Next story: Ralph Nader Rolls Into Buffalo August 3rd

Fishing For Salvation

by Bruce Fisher

Subsidies and Handouts Versus Clean and Green

When a group of concerned citizens joined with a veteran attorney to file a lawsuit against Bass Pro Outdoor World LLC, and all the government entities that want this private Missouri company to get public New York money, a 20-year-old community conversation about Buffalo’s identity came of age.

Many people are perplexed that yet another lawsuit has been filed concerning the Canal District. That’s the area in and around the 12-acre parcel of City-owned land that now has a re-watered portion of the Commercial Slip in which boats can actually dock, just as they did for 130 years before the Commercial Slip was filled in and the area paved over. Across the street from where the War Memorial Stadium was torn down last year, there’s also a replica of the old “bowstring” bridge, and a pretty good portion of the Central Wharf, too. Much of the mid-19th century historic street pattern has been restored, and there are 97 parcels, all told, in the Canal District, pretty much ready to be developed if anybody wants to do so.

Preservationists are generally happy with the victory they achieved: the Slip, the Wharf, the streets and the bridge were the four critical elements they’d sought, and now, right there where they used to be, right there in Buffalo’s historic Canal District, they exist out in the open, where before they were buried. The Naval and Serviceman’s Park next door has a new building that is architecturally compatible with the Canal District structures that had been there in Buffalo Harbor’s century-long heyday. The foundation stones of Dug’s Dive, the notorious saloon that doubled as a hiding place for enslaved people headed north for freedom in Canada, are there, and marked, and doing fine with the exposure. The limestone canal stones are there, too, just as they are along the length of the Black Rock canal, to the everlasting embarrassment of a UB professor who warned that exposing the original Canal District stones might cause them to “explode.” None have.

Citizen activism, activist journalism, lawsuits and some sensitive leadership by elected officials achieved all that. The Canal District began looking like a winner by 2007 when the elements people had fought for started becoming visible. This summer, despite parking not being immediately adjacent to the site, there is a steady trickle of visitors on warm weekdays, a bit more than a trickle on weekends, and good crowds when concerts are held there. It works as a seasonal attraction, and as a year-round place for some of the nearly 40,000 downtown workers to stroll through at lunchtime, even when the winter winds off Lake Ere are very tough to face.

But then came Bass Pro, and Canal Side, and what many had seen as a victory for Buffalo’s genuine heritage was re-imagined by a new group of empowered but not elected officials, namely, the Board of Directors of the Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation, as an opportunity for subsidized retail development.

The fight that has been joined today is a long time coming, but it was inevitable, because some very different views of Buffalo’s future are in conflict—as is the question of how more than $150 million in public funds should be spent.

The lawsuit

The business owners argue that this metro area has a far greater supply of retail stores, restaurants, hotels and office buildings than there is demand for them. The economists say that the economic impact of subsidized development will merely be to displace existing firms. The policy people say that more and better jobs will come about if the waterfront project refocuses on clean water and green space, the original purpose of the public funds at issue. The preservationists would love to see enterprises in the Canal District—fashioned enterprises, the ones that pay their own way.

Mark Goldman, the entrepreneur who is justly credited with resurrecting Chippewa Street as an entertainment district, the historian who has published three books about Buffalo, the preservationist who has put his own money up for his developments, is the lead plaintiff in the lawsuit.

Goldman is joined by Scot Fisher, the president of Righteous Babe Records, business partner with Ani DiFranco in saving and restoring the former Asbury Methodist Church, and the preservation enthusiast who led a petition campaign that gathered nearly 15,000 signatures from citizens inside and outside of Buffalo in favor of restoring the Commercial Slip.

Susan Davis, associate professor of Economics at Buffalo State College, joined the suit with a statement that is simple and direct: “Public money is legitimately used to build the infrastructure for commerce, but not to give one business an advantage over others. The Bass Pro deal is crony capitalism at its crudest and should not be tolerated.”

UB Political Science professor and attorney Stephen Halpern and Elizabeth P. Stanton, a professor of occupational therapy at D’Youville College, are also parties.

So am I. The attorney for the case is Arthur J. Giacalone, Esq.

The lawsuit says that it’s a violation of the New York State Constitution to make a gift or loan of public funds to any private enterprise. The more than $150 million of public funds from various sources—over $105 million is from the New York State Power Authority—are all public money. Some would-be theologians have tried to parse “taxpayer” money from “settlement” money, but here’s the legal fact: it’s our money. Public. Period.

Ironically, it wasn’t until some Tea Party supporters won their own anti-corporate welfare case a few weeks ago that anybody in New York State had ever successfully argued against the massive subsidies handed out by Empire State Development Corporation and its subsidiaries (the Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation is one such). That’s all changed now—even here in Erie County, the home of a case from 39 years ago involving Ralph Wilson Stadium, when the idea of giving a private entity public money for a “public purpose,” like entertainment, still had to be litigated.

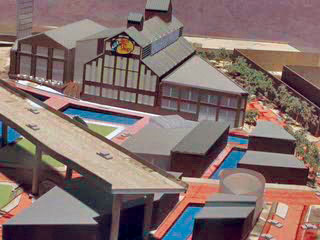

But that was a case about a stadium that arguably provided a unique public entertainment. This case is about a handout of public money to a chain retailer with a cookie-cutter approach to selling stuff that has nothing to do with Buffalo. The people in charge of the project want to put over $150 million in public money into a big retail and restaurant complex—$35 million in direct subsidy for Bass Pro’s proposed store building, plus $1 a year rent for them, plus 30 “controlled” boat slips at the end of the Central Wharf for them, plus parking for school-bus-length “recreational vehicles” for fishing-tackle customers, plus thousands of underground parking spaces and some ersatz (fake, non-navigable, 3-foot-deep) “canal” replicas.

Conflict of interest?

The lawsuit addresses a couple of procedural issues—including how it was that Empire State Development Corporation decided to rubber-stamp an Environmental Impact Statement before it was even completed. But the suit also takes on one of the more glaring examples of inside baseball to have come to light in recent years.

Here’s how Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) got the New York Power Authority (NYPA) to hand over a 30-year stream of payments worth a few million a year: ESDC had its own employee, an attorney who happens also to chair the State Economic Development Power Allocation Board, to okay the deal.

Sweet deal, says ESDC! Our guy says that we get to hand out his money to our friends.

But there’s a problem: there are rules that even the State Economic Development Power Allocation Board has to follow, specifically, its own rules, and they are pretty precise about where NYPA power and money can go.

So here is what the people who filed the suit want. First, we’d like the Court to stop money from being spent until the case is decided. If the money disappears into the project, it’s gone forever, and the good work that our Congressional Delegation and the previous County administration did in getting a settlement from NYPA will be gone. There is a good use for all that money—the use for which it was originally sought, namely, to clean up the filthy Buffalo River basin, which is full of what we flush into it every time winter runoff and spring, summer and fall rains make our sewers overflow. Greenspace on the waterfront, including the river’s banks, is a sane and worthy and achievable goal. Water that doesn’t stink? That doesn’t have to be combed for “brown trout”? Priceless.

Second, we’d like the subsidies for Bass Pro and for the mystery “second anchor tenant” to be voided as violations of the New York State Constitution’s clear prohibition of gifts or loans to private parties.

Third, we’d like the State agencies, authorities, boards, corporate governmental agencies, municipalities and their employees to follow their own rules for a change, especially concerning the $105 million in NYPA money that has been shunted into the Canal Side project.

The true deliverable

But there’s more, and this the lawsuit can’t deliver. Everybody who worked for or signed a petition in support of the Commercial Slip knows what we’re talking about: Buffalo has to stop grasping at big projects that always promise regional transformation but that deliver only short-term economic impact.

The rules of globalization do not favor us. All the public subsidies to the GM PowerTrain project in the first years of this decade were supposed to help the region retain about 5,000 jobs there. Today, there are 1,000 jobs, or fewer. HSBC Bank may or may not stay in the HSBC tower. HSBC’s North American operations center is in Vancouver, not Buffalo; its chief of Information Technology operates out of a brand-new office north of Chicago; its global CEO just moved to Hong Kong.

Meanwhile, as Great Lakes cities that used to be global leaders in manufacturing struggle, we seek to re-invent ourselves. It’s hard work, and nobody has yet figured out how to stop the population from shrinking.

Buffalo just held a weekend Garden Walk that I can hear the economic “development” geniuses all laughing about. But check this out: we hosted some senior planning officials from another shrinking Great Lakes metro, Cleveland, this past weekend. They walked and toured the part of Buffalo that lies west of Main Street, south of Delaware Park and north of downtown. They were astounded by the level of citizen engagement. They were thunderstruck that there is what one termed an “intact fabric” of older housing where reconstruction, rehabilitation and adaptive re-use projects were noticeably underway. Cleveland, a city of under 450,000 in a region of 2 million, used to be 900,000. Cleveland wants to learn from Buffalo’s citizens and community groups.

So we discussed the challenges that Great Lakes metros all share—especially the fact that our politicians and civic leaders cannot quite bring themselves to accept that our population will continue to shrink. (The Buffalo metro area will shrink by as few as 50,000 and as many as 100,000 people in the next two decades, according to independent estimates by the US Census Bureau, a project at Cornell University and one at the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School of Business.)

When the conversation about the Canal District began in the 1990s, everybody had experienced shrinkage and decline, but the age of the Big Project was in full swing. Jim Griffin was mayor, Dennis Gorski was County Executive, Mario Cuomo was governor and the public toolbox included an entity called the Horizons Waterfront Commission. Buffalo’s unique history wasn’t of much concern to anybody official. Luckily for those who like what is uniquely Buffalo about Buffalo—even an area of our town that was synonymous with violent crime, prostitution, pollution, bad smells and bad politics for a hundred years—Horizons moved at a glacial pace. By 1999 when Dennis Gorski was running for re-election, a polyglot group of activists correctly sensed that the pro-preservation challenger Joel Giambra, author of a much-derided but prescient “Canal Village” plan ten years before, wanted to save what was left of the Erie Canal’s terminus. Activism, clever demonstrations, relentless editorializing and much litigation ensued. By and by, Giambra engineered support from then-governor George Pataki, who happily stood on the deck of one of the blue-water warships that Jim Giffin had installed on the Buffalo River and ceremoniously accepted, on the 175th anniversary of Governor DeWitt Clinton’s inauguration of the Erie Canal, a red jug full of Great Lakes water, which he promised to “marry,” as his predecessor had done, with the salt water of New York harbor.

Those of us who were involved in some or even much of that history liked that outcome. This being public land, of course, and political careers being as evanescent as they are, by 2007, when Giambra was no longer popular and Pataki was no longer governor, the current crop of the politically powerful tried to undo what preservationists, elected officials, lawyers and judges had agreed upon.

The lawsuit we filed this week is an 11th-hour attempt to keep what was won, and to knock some sense into folks, too. Our region is over-retailed, and our water is dirty, and generations of Buffalo residents yet to be born will benefit more, body and soul, will and wallet, from a steady effort to reclaim public space than from a crash program in corporate welfare. The NYPA money could fund a lot of hardhats working to give us some more clean and a lot more green. If Goldman and his fellow plaintiffs prevail, we still have a chance at that kind of waterfront. If we lose, congratulations, folks: you’ve just bought yourselves some more stores, maybe a bank building, lots of parking spaces for RVs, and some fake canals. Remember, though, to hold your nose when you visit it. You’ll need to.

Bruce Fisher is visiting professor of economics and finance at Buffalo State College, where he directs the Center for Economic and Policy Studies.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n30 (Week of Thursday, July 29) > Fishing For Salvation This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue