Next story: Paging Dr. Bernanke

Aspirations and Inspirations

by Geoff Kelly

The latest in a series of public forums on waterfront development aims to infuse the conversation with creativity

When Mark Goldman joined a lawsuit that aimed to scuttle the proposal to subsidize a megalithic Bass Pro store in Buffalo’s Inner Harbor, he did it because he knew—as an entrepreneur, as a historian, as an ardent preservationist—that there had to be a better vision for the redevelopment of Buffalo’s waterfront than big-box retail.

Maybe it was serendipity, maybe it was cause and effect: Not long after Goldman vs. Bass Pro was filed in the courts, Bass Pro pulled the plug on its nine-year negotiation with city and state officials.

With the proposed Canal Side development suddenly unanchored, Buffalo Mayor Byron Brown tried to solicit ideas for replacements from the public. That effort yielded scattershot results and no particular direction. The Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation continued (and continues) to cast around for another big anchor tenant of some description around which to build Canal Side—so far, with no success.

In the vacuum, Goldman and his fellow plaintiffs joined with the Canal Side Community Alliance—a coalition of more than 40 community groups that have been fighting ECHDC for a community benefit agreement—to present a series of public meetings by which they hope to create a new direction for development of the Inner Harbor, based on ideas solicited from and supported by community that will use (and pay for) whatever is eventually built there.

The first of these meetings took place two weeks ago. Organized by Bruce Fisher, an AV columnist and visiting professor at Buffalo State College’s Department of Economic and Finance, the October 23 forum in the auditorium of the Burchfield Penney Art Center focused on environmental, transportation, and public financing issues. About 100 people attended.

This Saturday, November 6, at 2pm, the second forum takes place at City Honors School (186 East North Street). This one is organized and hosted by Goldman, and the emphasis is decidedly different: “Aspirations and Inspirations: Imagining the Buffalo Waterfront” is intended to introduce new ways of thinking about the waterfront.

“I want to inject an artistic sensibility to the way we think about redeveloping this vital element in or city’s landscape and history,” Goldman said recently. He was inspired by the vibrancy of the opening weekend of the Beyond/In Western New York exhibit in September, when thousands of Western New Yorkers spent all weekend chasing after and finding rich and novel cultural experiences.

“That energy was incredible, inspirational,” Goldman said. “I just think there has to be a way to bring some of that energy and creativity to the discussion about what we should do with this vital public space.”

Asking the right questions

To that end, Goldman has lined up two keynote speakers for the forum. The first is Fred Kent, the founder and the director for Project for Public Spaces, a nonprofit planning, design, and educational organization that helps guide communities toward a clear vision of the public space they want and the means to achieve it.

Kent calls what his organization does “placemaking,” and describes it as a “bottom-up” approach to planning.

“The whole idea of placemaking is really grassroots,” he says. “It’s really simple because it’s just drawing on people in a community to tell you what they’d like to do in a particular place, or at a particular street corner. It’s taking the wisdom that they have just by being where they are.”

The facilitators from Project for Public Spaces will map a potential project area and divide it into a number of discrete locations. (Kent uses the number 10, which is instrumental in the group’s thinking about cities and neighborhoods: A great city has 10 great destinations, he says by way of example; a great neighborhood has 10 destinations; a great street has 10 destinations; and each destination has 10 things to do or places to be. Think of a bookstore with seats in the window, a display of books on the sidewalk, a bulletin board, a place for readings, etc.) They then dispatch teams of people drawn from the community to visit each location within the project area and report back about the sorts of things they’d like to do there: Is this a place to have lunch? Is this a place to see a concert or to shop? Is this a place to throw a frisbee or visit an art gallery?

In other words, their job is to ask the right questions. Then listen for the answers. When all the teams have reported back, they add up their ideas and create an idea for the whole project area. “The response is also amazing,” Kent says. “You watch it unfold as they report back. It’s amazing what people intuitively know about what a space ought to be.”

Kent says the process has only failed to deliver a satisfactory result once, when partisans of a cultural institution engineered a conclusion by stacking the discussions with their own people, who shilled for the plan the institution wanted. The community at large rejected the result.

Waterfronts tend to elicit an almost Pavlovian request for parks, Kent says, but he’s found that when his team bores deeper, they find that parks are not the priority for most waterfront communities.

“There’s a natural tendency to ask for parks, or green space, but that’s not what people really want,” he says. “They want places to go and things to do. What they’re really after is a place they can together and have fun, have a meal, be around other people, be at a market, have a lot of green, maybe a playground.”

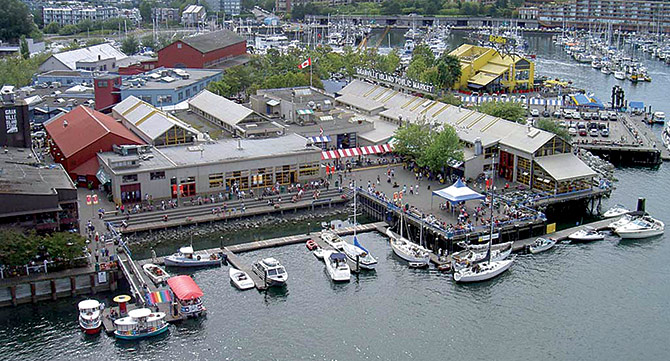

Kent says that what most people really want is a sort of 19th-century pleasure garden, where a park-like environment is home to diverse destinations—a place that draws people to a variety of small attractions as opposed to one, monolithic attraction—e.g. a big-box retailer, a sports arena, an aquarium. Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen is one famous example. Another, perhaps more informative example is Granville Island in Vancouver, which has some of the elements of a pleasure garden in a decidedly urban context.

“A lot of cities think that if they make this big iconic architecture or this big mixed-use development, that will be the key,” Kent says. “What we’re saying, what we know, is that if you look at Bilbao in Spain, they only get about 800,000 visitors a year, and they’re all tourists. You take Granville Island, you get 10 million visitors, and a substantial number of them are locals who come on a repeating basis. There are 3,000 people who work on Granville Island and 270 businesses. When you go to Bilbao, there’s a museum and the people who work in the museum. And that’s it.”

Kent calls the sort of development plan that produces a Granville Island “lighter, quicker, cheaper”: a means by which to achieve short-term results using distinctive local resources and activities and talents, whether cultural or retail, rather than engaging big outside design firms that import ideas and destinations from elsewhere.

Indeed, Granville Island is the second-biggest draw in Canada, trailing only Niagara Falls, Ontario.

“The economy of Granville island is something like $325 million a year in revenues generated,” Kent says.

“You’re looking at two entirely different approaches—one that fails to deliver its promise, and one that is tried and true but not done very often because everyone is going toward this big mixed-use development idea that brings in big-name stores. But we now know very few people are interested in going to the same store in every city in the world.”

The development of Buffalo’s Inner harbor has been shackled to a handful of core principles for at least 25 years, since the creation of the Horizons Waterfront Commission: a giant, subsidized anchor attraction of some kind, some greenspace along the water, a single, retail-oriented developer for the Inner Harbor and some of the surrounding blocks.

The key to overcoming an entrenched idea of how a space ought to be developed, Kent says, is to show government officials the benefits of delivering on a community-generated vision.

“If I let the people come up with a vision and then my job is to help them implement it, that’s great role for a politician because you can’t lose,” he says. “The end result of this is a different way that government delivers.”

Art that connects to place

But first we have to achieve a community consensus on how the Inner Harbor and environs ought to look and feel and be used. That’s what Mark Goldman hopes these public meetings will achieve, and it’s part of the reason he invited his brother Tony to be Saturday’s second speaker.

“We like to work with zealous nuts, in the best sense of the word,” says Fred Kent. “And Tony and Mark Goldman are zealous nuts of the highest order.”

Art and Inspiration

In addition to the two speakers, Fred Kent and Tony Goldman, “Aspirations and Inspirations: Imagining the Buffalo Waterfront” will showcase the work of three local artists. Architect and sculptor Dennis Maher is constructing an installation made of “residual matter”—typically discarded construction materials—that invites viewers “to re-imagine a place that has long been cast-aside.” Puppeteer Michele Costa will present a work of mask, mime, and puppetry set to music and her poem titled, “The Edge of Here.” And Bryan Wanzer will present a waterfront soundscape.

Tony Goldman is the founder and CEO of Goldman Properties, based in New York City. Like his brother Mark, Tony Goldman is a dedicated preservationist and a believer in the ability of art to transform public spaces. Last month, the National Trust for Historic Preservation presented him a lifetime achievement award for his sensitive, creative, and place-driven development work in SoHo, South Beach, Philadelphia, and Boston.

“My approach there is going to be what is possible in the big picture and then what’s the strategy to get there,” Tony Goldman says. “My role is to outline the possibilities and to expand the thinking way beyond what was placed on the table.”

He thinks that the proposals made by ECHDC and its predecessors lack any real connection to the place itself and to the city’s industrial history. “What was offered at the table was something that had no sense of place—it wasn’t even in the conversation,” he says.

“I think Mark’s purpose in stopping this thing and reviewing it in the public arena is a most appropriate action for a concerned citizen, an active member of a public body—to stop what is too often happening in government, which is an easy, old-school model of inappropriate and obsolete ideas.”

Mark Goldman will take Kent and his brother on a tour of the city’s waterfront, and Tony Goldman imagines that at that point he will begin to formulate ideas for what might be achieved there. But whatever he proposes, he says that it will have a strong, central public art component. And the public art component should celebrate the city’s history, its diverse populations, its architecture, its environment. “Buffalo, like all cities, should be proud of what it is,” he says, because when city’s lose pride in themselves, they allow themselves to be remade in the image of something they are not.

“Cities are really scared of bottom-up planning because they lose control,” Kent says. “New York City has no bottom-up process, it’s all top -down. But then you go to Baltimore or Houston…Amsterdam has switched gears. Austin is good.

“If the people lead, the leaders follow. That’s where the zealous nuts come in.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n44 (Week of Thursday, November 4) > Aspirations and Inspirations This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue