Topsy, Can You Hear Me?

by Jack Foran

A conversation with the elephant Edison killed for money

I was skeptical when I heard artist Gary Nickard was going to perform a séance to contact the spirit of Topsy, the circus elephant Thomas Edison electrocuted to demonstrate how lethal alternating current could be (versus his own proprietary direct current, which of course would have been just as lethal, but he used alternating current for executions).

But then he did actually contact Topsy. This occurred at the Beyond/In Western New York exhibit at the Carnegie Art Center in North Tonawanda. Similar séances are scheduled—but of course with no guarantee that they will actually get in touch with Topsy—at the Carnegie facility on November 4 and November 18, both at 7pm.

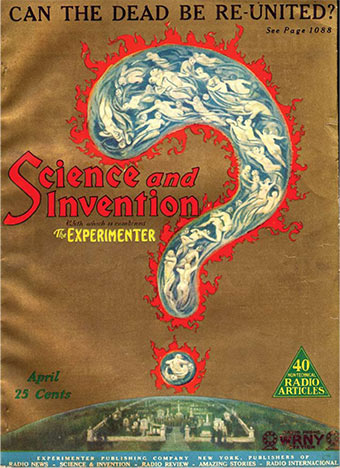

Operating a complicated array of radio equipment that included a Tesla spark-gap transmitter and Marconi-type crystal receiver, both tuned to 1485 kHz, the supposed spirit world frequency, Nickard sent messages to Topsy, via Morse code, and got back answers, albeit sometimes a little incoherent. As if maybe due to the rather primitive radio apparatus, either the questions or the answers didn’t transmit so well. (Another possibility would be that Topsy is losing it. If that can happen in the spirit world. You wouldn’t think so, but who knows?)

Some of the back and forth went as follows:

Q: “Have you ever met Edison or Tesla?”

A: “Only Edison.”

Q: “Has Edison apologized?”

A: “Farewell.”

Q: “Do you seek revenge?”

A: “No.”

Q: “Did they poison or electrocute you?”

Answer: “Want banana.”

Topsy was a famous attraction in her younger days, but then wasn’t so young or attractive anymore, and had been neglected and possibly abused for several years before an unfortunate incident when a man tossed a lit cigarette in her mouth.

Understandably, Topsy went a little berserk, and wound up killing one man and severely injuring the guy who threw the cigarette.

The verdict for Topsy was capital punishment. Which gave Edison a chance to reiterate his message about the mortal danger of AC current by rigging up a device—an electrified platform, basically—that could kill an elephant.

Some years before, Edison had convinced the New York State Legislature to use AC for its innovational execution instrument, the electric chair.

The electric chair gambit came at the height of the so-called Battle of the Currents between Edison and George Westinghouse over electrical power production at Niagara Falls, which hinged on the possibility of long-distance transmission of the electricity, from Niagara Falls to Buffalo.

The Topsy execution came in 1903. By that time, Westinghouse—and his genius assistant Nikola Tesla, who developed AC, which was economically transmissible over a distance, which DC wasn’t—had already won the Niagara Falls competition. But Edison still was at pains to establish in the public mind that AC was too dangerous for domestic use, which was where Edison’s interests, as an inventor and a businessman, were concentrated.

Edison’s principal and fixated focus regarding utilization of electricity was in domestic applications. Electricity for lighting, above all, replacing gas lighting, the previous state-of-the-art lighting method. Edison’s huge and pervasive blind spot was regarding use of electricity for industry, to power factories. He couldn’t see it. Because what need? There was the steam engine for that.

Back to Topsy. Perhaps the most remarkable thing we learned about this wonderful animal was that, in addition to all the circus tricks she must have known to make her so famous, she also knew Morse code.

—jack foran

• • •

Because blessed are the humble, Jeremy Bailey’s performance at various Beyond/In sites should not go unremembered. The locales were lavatories—men’s, but women were welcome and did not seem shy about stopping in—at several of the galleries.

To the gathered audience he would explain that he was invited to participate in the biennial exhibition, but then informed that actually, because of the large number of exhibitors and exhibits, there was really no space available for him.

Not dismayed, he inquired about what space there might be available. It turned out the only space left was in the lavatories. He took it. “You’ve got to start somewhere,” he said.

Taking the long view, he said it was a prestigious thing to exhibit at a place like the Burchfield Penney. It goes on your resume, he said, that you submit to apply for other exhibit opportunities. “And they don’t know where you performed.”

One advantage of the lavatory installation, he said, was that he got to meet most of the other artists, when they visited his space.

Other artists brought him in meals during his performances. And in the meantime he worked on a computer program he was developing, that seemed to be kind of a digital alternative to graffiti. The name of the computer program was “Maximus P.”

—jack foran

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n41 (Week of Thursday, October 14) > Topsy, Can You Hear Me? This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue