put,” writes Grant, “Coleman found that the achievement of both poor and rich children was depressed by attending a school where most children came from low-income families.” We have known since 1966 that poor children do better when they attend schools in which middle- and higher-income kids predominate—and that the better-off kids do not suffer.

The ongoing peace of the Raleigh metro system was challenged over the past couple of years by some parents who objected to their kids being bused across town so that the Raleigh system could keep to its rule—that no school could have more than 40 percent poor kids. In a referendum, the drive to re-segregate by income lost. Folks there apparently figured out that things work better when there’s genuine diversity. As Grant writes:

The norms of behavior, the language spoken, and the expectations of teachers [are] vastly different [in the economically diverse school]. Gangs will not run the schools. The learning curve will be higher. Students and teachers will no longer have to confront a culture that ridicules traditional school achievement. Sloppy and vulgar speech are [sic] less likely to be tolerated. The vocabularies of poor children will grow as they interact with advantaged classmates. More will learn to read sooner. Teachers will not be overburdened and burned out, as they often are in high-poverty schools. Children will not have an easy time ducking homework assignments…more poor children will reach grade level, and they will graduate in far greater numbers.

Regionalism isn’t about saving nickels. It’s about knocking down the evil barriers, erected by a disgraced politician, that have impoverished our freshwater cities and their metro regions. Metro schools are the Rust Belt’s unfinished business. The next step in the discussion of metropolitan governance is to go back to the first step, and get serious about ending the inefficient, expensive, and suicidal isolation of the poor. Way back in the 1980s, the black sociologist William Julius Wilson told us that we don’t have to talk about race so much any more. Gerald Grant’s book shows us that the real lesson of Raleigh, Chattanooga, Charlotte, and the other metro school districts is that we should be talking about giving poor kids a chance, whatever their color, and that metro schools are the way to get the job done. Raleigh is not paradise, but it is self-sustaining, and growing, and its children have a better chance than ours do. If we want to keep our kids, we need to be brave enough, and smart enough, to keep them together.

Bruce Fisher is visiting professor of economics and finance at Buffalo State College, where he directs the Center for Economic and Policy Studies.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n1 (week of Thursday, January 7) > The Rust Belt's Unfinished Business This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue