Next story: Seven Days: The Straight Dope From the Week That Was

The War For Jane Jacobs

by Bruce Fisher

Once spurned by urban planners, her legacy is now claimed by the Right and the Left and everyone in between.

Yet Buffalo still goes the way of Robert Moses.

Terry Cooke is a marathon runner, the head of the Canadian Urban Institute, and the former elected head of government in Hamilton, Ontario, that nearby industrial city where they still somehow manage to operate a big port and make steel. Hamilton was on the way to becoming Buffalo—a sprawled-out, deindustrialized former rail-head—until local leaders like Cooke and an engaged electorate transformed the place into a stabilized and now growing regional city with a merged city-county government. Last week, Cooke gave out a lifetime achievement award named for a legendary urban theorist, writer, and activist who came to fame in 1960s Manhattan when she rallied a neighborhood to prevent Washington Square Park from being turned into an expressway. The Jane Jacobs award went to Bill Davis, the former Ontario provincial leader who joined Jacobs, who had moved to Toronto in 1968, in stopping an expressway project that would have ripped Toronto in half.

Sadly for Buffalo, Jacobs bypassed Buffalo on her way from New York to Toronto: The Kensington Expressway devoured Humboldt Parkway in 1967, the year before Jacobs took up residence in a place beyond the reach of Robert Moses and his expressway-building epigones.

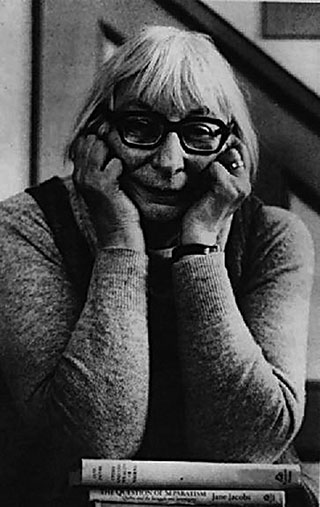

Jacobs, who died a couple of years ago, has recently become a rallying icon for urban designers and planners, professions that used to ignore her. She is the guru for a new generation of pro-city theorists and writers, and for real-estate developers, too. She’s the neighborhood activist who beat the great Robert Moses.

Moses was the planner whose name became synonymous with huge public-works projects in the 1950s and 1960s. In New York City, he is known for massive projects including the Cross Bronx Expressway and the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, but also for his defeat at the hands of Jane Jacobs. In Western New York, we know Moses not from the sorry devastation his protégés gave us in the form of the city-destroying Kensington Expressway, but from the life-giving Niagara Power Project in Lewiston, and for the parkway named after him. The power project is such a great feat of engineering and clean energy that it stands in sharp contrast to Moses’s automobile-centered work: Not only does it produce clean electricity, it also produces money, including an annual payment of about $9 million that goes into a fund in Buffalo, a fund which could change Buffalo’s future for the better, or, in the alternative, which could be squandered on an automobile-centered project.

Moses, in sum, engineered many massive concrete public works that had everything to do with cars, because Moses’s calculations always favored cars over people dwelling in their messy, idiosyncratic, slow neighborhoods. But Jacobs beat him.

So when the Canadian Urban Institute sent the Canadian leadership class a message this past week, that message took the form of an attaboy for a beloved former Ontario premiere, and the award citation was all about retelling the story of how Bill Davis and Jane Jacobs beat a Robert Moses-style expressway. “If we are building a transportation system to serve the automobile, the Spadina Expressway would be a good place to start. But if we are building a transportation system to serve people, the Spadina Expressway is a good place to stop,” is what Davis said almost 40 years ago. Go to Spadina Avenue today and you’ll see what he and Jacobs saw then: In a city almost half of whose residents were born outside Canada, Spadina is a cluttered, buzzing, crowded neighborhood whose shops’ signs are in Chinese, Vietnamese, French, Portuguese, Ukrainian, and even English. There are cars on the street, but there are also streetcars on rails, and bicycles, and pedestrians. Masses of them.

The Canadians adopted Jacobs, and now they celebrate everything urban, but not only in Toronto, where adaptive re-use of old buildings has been a given for decades. Calgary’s mayor won an Urban Institute award for a new waterfront park and residential development squarely inside his city. Hailing from medium-sized cities all across the country, a fittingly diverse assemblage of citizen groups, local government officials, not-for-profits, and students got recognized for various happy projects. For the Canadians, Jacobs is all about neighborhoods where positive, clever people live together such that they get happier in each other’s presence. But down here among us Yanks, Jacobs is becoming something of an ideological mascot-in-dispute.

Principal and influential among the new Jacobs fans are the New Urbanists, who loudly claim her. Former Milwaukee Mayor John Norquist, who heads the Congress for a New Urbanism, leads an annual “Jane Jacobs pub crawl” in Manhattan, and wherever New Urbanists meet, real-estate developers get it crammed into their heads over and over again that the next real money to be made is going to be made in cities—or in suburban places that are set up as dense, walkable replicas of city neighborhoods.

Next are the progressives who are not in the real estate business but who write admiringly of Jacobs continuously; Google her name and it’s hard not to find right-thinking liberals extolling her as a model economist of the efficiency of urban density. Greens, too, love cities; Green writers lionize Jacobs.

And now the Right wants her, too.

The relentlessly anti-government Howard Husock, of Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, might have had very wide eyes indeed last week in Toronto at seeing how non-ideological the notion of urban density has become in a country committed to the very kind of regional land-use planning that makes American conservatives choke. Husock, writing recently in the Manhattan Institute’s City Journal, claimed Jane Jacobs for the Right, and chided American liberals and leftists for misreading her signature 1961 book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, as anything other than a paean not only to free-market capitalism but also to the established American version of urbanization: Immigrant arrives in city ghetto, immigrant makes dough, immigrant books for the ’burbs making way for new immigrants.

It’s true that Jacobs described that “creative destruction” process, and the sequencing of uses of buildings in city neighborhoods. And it’s true that big bad Robert Moses was a planner, and that she hated his version of planning—which was all about cars and getting suburbanites to and from their suburbs. But in the Toronto Jacobs moved to, fought for, and stuck with, there is now a bagpiper’s tattoo for all things Jacobs that are about her adopted countrymen’s version of her, and in the actualized, implemented urbanism of Canada today, there is not a peep of dissension or protest against planning that has as its goal the urban density and agglomeration economics that Jacobs praised. Canadians claim that Jane Jacobs. But still, so do Harvard’s anti-planning Americans, including not only Husock but also the prolific young economist Edward Glaeser, who protests against things like regulations for historic preservation, claiming that they disrupt the natural, sometimes chaotic, sometimes un-pretty cycles of entrepreneurship and collapse in old neighborhoods.

Cities are complex, and she addressed that complexity, and as with any heroine who has competing fan bases, the debate will go on because she wrote so much that there’s evidence in her oeuvre for any argument you want to make. But the anti-government ideologues have a political agenda for which they mine Jane Jacobs’s work: She didn’t much like welfare spending as it was practiced in New York City in the early 1960s, and said so, and thus the “free market” boys love her for that and relentlessly bold-print those excerpts. But if you believe that welfare spending is the enemy of successful urban density, check out the European and Canadian cities that Jacobs admired: Their successful evolution to new levels of density, diversity and economic complexity has come about concurrently with much bigger social-service and income-support regimes than in America.

But let’s move on: The big issue, and the big change that hinges on which of our versions of city-loving Jane Jacobs gets emphasized, is our Robert Moses issue. That is, we have some decisions to make about oil-based personal transportation and the suburban landscapes that cheap oil and the Robert Moses mentality made possible. If, as some believe, the global crisis in petroleum will inevitably cause a massive re-migration to cities and an abandonment of suburbanization, then the progressive, green, Canadian version of Jane Jacobs will prevail. If cities are going to remain occasional entertainment venues for suburbanites who need massive subsidized parking garages so that they can drop by, dispose of some discretionary income, then burn some BP oil on their way back home via the Moses expressway, then the Manhattan Institute version of Jacobs will drive our spending. And the $9 million a year that is coming to Buffalo from the Niagara Power Project relicensing will be used to build us a Robert Moses version of urban life, rather than a Jane Jacobs version. For that’s what the proposed Bass Pro project is fundamentally about: constructing massive parking garages for car-driving visitors.

Most who claim Jacobs seem to be thinking of the spunky mom-in-tennis-shoes activist from Washington Square Park in 1963 or Spadina Avenue in 1971, when she fought big bureaucrats to defeat plans for expressways that murder neighborhoods and kill public space, especially green space.

But how are the lessons of Toronto and New York City relevant to the little cities that Jacobs leapfrogged over? And there’s another question that the great urban theorist left us: Before her death in Toronto a few years ago, Jane Jacobs began to have some misgivings about some parts of civilization—not the “civitas” part, to be sure—and she became a more nuanced thinker than the one who, earlier in her career, seemed to have a rule for everything urban based on her own Manhattan experience.

Maybe that’s because, in the 50 years since her fights with Moses, and 40 years since beating the Canadian expressway-lovers, Jacobs, and a few others, came to recognize that the suburbs are a part of city life, too.

The American city and 1968

The test case for Jane Jacobs is the city that was lost to racism, but that, paradoxically because of the biggest of big governments, became America’s most compelling example of how a new way of urban living might work—even here in the Rust Belt.

When Terry Cooke introduced the Jane Jacobs Lifetime Award, he made blunt, plain-spoken reference to what the Canadians of Bill Davis’s generation wanted to avoid. Back when they were fighting the Spadina Expressway, Cooke said, they were already well aware of how they didn’t want their city to “go the way of Buffalo, Cleveland, or Detroit, where the central city was abandoned.”

Cooke could have mentioned Washington, DC, which was similarly abandoned. But nowadays, people who love cities love much that has happened in Washington, DC. They particularly love the way some of its close-in suburbs have developed over the decades since Ronald Reagan’s “conservative” government poured billions of borrowed federal dollars into the Potomac River basin’s regional economy.

It’s either paradoxical or funny that Reagan’s anti-Washington spirit resulted in a flowering of government-stimulated wealth that is now much larger than the government spending that launched it.

The hallmark program of the Reagan years was the massive defense build-up, but his borrowed billions bought us much more. Reagan unleashed a feeding-frenzy for lobbyists which has never since abated. It brought Bentleys, minks, polished English-made shoes, and many glittering evenings to Washington, but it also brought dowdy downtown D.C. back from abandonment. Reagan’s unprecedented peacetime budget deficits, and his tax reform, plus the monument-consciousness and preservation-mindedness of the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, engendered a showy and elegant rehabilitation of Washington—much of which had been torched and abandoned in the riots that followed Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in April 1968. Harvard’s Edward Glaeser may gripe about how preservationists and their pesky rules are making Manhattan a destination for the rich alone, but Washington’s rules about keeping buildings no taller than the Capitol spire, and about preserving the “fabric” of the city by keeping the facades of old buildings intact, attracted so many prosperous people and so much redevelopment that their very presence overwhelmed the forces of decline. The strongest, largest, and most enduringly prosperous black middle class is a major achievement of the Washington metro renaissance.

Washington is hardly recognizable since the great tax-cutter came to town. The slums of O Street, the crack-infested rooming houses of Massachusetts Avenue, and the mess that was all of the central city in the mid-1980s have been succeeded by refreshed or replaced brick and stone structures that were always there but that looked like, and were, slums. A skid-row hotel that in Reagan’s re-election year hosted high-school students on field trips and delegations from impoverished western Indian tribes in $21-a-night rooms has long since been charging 10 to 15 times that rate. The retail landscape, supported by a larger and steadily growing local population, is more abundant than ever in the city’s history. Chinatown hums and is no longer marooned between an uncertain downtown and a self-contained Capitol Hill. The short walk from the Gallery Place Metro station to the new National Portrait Gallery encompasses local and chain coffee shops, restaurants, a multi-screen movie house, home-furnishings stores, clothing and jewelry and specialty shops, the offices of architects, lawyers, dentists, accountants, and consultants of every description, and there is more of the same in every direction where, in the 1980s, there was only riot wreckage and Georgetown somewhere off to the west.

Yet 40 years since King’s death and the great conflagrations, there remain great stretches of un-reclaimed territory, which is another way of saying that the urban racial and class divide lives on in even in one of the richest of America’s metros. Capitol Hill has been expensive for some time, but H Street Northeast, immediately behind the handsomely polished and happily functional Union Station, is a commercial strip that limps in the seemingly perpetual gloom of that dismal history, as does much of the rest of Northeast Washington. Only inches from the prosperity and renovation of the classic rowhouses with their tiny neat yards and Easter Egg pastel colors, the body language of this street shrugs “boundary.” It’s still a broken territory. Urban pioneers do their pioneering in places like H Street Northeast; in Washington, as in Brooklyn or even in Buffalo, that means young professionals, but first it means immigrants. There are refugees from Ethiopia’s harsh politics and wars and droughts who have escaped all that, and who are happy, and proud, to operate a coffee shop named for the owner’s home province. Men from the Ethiopian taxicab associations visit it on Sundays. Across H Street Northeast, a conspicuously Caucasian yoga studio proudly proclaims its first anniversary with a fabric sign anchored on the empty storefronts to the right and to the left.

But the plywood enclosures sealing the windows of those vacancies have been there through more than one season—they have, according to locals, been there for a generation. The upstairs offices, shopfronts and apartment buildings are largely unredeemed by tenants, and the farther from Union Station, the emptier. The growth outward from Capitol Hill is indeed occurring: There are more owner-occupied rowhouses than a decade ago, and fewer storefront churches. The sense of the street is that the four decades of abandonment, poverty, isolation, and street-crime will linger on, if not for a fifth decade, then at least a while longer.

This is, however, paradise regained compared to the great swaths of Buffalo, Detroit, Chicago, and other cities that burned in the 1968 riots—because at least in Washington, new activity is right next door. Speculation on H Street Northeast still makes sense even after the real-estate crash. It’s coming this way—you can feel it. H Street Northeast will be next to “come back.” And another 600,000 souls are projected to enter the Washington metro over the next decade.

Not so in the other burned cities of 1968. Many, many square miles of those cities are still barely, if at all, touched by the investment of capital and of hope that restores the density of dwellings and commerce, the density of plural human life that we used to call “civilization.”

Toronto: the un-hollowed city

Jane Jacobs moved from New York City to Toronto in 1968 when Toronto was a haven for young American men who liked this continent better than Vietnam’s. Toronto was then the polyglot and dense urban affair that it is today, only much smaller and much grayer. Toronto had a big university and big banks right downtown, to be sure, and it was in 1968 a growing port city that was actually benefitting from the Saint Lawrence Seaway. That’s the project that had been imagined as the great public work that would, at its completion in 1957, catapult Buffalo and other Great Lakes cities back into the first ranks of American cities. The August 15, 1955 issue of Newsweek featured a cover story on Buffalo’s rosy economic future, a future that, the magazine shouted, hinged upon the Saint Lawrence Seaway. Business moguls, planners, and politicians were all quoted to the effect that Great Lakes cities, but especially Buffalo, would thrive as never before because the new system of locks and canals would open the world to American exports, and Buffalo to a new era of prosperity.

By the mid-1970s, when Buffalo and the other Great Lakes cities saw their middle classes flee in the wake of Rehnquist’s Supreme Court decisions on school desegregation, Buffalo and the other Great Lakes cities also saw the collapse of their industrial economies—and the Saint Lawrence Seaway helped them not at all. Instead, it was Toronto that had experienced the growth, and it was Toronto that received the trade, and a lot of Vietnam War protesters, and with them, Jacobs. Toronto became Jacobs’s favorite city—full of the life, the street romance, the inexact and idiosyncratic texture that she had observed as life-creating energy in small sections of Boston, of Washington, DC, of New York City, and of the other places she had celebrated in The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

That book had made Jacobs famous. It became her platform for the decades of the 1960s through the 1990s. It is hard to imagine today, when there is a stampede to out-Jane each other, that her hypothesis was largely spurned by professional planners. For those four decades, American students and urban-oriented thinkers thought of urban life and dreamed of urban renewal, and even invented “new urbanism” to characterize some of their ersatz-urban development projects hatched far from old cities—but the planners and developers lived with the rest of Americans, in a nation whose Caucasians had abandoned cities, out in the automobile suburbs.

As Jacobs left the USA, white folks abandoned cities. The watershed year was 1968. The watershed events were those post-assassination riots. Whites abandoned cities out of fear of black violence. But whites also abandoned cities at the insistence of and with the active urging of every level of government. With subsidies and with new Kensington Expressways, federal and state and county and town governments enabled rapid suburbanization and the low-density sprawl that threw North American humanity into the thrall of automobiles, subdivision developers, and suburban politicians.

Buffalo is a prime example of the new geography of Caucasian dispersal from city to suburb. Until 1960, just over half of the one million people in the 1,000 square miles of Erie County lived within the 42 square miles of the City of Buffalo. By 2000, 70 percent of the county’s population was outside the city limits. Of the 130,000 African-Americans in Erie County in 2000, all but 10,000 lived inside city limits. Of the 800,000 whites in Erie County, more than 600,000 lived outside the city limits. Back in 1950, when the City of Buffalo was almost 600,000 strong, more than 90 percent of the people living inside the 40.5 square miles were white. In short, the white population fled while the black population stayed. The tax base moved a few miles north, a few miles south, a few miles east of the municipal and school-district boundary, and the suburban jurisdictions added population, but the population of the region stagnated. This happened in Buffalo, in Rochester, in Syracuse, in Pittsburgh, in Cleveland, in Cincinnati, and in dozens of other metros in the Great Lakes states. It’s the same story.

It is not the story, however, of Toronto.

Toronto had a different experience of 1968. Toronto in 1968 was amused by all the new American boys showing up. It was brightened by the first few coffeehouses and youth-oriented saloons and shops in the rowhouse streets just north across Bloor Street from the University. But Toronto never had crowds of angry African-Canadians torching their substandard housing and looting their neighborhoods’ commercial areas in protest over yet another murder of a beloved leader. Toronto was peaceful, staid, “diverse” in the sense we mean that term now, with calm saloons for men closed on Sundays as all the shops did, and with restaurants that were required to maintain separate entrances, away from the bar, for women.

Then Toronto suddenly changed. In 1970, political crisis in Montreal, which had been the financial and cultural capitol of Canada, hit hard. Prime Minister Trudeau declared martial law after Quebec separatists kidnapped and killed a government minister. Capital fled. That is to say, big English-speaking commercial banks and insurance companies and industrial concerns abruptly began expanding their operations in English-speaking Toronto. Within a few years, some of the power and the money of Montreal, if not the city’s cultural sophistication, shifted to Toronto. The political and cultural self-awareness and assertiveness of French-speaking Quebec was a bonanza for the gray city of Upper Canada. By every measure of population (size of workforce, per-capita income, educational attainment, number of enterprises created), of infrastructure (housing units constructed, lane-miles of road, miles of public transit, water, sewer and utility systems constructed) and of activity (tons of freight handled, number of enterprises incorporated, taxes collected), Toronto’s growth after 1970 was positive and sustained. And because of the focus by Toronto and Ontario government planners—a focus on keeping the infrastructure compact and city-focused rather than allowing the sprawl that characterizes American urban regions—the city grew in density and still grows in density. Adaptive re-use characterizes every old brewery, storehouse, distillery, and factory not still (or again) utilized for its original purpose.

It all made Jane Jacobs happy.

Yet in her last book, Dark Age Ahead, Jane Jacobs complained. She restated her ancient gripe about traffic engineers, whose antipathy to the scientific method she’d decried back in the fights over traffic-calming in Manhattan in the early 1960s. Traffic engineers had made messes in Toronto, too. In all her years in Toronto, even after the great victory over the Spadina Expressway, she nurtured a specific hatred of the lakeshore’s Gardiner Expressway.

But in her last book, she also shared her happiness about the new phenomenon of “import replacing”—the not-so-novel fact that local urban density in Toronto has created a market robust enough to support local manufacturing of furniture and other items that used to be imported. Jacobs hailed the fact that local money circulates better locally, because products that for so very long had been imported from overseas cheap-labor producers are now, in dense Toronto, being produced and sold locally.

The happy urbanist Jacobs warns, in her last book, of a “dark age” precisely like the cliché of post-Roman Europe of barbarians and illiteracy and chaos that we learned about in high school. The bad times coming are not coming due to some shortfall in Toronto’s urban success. The darkness descending on us, she says, is descending due to true science being abandoned, and self-policing by the learned professions ending, and families being so stressed that they erode, and cultural memory being obliterated, and taxes disconnecting from local needs.

This is not the book for which we should remember Jane Jacobs. Her gripe about the decline of science and of standards among professions, and her contradictory gripe about municipal-government change in the Province of Ontario, are gripes writ larger than gripes should ever get writ. (She liked local government, and wanted Toronto to be governed as a city-state, then got mad at the government she’d advocated for.) She got angry with some engineers, planners, bank economists, and other educated elites and then wrote this book, in part, to warn that it was their blindness that was dooming civilization. Some of those very local, very fleeting controversies should have been edited out of her tome.

It is when she speaks of cultural loss, though, that a chill of universal recognition descends. We have read elsewhere, especially in Jared Diamond’s Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, about societies that forget. Jacobs warns that we are forgetting about what it means to live in cities.

That’s the warning we need to heed. Driving through the sprawl of Generica—the suburban landscape that is precisely the same in suburban Buffalo as it is outside Chicago, outside Washington, outside every city—one sees what Jacobs loathed and what some (but not enough) young people now flee: the automobile-based roadside culture that depends upon endless supplies of imported energy, and that some well-meaning people now want to import into urban centers.

What the Canadians have figured out is that their taxes stay low when their cities sustain density. Spadina Avenue is all about locally owned enterprises. The density that works there and in the great cities comes about when new immigrants come in and create sustainable economies by lots of small-scale enterprises, and that happens most effectively when public infrastructure moving people around in vehicles other than cars.

If the small- and medium-sized cities are part of the same civilization that the great cities lead, then Jacobs is indeed the right guide for us all. What Jacobs contributed to our cultural discourse, a contribution that will long outlast her, is a warning that civilization is about cities—places where people live in close proximity, where they have a sense of shared identity, where they interact (shop, play, study, work, date) near where they live, and it ain’t about municipal boundaries. This is the point that her last book idiosyncratically makes. As she passed, she took a parting shot at all the Robert Moseses she could think of, re-fighting old fights. I doubt that a new urbanist, or an old urbanist, or even an ideologue could mine any one of Jacobs’s texts to find support for the idea of building parking garages for suburban day-trippers. Yet if that’s what keeps happening to public money in America, civilization will stay north of us. We will not only forget who we are: We will forget that we ever knew.

Bruce Fisher is visiting professor of economics and finance at Buffalo State College, where he directs the Center for Economic and Policy Studies.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n25 (week of Thursday, June 24) > The War For Jane Jacobs This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue