Next story: Malcolm Bonney's artwork at the Remington Rand Buidling

Work by Lin Price and Robert Booth at Buffalo Arts Studio

by Jack Foran

Go Figure

The current show at the Buffalo Arts Studio reprises a frequently asked question by art audiences: What does it all mean?

The show consists of paintings by Lin Price and small sculptural figures by Robert Booth. In both cases, devilishly perplexing as to just what the artist is trying to tell us. In some works, to the point you suspect the artist himself or herself isn’t quite sure.

What modern art—particularly abstract art—established was that it isn’t necessarily the artist’s job to tell us what he or she is thinking, what the art means. What it means is more what it means to us. The artist’s job is to make it meaningful.

But non-abstract art—figurative art—seems to pose the question again. What does the art mean? Because figurative is narrative, by and large. And narrative—a story—has to make sense. Or it’s something else, not narrative. (Not to impose anything on anybody. Not to straitjacket anything or anyone. But it’s a condition of story to make sense. Like a condition of painting is color, a condition of sculpture three dimensions. A condition and expectation that modern art plays on, challenges, sometimes undercuts, but can’t really annihilate. Because it’s a condition. The nature of the thing, you might say.)

Both artists offer notably figurative art that nonetheless bewilders. Such as Price’s painting Rare Bird, showing a man and a bird on a tree branch, the bird seemingly part hawk, part parrot, maybe part something else, the man with his eyes closed as if in meditation or reverie, and cradling in his hands, against his chest, a very large bone, like a small dinosaur bone.

Or one called Natural Disaster, showing the same man as in the Rare Bird and many other paintings—the artist’s husband, apparently—standing fully clad in street clothes in a pool of water just about to cover his shoes, the water emanating from a standpipe and spigot that looks like it could be shut off as easily as not, but is not.

Other works make a little more sense, like Push and Pull (for Hans), divided top and bottom into two distinct segments, the top segment showing the man again pulling—or attempting to—a vacation house trailer, the kind meant to be pulled behind a car or small truck, with a huge rope or chain, the bottom segment several dung beetles pushing huge—three times their size—balls of manure.

There’s a connection, but just a connection. Partly the deal is like that with abstract art. The audience has to complete the work. But what’s the story? The real connection? Okay. Push and pull. But so what?

Most of the works seem deliberately—even a little perversely—to frustrate rather than suggest a comprehensible narrative.

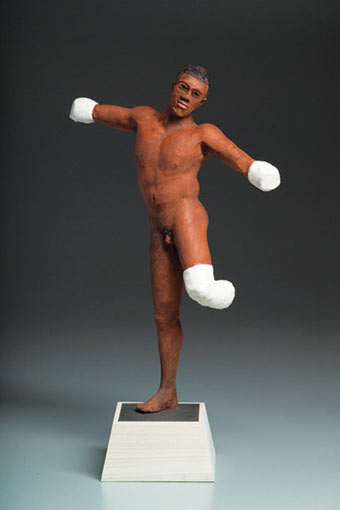

Robert Booth’s little human figure statues fall into three basic categories, the artist explained briefly at the opening.

First, the ordinary and everyday, of people often in slightly awkward moments and poses, such as when just getting out of the shower, half wrapped in a towel, half naked.

Second category, war, or more precisely, it seemed, the aftermath of war, such as a statue of a man balancing on one leg and bandaged foot, the other leg and both arms bandaged stumps. Entitled Raymond: a Good Dancer before the War.

The third category he did not seem to explain so clearly. (Or I missed it. But I was listening.) Of figures in situations or with attributes unusual to the point of bizarre. Such as several what you might call pincushion or porcupine statues (or St. Stephen comes to mind) stuck all around the upper body, neck to belly, with a few dozen needle-like wooden sticks. Maybe something about acupuncture. Extreme acupuncture. Or one showing a woman emerging, a bed pillow in each hand, from a carpentered opening in the top of what looks like a birdhouse. What?

You’re on your own.

The Lin Price and Robert Booth exhibit continues through July 30.

—jack foran

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n27 (Week of Thursday, July 7) > Art Scene > Work by Lin Price and Robert Booth at Buffalo Arts Studio This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue