The MARK 10 Group Show at Artspace

by J. Tim Raymond

Leaving Their Mark

Anchoring the downtown Main Street corridor for the cultural arts is the Brietweiser Building, late of a major printing firm, still later of the American Electric Car Company, but most recently repurposed to provide both subsidized housing and studio space to Buffalo artists of all disciplines. Currently the abundant gallery facility is exhibiting the work of the NYFA MARK 10, individual visual artists that reside beyond the five boroughs of New York City living and working in Western New York. The New York Foundation for the Arts MARK (which is not an acronym), in its fourth year, is uniquely designed as a professional development program for working artists regionally to increase the visibility of creative practice, advance career opportunities, and get a handle on finances. The Artspace exhibit is a group show comprising the work of the program members chosen for the 2010 seminar series. They are an especially close-knit group and have mounted a first-rate presentation at Artspace.

Art is for the maker of it, often a private journey down an uncharted path suddenly but infrequently illuminated by something like parachute flares. With skill and some luck, that path may lead to greater potential, achievement, and reward. In a group exhibition, the viewing public sees in the artists presented a single edition of an imagination, witnessing the work as a signpost pointing the way to further interest in what the artist may create in a solo future venture. These artists satisfy that experience.

Bruce Philip Bitmead has two concurrent exhibits, the eight paintings in the MARK show and a series of works at Starlight Studio and Gallery. He has become one of the strongest painters in Buffalo exhibiting today, both in the act of painting and the impact of his image. In the Artspace show, working within his self-imposed limit of color palette and subject matter, he paints houses as mute, fixed characters in architectural scenes calling to mind a longing for refuge and a sense of distance from safety at once. His figurative pieces are visually heavier, going with the brushload weighted in strokes as thick as plaster or, in another likeness, icing. But there is nothing confectionary in Bitmead’s slathered, faceless figures. They appear as visionary spectral allusions to human form, gesturing, in motion, blurred, unfocused, as if the image is physically incapable of rest.

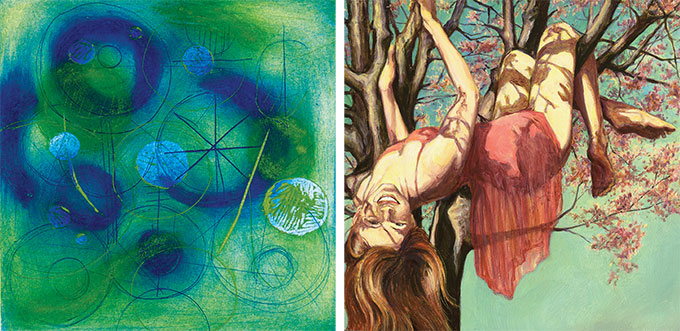

Kathleen Sherin presents a series of prints in her continuing investigation of organic forms in mono-print. These works, subtle and nearly monochromatic, flow from one to another in a natural evolution of interrelated elements in striated layers of ink applied in a non-traditional printmaking technique called “carborundum,” in which the material gradients of tone and texture allow an artist to create an image by adding light passages to a dark field.

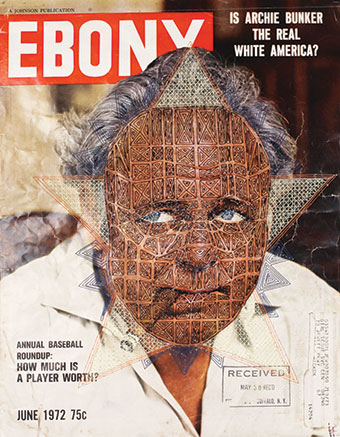

The MTV generation had gradually moved from disco, to punk, to rap and hip-hop. The popularity of the latter musical form created its own social culture, codes, signs, and fashion around the phenomena most accessible to a general audience in the TV show Cops where the individual sprawled across the hood of a police cruiser was often fashion forward, until the clothing of designers such as Tommy Hilfiger were so visually familiar, those arrested on camera became known as “Tommy Perpetrators.” Surrounding issues of social consciousness, racial politics, and the rise of street (read black) fashion, came the high profile of “Gangster Capitalism,” with the same moral investment of global economics, and most immediately familiar in the posed smug and scowling faces of Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls, the iconic characters of Brian Kavanaugh’s youth. In the image of “Biggie” and “gangster chic” the viewer may get a sense of the artist’s formative influences for his present series of collages on view at MARK 10. Kavanaugh’s sense of how to position an image, what to add where, approaches the omniscient as if someone all-knowing and unseen had arranged the visual elements of awareness to create an interlocutory dialog with the viewer. His use of delicate handwork over album covers, vintage magazine covers, posters, and photographs allows a viewer space in imagination to fill in the enigmatic possibilities of coherence.

The West Coast artist Ed Ruscha, another strong influence on Kavanaugh’s art, especially in the nuances of conceptualism, is evident in the subtle sense of relational exposition found in the long piece, Legalize. Using a color travel poster of the Grand Canyon with the text of the work in the specific colors of Southwest Airlines, Kavanaugh references the recent polarizing political positions on border crossing and immigration and a sense of the gulf between those extremities, not to mention the situational ethics of low-cost airlines 30 years after deregulation. In the tradition of artists such as Ruscha, and to some extent the German artist Hans Haacke, Kavanaugh creates his conundrums of art pieces, as he puts it, “as a sandwich between the artist and the viewer,” providing a space for interpretation and allowing each a role in deliberating these thoughtful works.

In her piece Cotton Gin, sculptor Oreen Cohen holds forth with a conglomeration of cast-off industrial refuse loosely resembling an antique machine. In preparation for her exhibit she cautioned there would be “welding going on” and managed to bring out the Buffalo Fire Department when the smoke alarms went off. Cohen’s set piece sum of parts is positioned for maximum curiosity as visitors to the exhibit view the installation nearly expecting it to spring into life. Cohen’s structural vocabulary formally alludes to a 19th-century farm machine but moves past that assessment to a wider interpretation concerning societal mores, basic survival skills, and even the subculture known as “steam punk”—industrial parodies reminiscent of the films of Hayao Miyazaki, the great Japanese animator, and invoking an era of steam power in art forms such as science fiction or fantasy featuring anachronistic technology.

In Gary Sczerbaniewicz “parasitic” architectural installation, a gray-painted wallboard construction built into the nook under the gallery’s lower staircase encloses a tapered crawl space that leads to a shrouded TV monitor screening a looped scene of a man moving through spindly trees, giving the appearance of an individual’s endless trek in suit and tie. Upstairs, his exhibit explores the same scene through another portal, featuring a crawl space leading to a point where the viewer may peer down into a shaft to apprehend the same harried man advancing ad infinitum. Sczerbaniewicz’s recent work at the C. J. Jung Center also examined the theme of tunnels, shafts, constricted spaces, and human endurance facing oppression and confinement.

Dorothy Fitzgerald presents four large, sensual, expressionistic paintings she describes as if they were conversations with her best friend without abridgement or judgment, a “safe place” to express herself. Her brushwork paints depictions of figures, personal objects, and narrative segments with patterns of crochet.

Amanda Besl contributes one single painting. It is compelling subject matter: On her back a young woman stares out of the frame, her cropped torso accompanied by a baby rabbit she holds between her breasts and a muscled sleeping whippet curled at her shoulder. Besl explains the figure signifies the uncertain transition from innocence to self-awareness in an adolescent girl’s passage to adulthood. Her exploration of female animal nature awakened through contact with animals of power and harmlessness engages the viewer to witness fleeting glimpses of a guileless child in the effortless gaze of a budding seductress.

Kate Parzych’s series Water Marks are large color photographs of water in various depths of field, from a view out the window of an aircraft of sailboats at 20,000 feet to the tide’s edge on a shoreline walk. Her images vignette the water’s surface in cropped views of “peaceful moments” that are often overlooked.

Catherine Schuman Miller creates stylized images in a series of prints using line drawing in simple patterns and symbols on fields of muted reds, greens, and orange for a display that hold the walls with elegance.

Timothy Frerich has organized his investigation of “transitional areas” into four panels clinically detailing the evident community-polarizing positions surrounding the location of such controversial “green energy” projects as the proposed and delayed New Grange wind farm located near Fredonia.

The MARK 10 exhibit closes this weekend.

—j. tim raymond

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n16 (Week of Thursday, April 21) > Art Scene > The MARK 10 Group Show at Artspace This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue