Next story: Seven Days: The Straight Dope From the Week That Was

Spring & Shrinkage

by Bruce Fisher

The season of renewal and foolish promises

Spring is coming, so life is good. The spring uptick in local real estate sales suggests that economic recovery is budding up almost as vigorously as the daffodil and tulip bulbs we planted last autumn. In some Buffalo neighborhoods, especially those where houses cost less than $200,000, there’s hot action. Fixer-upper West Side houses are selling to urban pioneers in the area around the nationally televised Massachusetts Avenue project, though there’s a growing glut of inventory in the first-ring suburbs that is keeping prices there down. Aging boomers who are now empty-nesters are trickling into downtown condos and lofts. Grant Street businesses are edging into long-vacant storefronts. Weekday crowds at the Broadway Market (albeit Easter week) have been healthy.

Recovery? Maybe. Just don’t expect these positive developments to change the Census numbers. Buffalo, the Buffalo-Niagara metro area, and Upstate New York in general will continue to lose population for the next decade, or perhaps the next two decades—which may explain why Albany will continue to focus on Downstate rather than on where we live.

Here are the numbers:

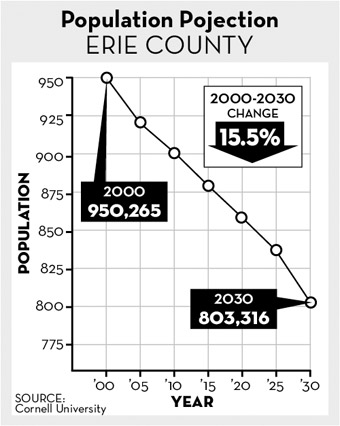

Erie County had about 950,000 residents in 2000. The just-published Census estimates that Erie County’s population dropped to 909,000 in 2009. (Rochester’s Monroe County dropped from 739,000 to 734, 000.) The Buffalo-Niagara metro area went from 1.17 million to 1.12 million, dropping by 46,000 souls. The Rochester, Syracuse, and Binghamton metros lost population, too; the only Upstate metro that gained was Albany, principally because of growth in Saratoga.

Cornell University’s demographers project that by 2020, Erie County will shrink to 850,000 and that by 2030, when the youngest Baby Boomers will be 70, Erie County will shrink to 800,000. Include Niagara County, and the metro area in 2030 will be under 1 million for the first time in 40 years. Rochester, Syracuse, and the rest of Upstate New York (except Albany) is trending the same way.

Meanwhile, there is another set of new Census estimates, with an entirely different set of projections from Cornell demographers. It’s the list of the 100 fastest-growing counties in America. Featured on that list are most of the counties of Downstate New York. Westchester County, just northward up the Hudson River from New York City, has grown from 923,000 to 956,000 since 2000. Democrat-turned-Republican Steve Levy’s Suffolk County on Long Island has grown from 1.4 million to 1.5 million in 10 years. New York City itself has grown, with Brooklyn adding 100,000 people, Manhattan up 90,000, Bronx up 60,000, and Queens up 10,000. In the next 20 years, as Upstate shrinks, the New York metro area is expected to grow tremendously, by as many as two million people.

In other words, unless something dramatic happens to change trends, our community will shrink relative to the rest of New York State.

Projects and renewal

What’s the “something dramatic” that could happen here? Could it be a change in our entrepreneurial culture? A new report by the Citizens Budget Commission in New York City mines a bunch of sources to show that, strangely, New York State doesn’t benefit much from all that venture capital that comes from Wall Street. Pennsylvania and Ohio do a heck of a lot more in investing private and public money in startups, especially the high-growth, high-paying startups that attract and keep the best and brightest university grads.

Will the transformative dramatic input be our arts and culture scene? More on that in a moment. For our size, this community does a whole lot already.

Surprisingly, in this season of renewal, our most widely-promoted and financially articulate community representatives find themselves pitching our strapped New York State government for their favorite publicly funded projects. Here’s a short list:

• Canal Side. The website for the Erie Canal Harbor project asserts that the more than $300 million in public and private money will result in Buffalo’s next “great place.” Local developer Mark Goldman has questioned how this shrinking community can afford to retain its existing commercial strips and also support a new place for the planned “restaurants, entertainment venues, retail outlets, cultural attractions, [and] public spaces.” Thanks to the New York State Power authority relicensing agreement, most of the public money for this project is in place already.

• The Medical Corridor. This segment of UB 2020, the long-term expansion plan for SUNY Buffalo, depends principally on New York State’s ability (and willingness) to increase its capital budget commitment. As I write, we await the outcome of state budget deliberations over how to close a $9 billion operating deficit; current funds at risk include operating assistance to Roswell Park Cancer Institute and to SUNY itself, which has sustained large reductions in recent years.

• The Peace Bridge. What could be a more than $500 million project all told, combining a $300 million plaza expansion and a “companion span” to the current international bridge, depends on concurrence by the Buffalo Common Council, but also on the willingness of the state and federal governments to commit so much money to a single-mode project that leaves rail and waterborne freight issues unaddressed.

Whatever the merits of these projects, they are unlikely to result in the replacement of the tens of thousands of jobs that have been lost in the region since the recession began—not this recession, but the one before this one. The labor force in the Buffalo-Niagara metro was 580,000 about 10 years ago. Today, it is 525,000.

The arts, our souls, and our economy

Labor force experts expect that, as our region’s population ages, there will be many jobs opening up—jobs currently held by Baby Boomers. There will also be some jobs, new ones, if not very high-paying, for those who want to tend to Boomers.

Back when the Boomers were young, in the 1960s and early 1970s, there was another prospect on the horizon. That was when the University at Buffalo was a leading participant in the cultural agitation everywhere present in America. For a while in the 1960s, UB had a controversial president named Martin Meyerson who brought controversial folks in from all over the planet. Some of them put Buffalo on the international creative map, including the musical innovators John Cage, Lejaren Hiller, Morton Feldman, and others; plus literary figures like John Barth, Leslie Fiedler, Raymond Federman, Dwight Macdonald, Michel Foucault, Rene Girard, and occasionally Allen Ginsburg; filmmakers who came to the Center for Media Study, and many more. (An Albright-Knox gallery curator, Heather Pesante, is putting together an exhibition of this era in Buffalo and its international significance.) The arts looked like a growing concern—just as the industrial strength of the region was beginning its eclipse.

The strong institutional base in the arts here remains a significant economic force. In the $48 billion regional economy, at least $100 million of cultural activity (salaries, sales, goods, and services) is directly traceable to the arts. That $100 million is a real number, but the 1960s and 1970s pre-eminence of Buffalo as an international center for the avant garde proved not to be either as enduring or as powerful an economic force as deindustrialization, capital flight, and population leakage. One might say that, in terms of their enduring economic impact, all those brilliant, internationally known artists and thinkers were like a long-running show that ended.

But spring is here. It’s the native creative people, not the temporary imports, who tend to liven up the place, even when the cuts in public support that could make them more economically meaningful undermine their impact.

The Census numbers are an indication that we need not just good public policy but ongoing public inputs. The good news is that there are smart people working on good public policy, like the ones making plans for green ways to fix old wastewater problems in the Buffalo-Cheektowaga-West Seneca area. Somehow something smart happened recently in City Hall, and as a result, there’s new equipment for the Olmsted Conservancy. There’s a new president coming to Buffalo State College, and the existing president at UB still wants economic development inside Buffalo, even though it’s not looking good for all those millions for the new buildings he wants. And this is the year when the Buffalo River toxic-sediment remediation will begin, potentially giving the banks of the Buffalo River a new relevance as developable property.

The question we’re going to have to start answering, as we shrink in size compared to the part of New York State that pays our bills, is how we’re going to use their money to make us less poor and needy. The smart bet is that, with money in short supply, the new Census numbers will start steering policy decisions. The days of big projects that don’t keep people may be ending.

Bruce Fisher is visiting professor of economics and finance at Buffalo State College, where he directs the Center for Economic and Policy Studies.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n13 (week of Thursday, April 1) > Spring & Shrinkage This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue