The Obsolete Man

by Bruce Fisher

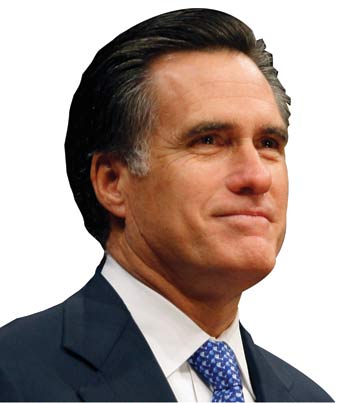

In the age of Tea and Paladino, can Mitt Romney survive?

Judging by his new book—No Apology: The Case for American Greatness (St. Martin’s Press)—the Republican Party would be fortunate indeed to have Mitt Romney as its presidential nominee in 2012. But in the age of tantrum populism, a guy who created a one-state version of the national healthcare plan just signed by Obama may have penned the last centrist statement ever intended as a GOP manifesto. The taint of concord with the reviled Other may itself have made Mitt Romney obsolete.

In 2010, there is something like a replay of late 1970s California going on, with a touch of early 1990s Waco and Oklahoma City in the air. It was in California in 1977 and 1978 that the late Howard Jarvis spearheaded the rebellion against high property taxes that culminated in the enactment, by referendum, of Proposition 13, which limited property taxes for folks who already owned houses, and effectively shifted the burden to newcomers. Robert Kuttner’s book Revolt of the Haves is about that movement, the success of which helped spur Ronald Reagan’s national anti-tax campaign in 1980.

In today’s New York State, the candidacies of Carl Paladino and Suffolk County Executive Steve Levy are Jarvis redux. Both will focus squarely on suburbanites’ burning resentment of property taxes. Homeowners in Long Island, Hudson Valley, and the Upstate metros have already shown their colors by electing and re-electing Republican county executives in Nassau, Westchester, Oneida, Onondaga, Monroe, and Erie Counties, all of whom say pretty much the same thing: We will protect homeowners from expensive welfare costs. (Paradoxically, Obama’s “stimulus” money went to counties, which typically form the smallest piece of the local property tax burden; thanks to the method of paying for Medicaid in New York State, Republican politicians who dominate their media markets look like sound fiscal managers when in fact it was Obama who bailed them out.) In the poorer, woodsier counties, and among economically marginalized whites, the old-time anti-intellectualism, racism, anti-Semitism, and ever-present resentment against complexity are all going to be electorally available to Paladino, Levy, and the relatively mild GOP front-runner Rick Lazio, too—that is, unless some Tea Party type crosses the line and emulates Timothy McVeigh, or unless an Upstate version of the Michigan Huttaree militia does something more egregious than throw a brick through Congresswoman Louise Slaughter’s window.

But none of them, not Levy, Paladino, nor Lazio, has to have a foreign policy. Candidates for state and local office sure as heck don’t have to demonstrate any understanding of national economic issues. Presidential candidates, by contrast, are supposed to be able to say something about war, trade, the Federal Reserve, oil, climate change, outer space, and the national mission.

Romney does. He calls his book No Apologies because he insists there’s something wrong with Obama’s collaborative demeanor in foreign policy. And just to make sure he’s in tune with the zeitgeist, Romney does his bit to show how much of a tantrum politician he is, too.

“I reject the view that America must decline,” writes Romney. “I believe in American exceptionalism.” The threats we face—China, Russia, jihad, and the nasty little states Iran and North Korea—need American resoluteness, Romney says, not Obama’s “American Apology Tour.”

The Romney book affords a peak into mainstream pro-business Republican Party thinking, if that still exists. One expects and one gets the usual stuff about how business does it better than government. One waits not very long to get the anti-Obama stuff about how he did the bank bailout wrong and the stimulus all wrong—and it is page-flipping, not page-turning, that even a disciplined reader does (and quickly) at the reiteration that “targeted tax cuts” would do better than direct spending to get job growth and consumer spending going again.

But the fascinating part about Romney is that he is not an angry man. He is unapologetically analytical, even intellectual. Before Romney was governor of Massachusetts and a silent co-architect of the Obama universal health-insurance coverage plan (they both consulted Jonathan Gruber, an MIT economist), Romney was a management consultant. Not burdened with excessive insight, No Apologies presents him as candidate for Management Consultant-In-Chief. Electing Mitt Romney would be like having Bain & Company, or McKinsey & Company, in charge of public policy.

Would that be so bad? Aren’t the MBAs, PhDs, lawyers, and accountants who populate these firms the best and the brightest? Sure they are. And these are also the people who realized the prophecy of that old devil communist, Vladimir Lenin, when he warned back in the 1920s that international monopoly capital would come to rule the world. These are the international firms of smart, Ivy-educated quantifiers who have enabled the triumph of financial interests over everybody else’s. Want to know how much you’ll save your shareholders by busting your union and shipping your manufacturing to China? Hire Bain, Mitt Romney’s old firm. Want to hammer the docs and nurses who spend too much and take too long doing hip replacements at your hospital? Hire McKinsey. Hire KPMG. Their service to international financial interests has been like the service of elite economists: They have helped lead policy-makers to equate the American public interest with that of investors.

It’s touching to read of Romney’s devotion to America, and only a few pages later, to read his careful warnings about how China is going to devour and dominate the whole damned world, and we’d better get our butts in gear by being smarter and working harder and studying more math and end this waste of time called bilingual education. I agree with him. Trouble is, he and his ilk, the financial and management-consultant aristos, helped empower the Chinese who have more workers who will work for less and make all of America into Buffalo.

It’s also touching to read of Romney’s devotion to the rigor and the quality of his old Michigan private school, Cranbrook, which is a Midwest version of Exeter, Choate, or Deerfield (except, like Nichols, it takes day-students). Prep schools are indeed fabulous. Energetic kids can truly thrive there. All it takes is parents who can get their hands on that wily wascally extra $50,000 of pre-tax income it takes to send a kid to Cranbrook. Yet because Romney’s pop worked for rather than inherited his kids’ tuition dough, the elder Romney inculcated a truly aristocratic (rather than money-centric) virtue in them: an appreciation of vigor, and of rigor.

Hard-working young Mitt is rigorous. He is smart, lean, handsome, and actually interested in the data he cites. And he is a GOP politician, which means that he cannot do better than chant the same old destructive mantras of free-market fundamentalism, as he does when talking about the virtues of privatizing public services. I read that as an announcement to Republican donors: When I am president, Romney says, I will open up the federal checkbook to you guys. The public will still pay for services; it’s just that the unionized Civil Service workforce will get replaced by people who work for less so that all you contractors can skim.

That’s political eloquence. Romney’s silences are eloquent, too. There is a full and lucid chapter on his evidence-based pursuit of universal health-insurance coverage in Massachusetts. There is frequent reference to lessons learned in the weed-prone Romney family garden. But there’s nary a mention of Bernard Madoff, and precious little about the financial shenanigans of Romney’s peer group on Wall Street. “We will recover from this financial crisis,” he asserts. “We always do.” Right. But there will be higher structural unemployment, because he and his fellow aristos helped ship American jobs overseas. Pursuant to evidence-based analyses of maximum efficiency, of course.

Understanding the national interest even a little bit means understanding that dropping in on an under-performing enterprise and fixing it is not the same as managing collective interests. The most bizarre bit of this book is Romney’s citing of McKinsey studies, albeit from five or six years ago, that lay out that climate change will cost a whole lot, but that American leadership will mean nothing because the Chinese will continue to ignore us even as they pump out more and more planet-altering carbon.

Romney allows himself to get this close to agreeing with Obama—to the effect that nations have to act together to deal with the big global common threat, rather than approach the world as we did in the Cold War. But in the chapter on energy, even after agreeing with Obama and climate-change luminary James Lovelock that nuclear power has to rise and fossil fuels sink, Romney whores after ethanol, coal, oil-drilling, and other established energy interests.

That’s politics. So is the unfocused, splatter-shot anger of the new Republicans, which feel like the spawn of Howard Jarvis and the militias of the Clinton years. At Paladino’s announcement rally, one of his supporters spoke harshly about how her husband’s manufacturing job was outsourced to China, and how that’s a situation that she expects her candidate for governor to fix. Levy has been actively hostile to undocumented workers on the grounds that they drive local Medicaid taxes up, and Paladino has promised to bar the “welfare” door to all but native New Yorkers. Republican politics of the Tea Party age may be about the Other more than about any issue. So if the Tea Party persists past 2010, expect it to ignore or bypass the brainy, composed, aristocratic Mitt Romney, whose book reads as if it were written for the campaign of 2008 rather than for 2012. On the chance that the anger fails or oversteps itself in 2010, though, Romney could be the white guy of 2012.

Bruce Fisher is visiting professor of economics and finance at Buffalo State College, where he directs the Center for Economic and Policy Studies.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n14 (Week of Thursday, April 8th) > The Obsolete Man This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue