Next story: Flash Fiction: The Spider and Salt Hearts: A Fragment

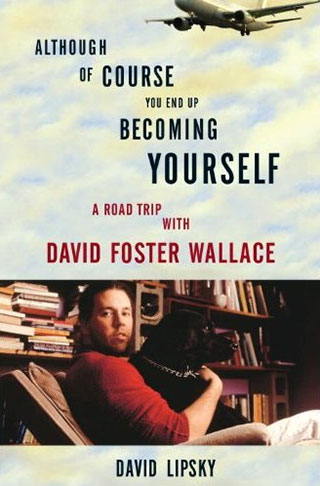

Book Review: Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself

by Aaron Jentzen

A road trip through the 1990s and the humorous, brilliant mind of writer David Foster Wallace

Imagine yourself back in 1996. You probably wouldn’t be reading this on a glowing screen, nor regularly interrupted by a small computer in your pocket. Now, try to remember March 6 through 9. Most likely, those memories are gone, devoured by the Langoliers, along with the rest of that decade.

Novelist and journalist David Lipsky spent those days alongside David Foster Wallace, then a brilliant young writer on a reluctant book tour for his magnum opus, Infinite Jest. Now, their hours of recorded conversation—interviews conducted in cars, planes, hotel rooms and Wallace’s home—are rendered vividly and mostly verbatim in Lipsky’s new book, Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip With David Foster Wallace (Broadway Books).

Rediscovering the transcripts more than a decade later, “it was just strange to make contact with the younger versions of me and this writer that I love,” says Lipsky, via phone from New York City. “It was just like being back in the car with him again.

“That’s such a weird thing about time: Everything gets lost, except for the stuff that accidentally gets recorded.” While talking about the book, Lipsky seems to unconsciously introduce other 1990s ephemera—a scene from Seinfeld, or the 1995 TV miniseries based on Stephen King’s The Langoliers, about monsters who consume the recent past.

Lipsky’s reporting, intended for Rolling Stone (where he’s now a contributing editor), never saw the light of day. Then, in 2008, Wallace took his own life, following failed treatments for depression, which he had controlled for years with medication. He was 46.

“I see that wholly as a medical thing,” says Lipsky. “It’s a tragic thing—he just got really bad medical advice.”

One consequence of his suicide is the recasting of Wallace as chronically moody, grappling with addictions, always headed toward that unhappy end. Lipsky hopes to remind readers “that what people loved about his work from the beginning was that he was so alert and alive and funny.”

Aside from some introductory material—partly drawn from a moving essay Lipsky published upon Wallace’s death—the book is simply Wallace’s humorous, insightful words, unobtrusively supported by Lipsky’s prompts and terse annotations.

Lipsky’s idea was “to let him talk, to let the story come from him, and to get out of his way as much as I could,” he says. It’s also a respectful way around Wallace’s oft-expressed concern that his words might be shaped into whatever Lipsky wanted, regardless of Wallace’s own intent or wishes.

Besides Wallace’s life story, the two discuss the writing life, the literary establishment of the day and, of course, Infinite Jest. Implicit if unspoken are questions about the nature of reporting—and about which David can rightly be considered the author. Also woven through the conversation are addictions, particularly to television and alcohol, and Wallace’s eerily prescient predictions about life in the information age.

Today, “because the computer is linked in to a web of things, you channel-surf through your life,” Lipsky observes. “[Wallace’s] guess as to how people were starting to live in the 1990s is absolutely borne out, not only with how people experience entertainment, but how we experience the texture of our lives.

“It’s this weird, discontinuous blur. And his seeing that in movies and MTV and guessing that’s where the culture would go, I thought was pretty staggering.”

In the end, Becoming Yourself is “a chance for readers to spend time with this incredible mind,” says Lipsky. “And so many things he said and felt and talked about were things I’d experienced but couldn’t phrase properly to myself. It made me feel incredibly less lonely. And so I hope it would have that effect on other people, too.”

—aaron jentzen

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n27 (week of Thursday, July 8) > Literary Buffalo > Book Review: Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue