Sex and the Single Flower

by Jack Foran

Botanical art @ the Central Library

Still feeling some post-Garden Walk withdrawal?

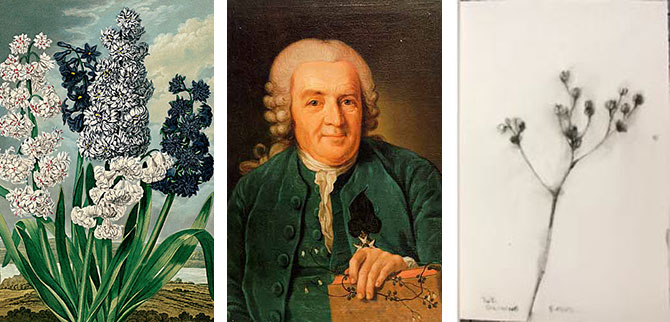

The downtown library has a terrific show of flower illustrations and related materials from its Rare Books collection. The items date from the Renaissance to the present, but particularly flower books from the 18th and 19th centuries, when the art of flower painting took off. The visual focal point is the lavish flower art from an 1807 volume by Robert John Thornton with the short title The Temple of Flora.

The intellectual focal point, however, is the breakthrough scientific contribution of Swedish botanist and father of the critical scientific sub-category of taxonomy, Carl von Linnaeus. His comparatively unimpressive volume (it is eclipsed by some of the huge flower illustration books) from 1753 is on display in a glass case.

Taxonomy means putting things in order, with connotation everything. For botany, every plant, every flower. Linnaeus classified. He distinguished. He assigned names, by genus and species.

Not very sexy, right? Actually, extremely sexy. Before Linnaeus, botanical illustrations showed the plant as if you’d just pulled it up out of the ground, roots and all, and made a drawing, then maybe a woodcut, maybe colored in.

After Linnaeus, illustrations focused on the above-ground plant and particularly the flower, the reproductive part, and often also featured, off to the side, auxiliary small drawings of the actual reproductive apparatus. Inner organs, as it were.

Before Linnaeus, plant illustrations depicted what looked like (because they were) dead specimens. Science in a bad sense. At best, we kill to dissect. After Linnaeus, the illustrations focused on the living flower. On beauty, that is, even before science.

The full title of Thornton’s volume—a product of the botanical interest in general and flower enthusiasm in particular touched off by Linnaeus’ work—is New Illustration of the Sexual System of Carolus von Linnaeus: and the Temple of Flora, or Garden of Nature.

And while Thornton’s illustrations lack the separate sexual parts depictions (an overt scientific approach would have spoiled the realistic and/or dramatic effects he strove for), the flower pictures (mezzotints, a type of colored engravings, based on initial paintings) can be positively lurid. Rather shocking in their vivid and exotic colors and patterns. You want to tell them to go get something on. Get decent.

Such realistic and/or dramatic effects as, for the American cowslip, in the distant background, a view of ships at sea under a threatening sky. Or, in the case of the Nodding Renealmia, the flowers seem to be shedding actual tears.

Other post-Linnaean illustrations are by William Curtis, who published a large work on plants growing around the city of London, and founded Curtis’s Botanical Magazine to keep the scientific and other interested community updated on the latest botanical findings, and Harriet Miner Stewart, an American, who specialized in the illustrations of orchids.

Cultivation of orchids, a tropical flower, became a rage among the 19th-century well-to-do following the invention of glass greenhouses. The ardor for orchids never reached quite the heights of the craze over tulips in Holland in the 1600s, but did garner designations such as orchidomania and orchidelerium in the Victorian era.

Before Linnaeus, the flower and plant depictions are mostly from what are called “herbals,” manuals devoted to plants supposed to have medicinal properties, and more or less focused on medicinal varieties, with instructions for preparation and use. For example, the entry for foxglove, or Digitalis, instructs boiling in water or wine, which resulting concoction, it promises, is sovereign for “the thick toughnesse of grosse and slimie phlegme and naughty humors.”

There’s a large woodcut from 1629 depicting the pre-fall Garden of Eden—Eve innocently picking flowers, Adam ominously contemplating a particular tree, though no snake in sight—but relocated to England apparently. Talk about rank Britanno-chauvinism! It was the frontispiece for a volume on wild plants native to England. (On the other hand, Shakespeare just a few years earlier had written “this scepter’d isle…this other Eden, demi-paradise…this England.”)

The exhibit also includes several items by Fredonia artist Timothy Frerichs, who teaches at SUC Fredonia and recently had a grant to work in Sweden, where he spent substantial time in the Uppsala University Botanical Garden, where Linnaeus did his work. On display from Frerichs are an ink sketch of a flower, a notebook recording what looks like some serious plant inventorying—reminiscent of Linnaeus’ life work—and a videotape of a quiet walk through the garden—it looks like about dusk, the light always fading—to a soundtrack of a soft crunch, crunch of footsteps on gravel paths.

All the materials on display are from the Rare Books collection, except the Frerichs materials, which are on loan from the artist. The exhibit was conceived and put together by the Rare Books staff, and was designed by consultant David Cinquino. The remarkable photo reproductions are by photographer Todd Treat.

The flowers exhibit is up through September 26.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n34 (week of Thursday, August 26) > Sex and the Single Flower This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue