Bernie Madoff's Wall Street

by Bruce Fisher

How Tea Party politics will bring the Bernies back

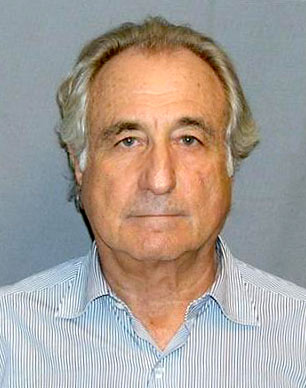

If you’re feeling blessed as the stock market rises again, go buy the book No One Would Listen by Harry Markopolos, the guy who blew the whistle on Bernard Madoff’s $50 billion Ponzi scheme. It’s about how a math nerd figured out that the magical Wall Street process of money spawning money was a fraud that some of the cleverest people in the world agreed not to disturb, mainly because too many of the clever were in on the scam—but also because underpaid, under-trained regulators were simply too stupid to catch it.

The Madoff case was the largest of its kind in history. Thousands of investors in Europe and in the US were completely wiped out. Had it not been for the housing-finance bubble, though, the genuine heroism of Harry Markopolos and a few of his friends would not have mattered. It is a scary story, and it’s extremely well told.

Here’s why it matters: Until and unless the Republican campaign strategists now at work on another Just Say No strategy change their tactics, Democrats in Congress are going to have to carry the entire burden of the financial reform legislation now being debated. And as with health insurance reform, we’ve seen how that kind of one-party process works. The good news is that there will indeed be a significant increment of change in the way health insurance companies will operate, in that they won’t be able to throw sick kids into the ditch any more, and they will have to expand their risk pools to include more healthy young people. But the bad news is that reform didn’t reform nearly enough: There is no public option; there is no cost-containment; the profiteers are still loose on the land, which is why healthcare in the USA costs 16 percent of gross domestic product while it costs 10 percent or less of other advanced countries’ output. And the Obama reform is vulnerable to an electoral mood swing between now and 2013, when it actually goes into effect.

We need much tougher stuff out of financial reform. If you read the Markopolos account closely—and it is a genuine thriller, and quite easy to get thrilled about—you’d be hard put to understand why anybody sane in Congress wouldn’t want to do not an incremental but a thorough, radical, fundamental set of financial reforms. Even faux-populist Tea Party types should be able to get behind the idea of empowering government to rein in the scam operators that the financial markets create in such distressing profusion.

For who, other than a competent government, is there to protect us from the next Bernie Madoff?

No newspapers at the SEC

My saddest memory of anti-government rhetoric is of that time in 2005 when state and local Democrats and Republicans, and the ranting ratings-chasers in the local electronic media, pestered administrators about why social workers, probation officers, child-protection workers, and other front-line public servants needed their Blackberries, their cell phones, and their cars. The Buffalo media market was treated to the spectacle of a deputy county executive vowing to chase down any nickel spent on a private ring-tone downloaded to a cell phone, even while he patiently explained that civil servants need tools.

Markopolos writes about a similar anti-government mentality, and how in Ronald Reagan’s America, it crippled the regulatory agencies that were set up during the New Deal to protect us from financial fraudsters like Madoff. Markopolos first alerted the Securities and Exchange Commission of his suspicions of Madoff back in 2000. He sent them his papers again in 2001, and enlisted the help of a securities-industry journalist that year, a guy whose paper published a pretty damning report. (Markopolos sent the SEC his stuff five times.) In 2009, after Madoff was finally clapped in irons, the dopes in charge of the much-reduced agency revealed that they didn’t have a publication budget—not even so much as a subscription to the Wall Street Journal. Only in a few of their branch offices did federal civil servants have access to a Bloomberg terminal, which is the standard-issue electronic toolbox that every financial firm in every town has. Neither did the government’s lawyers and accountants even have the kind of keyword-searching software—like any word-processing program that has been around forever—that would allow them to sift through the many complaint emails they receive, to sort the wheat of whistleblowers (“I have evidence of fraud”) from the chaff of whiners (“My stocks lost money”).

But listen as the debate about what Markopolos wants proceeds. He says that government needs to hire more elder and experienced traders and analysts and mathematicians, and that they need journals and Bloomberg terminals, and they need to go to conferences, and they need to be compensated competitively. (Bernie Madoff observed, often, that SEC personnel indeed did come to visit his office—to give him their resumes.) But we also need a “super-regulatory agency” with lots of incentives for whistleblowers.

Instead, we’re hearing the anti-government rhetoric of the Republicans and their Tea Party friends becoming more frenzied. Past all the cant of the dimwits on their bus tours, we hear Nobel Prize-winning economists from the University of Chicago, and leading Wall Street money-masters as well, still assert that markets should be allowed to self-regulate, and smirk that it is a fantasy that government will be clever enough to get regulation right.

I agree. Incompetent, resource-starved government does not work very well. So the solution is pretty straightforward: To prevent the recurrence of the greatest scam in financial history, and to prevent another sub-prime crisis and another bubble of unregulated securities, we need a competent government. That means hiring good people, giving them the right tools, and standing up to the rants of the self-interested, and of people who send tea-mail.

The good news is that the political dynamic after Democratic success on healthcare may be much more positive than before. If pro-regulation Democratic leader Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois remains steadfast, this could be the Republican sequence: First say no, then demonize the reformers, then get the Tea Party guys lathered up, then watch the Democrats rebound and pass good law, and at the end of the day the Republicans will take a beating in the post-enactment polls because middle-class America will figure out—as it did with healthcare reform—that some reform is better than no reform.

Reading about the genuine heroism of Harry Markopolos should stiffen Democratic spines, because this guy’s relentless eight-year quest is an uplifting story of persistence paying off. And it doesn’t hurt that Markopolos is ever-ready to admit his own faults, to praise other,s and to courageously name names.

But we’re still left with a cultural problem. Some people still think that money that comes from money is free. Contrast the money-world with the real world, where actual work still matters. Feeding a cow for 20 months and then slaughtering it and selling the meat is obviously hard work, not easy money: It takes labor, and money for the feed, and for the vet’s bills, and for keeping the fences up, and then one must also deal with all that excrement. Running a pizzeria costs money and takes work, as does running a law firm or a factory. But when we put money into a broker’s hands or have somebody do it for us in a pension fund, then new money that is begat by money just sort of happens. The magical process of money spawned by money has changed everything in America: The new rule of American life is that clever people don’t actually work, they just make money with money. The measure of one’s cleverness is one’s portfolio’s performance. The farther somebody is from having to shovel shit on a farm, twirl pizzas, write wills, or manage a shop floor, the smarter one is, the wiser, the more blessed.

We here in New York State play host to this world of blessings, cleverness, and scams. For the short time remaining before the offshore mobsters, the Chinese, and even our American capital-manipulators find an electronic home from which to conduct their trades, the least Congress should do is construct a better barn door. Markopolos’s insightful, learned and very moral book lays out the design for a good one.

Bruce Fisher is former deputy county executive for Erie County and visiting professor of economics and finance at Buffalo State College, where he directs the Center for Economic and Policy Studies.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n15 (The Green Issue: Week of April 15, 2010) > Bernie Madoff's Wall Street This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue