Next story: Bruce Adams' Divine Beauty at Starlight Studio and Gallery

Beyond/In Artists Who Engage in the Theme of Electricity and Alternating Currents

by Jack Foran

The Electric Company

The nominal official theme of the Beyond/In Western New York exhibit—subtitled “Alternating Currents”—related to the development of commercial hydroelectrical power here a century or so ago. Which amounted to the invention and development of alternating current electricity by supergenius Nikola Tesla.

Some of the artists even addressed this theme. The artist who did so most notably is Reinhard Reitzenstein, with his iron framework sculptural installation in a grassy field near the intersection of Smith and Exchange streets, on the edge of the Larkin District.

The piece is basically an arch. Or you could think of it—actually you’re supposed to think of it—as a collapsed electrical tower of some sort. A failed tower.

The name of the piece is almost as long as the piece itself: It Has to Have a Grip on the Earth So That the Whole of This Globe Can Quiver. That’s a quote from Tesla, describing his colossal Wardenclyffe tower project on Long Island that was supposed to provide a global system of wireless communication that would tie into existing telegraph and telephone systems. Tie into everything. Tesla was inventing radio at the time. But the Wardenclyffe project wasn’t about—or simply about—communication through the airwaves, through the atmosphere, but through the earth, actually, which Tesla wanted to treat, via the Wardenclyffe project, as a huge electrical conductor.

The Wardenclyffe tower comprised a huge electrical transformer—Tesla invented the transformer, an apparatus to raise and lower voltage and integral component of AC, the chief feature of which is that it allows manipulation of voltage—that he called a magnifying transmitter. The magnifying transmitter would boost the voltage to enormous levels and conduct it into the earth at a frequency resonant with the natural vibrational frequency of the earth, enabling transmission through the earth with relative ease.

To do this, of course, the magnetic transmitter had to be gargantuan (see Tesla quote and title of the Reitzenstein piece). The Wardenclyffe tower project ultimately failed, partly perhaps because of insufficient funding for such a big project. Though Tesla had already invented alternating current, because of the enormity of his subsequent projects and ideas, he was beginning to get a reputation as a bit of a mad scientist. (Not to mention his personal quirks. He washed his hands a lot.)

The Reitzenstein piece works as a recollection of the Wardenclyffe tower, but also as a semi-abstract sculpture that puns on arch and arc, as in a bolt of electricity. A bolt of electricity leaping across or through the earth. From ground to ground, as it were. Which may make more sense as an imaginative artistic concept than physical reality concept. (Tesla’s genius seemed to be an ability to reconcile and integrate these two categories.)

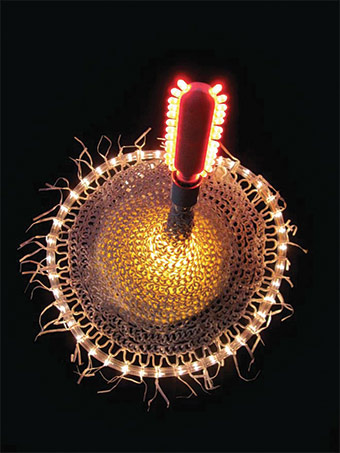

Meanwhile, Lisa Neighbour’s works at the Carnegie Art Center combine electrical components and clothing items as if to suggest the spiritual aspect, the spiritual aura, of the wearer, or former wearer, and question and explore notions of spiritualism in general.

Interest in spiritualism—in the form of efforts to communicate with the deceased—was greatly abetted by the serious development of electricity around the turn of the century. Spiritualism and electricity seemed to have some vital connection as invisible and mysterious forces, ripe to be tapped. And undeniably real, in the one case, so why not in the other?

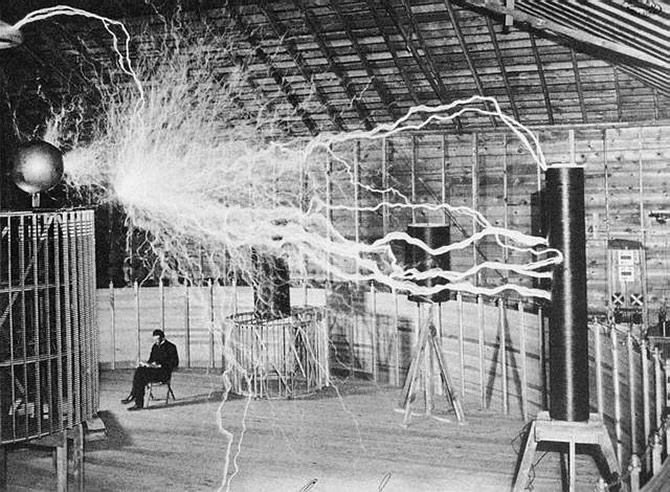

The electrified clothing connection to the turn-of-the-20th-century historical period seems less than compelling. More compelling is the remarkable visual similarity between one of Neighbour’s electrified clothing pieces and a photo of an early version of Tesla’s magnifying transmitter. The photo shows the transmitter shooting out myriad bolts of essentially lightning while Tesla himself sits placidly reading just below the main lightning storm.

The photo conveys the tremendous power of the electrical forces he was able to produce with his mechanism, and at the same time his confident understanding and control of even such tremendous forces. (Tesla’s notes reveal that the photo is actually a double exposure—a photo of the magnetic transmitter in operation, superimposed over a photo of Tesla sitting reading.)

In the adjacent room at the Carnegie Art Center, artist Gary Nickard takes on the topics of spiritualism and the development of electricity—particularly the so-called “War of the Currents” between Tesla and Thomas Edison, who held the patents on DC, and so had much to lose if AC became a commercial reality—with séances intended to contact the spirit of the circus elephant Edison electrocuted with AC to demonstrate the lethal danger of that type of electricity.

Artist Alex Young has a number of banners in various locations around the city proclaiming King Camp Gillette’s hare-brained 1890s utopian scheme to locate the entire population of the United States in Western New York, in one huge multiplex unit to be powered by Niagara Falls.

Gillette’s scheme of course was never implemented. But it is significant as one of a series of grandiose civil and social engineering projects conceived for and sometimes imposed on Western New York, focused on the falls, from John Love’s now-famous hydraulic canal to Robert Moses’ unfortunate riverside expressway system from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario.

Other works in the biennial exhibit use electricity in a way that may constitute a nod to the historical development of electricity theme. For example, Bill Sack’s quirky assemblage of nonsense mechanisms that shake and rattle (audio cassette cases) and roll (cylinder CD boxes) when remotely triggered by the proximity of a human observer. Sack’s piece is in the Hi-Temp Fabrication building on Perry Street, next to the hockey arena. Or Liz Phillips’ remotely triggered audio piece emanating Niagara River water sounds, in the entryway to the Albright-Knox.

Other, unofficial, themes for other occasions: death and decay, and the digital world.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n43 (week of Thursday, October 28) > Art Scene > Beyond/In Artists Who Engage in the Theme of Electricity and Alternating Currents This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue