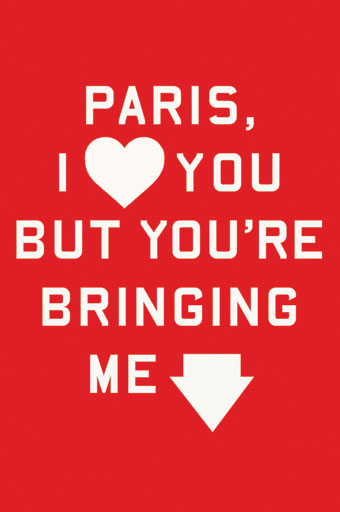

Paris, I Love You but You're Bringing Me Down

by Woody Brown

Here is the money. Thank you, goodbye.

Paris, I Love You But You’re Bringing Me Down

by Rosecrans Baldwin

Farrar, Straus and Grioux, April 2012

It would have been so easy for Rosecrans Baldwin to go so wrong in writing Paris, I Love You But You’re Bringing Me Down, a sometimes funny, sometimes hapless, and mostly entertaining account of the 18 months the author lived in Paris. This is his second novel-length publication, and much of it deals with the misfortunes and hard-won joys of writing and finally publishing his debut novel, You Lost Me There, which, it’s worth mentioning, received some very good press (including a strange plot summary billed as a review in the New York Times). But think of the blurbs we could write—“Young white bourgeois writer travels to Paris to find the words for his first novel…and ends up finding himself.”

I am happy to report that Paris rejects stickysweet selling point summaries like that from the very first page. Baldwin has his own purposes for this narrative and he uses a unique and dexterous voice to tell it. That voice, which thankfully avoids the senseless snark that so many writers use to hide any sort of emotional vulnerability, is refreshingly honest, frank, and, most interestingly, ambivalent. Ambivalence is the name of the game here. Readers will notice that many of the book’s sections, which in turn comprise the 51 short chapters, end with curious little moments of ambiguity. Kind of like the narrative equivalent of small, ornately wrapped presents that seem to have words written on them, but which words are too small to read. The reader feels like there should be a clear, unambiguous meaning to the text, some point (“This was good!” or “This was not that sweet!”) that he should be able to read. But there isn’t, and that’s a big reason why this text is worth reading.

Because, you know, think about it. Would it be interesting if it were simply called Paris, I Love You and all Baldwin did was talk about how much he loved Paris? Or how about if, conversely, he called it Paris, You’re Bringing Me Down and all he did was complain about how much the city disappointed his expectations? In fact, Baldwin discusses this latter reaction (which apparently is actually called Paris Syndrome) as part of what is finally an endearing and honest account of his experience living with his wife, Rachel, and working at an advertising firm. This account includes compelling sketches of real-seeming people, each European in a way that is at once what the American reader expects and also more informed than simple stereotype. And anyway, the point is that no, neither of those options would be as interesting as the text in question.

Speaking of Rachel, her presence in the book was one of the main things that nagged at me after I finished it. Her stories end several of the chapters and these stories are some of the best, but other than that Baldwin gives her short shrift. I could tell, though, that he didn’t want to. He seemed dead set on proving that he hadn’t done what he apparently had—that is, move to Paris for a job and force his wife, who does not speak French, to spend her days and many of her nights alone and unable to communicate. He clearly sympathizes with her, but there seems to be no way around her loneliness. Indeed, I found it hard to follow the narrator on his luxurious outings to Switzerland and the Bahamas without thinking of Rachel languishing in the dim apartment back in Paris.

But my point here is that Baldwin’s ambivalence toward Paris lends the text its authority. He has no clearly discernible agenda other than to describe what it was like for him living there. And that is good, that is why I love travel writing. Travel writing is relentlessly interesting to me, but for it to be successful the author must be a kind and caring guide, one whose voice is enjoyable to hear. Baldwin achieves all of this. We wouldn’t read Dostoevsky’s Winter Notes on Summer Impressions (1863) for any sort of actual information about Paris because this is how he describes Paris: “I will not say exactly what I have looked over, but to make up for it I will say this: I have formed a definition of Paris, attached an epithet to it, and I stand by that epithet.”

And so of course you may be thinking, “Yeah, Woody, we get it. But Dostoevsky was clearly doing his own sort of thing in Winter Notes, like for instance purposely not doing exactly what you expect him to do.” True, but I would submit that a ton of travel writing, without any irony at all, actually makes the same gesture that Dostoevsky jokingly makes; the gesture being the promulgation of a simple (usually preconceived) positive or negative reading of an entire city, or country, or people. For instance, I might have an interest, based on my own brief stay in Montmartre, in telling you the story of how I was accosted by Hasidim on the Boulevard de Rochechouart screaming “C’est Juif?!” (which actually happened), and using that story to justify some sort of complaint I have about the whole city as a result, which is of course not the case. But my point is it could be the case, and Baldwin has more than enough ammunition to load a Francophobic six-shooter and fire away.

What he does instead is write (and write well) an engaging, sympathetic, and entertaining book. Baldwin won’t win any awards for depth of intellectual analysis, but he will certainly win over most readers with his adroit and economical prose, his observant eyes (the way he talks about his friends and coworkers, namely Lindsay, Bruno, Pierre, and Asif, is loving and careful), and (I can’t believe I haven’t mentioned this yet) his sense of humor. His description of the typical American tourist’s experience in Paris late in the book, from which comes the title of this review, also relates hilariously a pretty good approximation of, for instance, the circumstances surrounding my purchase of a snifter of calvados that cost 16 Euros because I desperately had to use the bathroom and the bartender at this fine establishment wouldn’t let me use the bathroom unless I bought something and outside la tempête Xynthia was raging with what seemed like a personal hatred for my bladder. Or also consider Baldwin’s story, which I hope with all my heart is true, about his interview with Sean Connery, during which the latter, in response to the question, “If Edinburgh were an actress, who would she be?” said, “Edinburgh, I think, would be an actor, and he would be me.”

Did I mention Baldwin is a good writer? The text is filled with pocket-sized prose hors d’oeuvre, fine little bits of fioritura that are a real delight to read: “The sun above Paris was a mid-July clementine,” for instance, or, “drivers sat in traffic, huddling inside their cars with the windows closed, or cracked open with a cigarette protruding like a snorkel.” These ornaments adorn the text in smart, understated ways. The whole thing finally works and works well as what it is: a charming, funny, warm, and sort of shallow account of life as an American in Paris. Yay. You should read it. Further reading should of course include Stephen Clarke’s novel A Year in the Merde (2004), which was recommended to me by a man whom I met in Paris named Djordje Djokic, and maybe Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast (1964). But mostly the first one.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n24 (Week of Thursday, June 14) > Book Reviews > Paris, I Love You but You're Bringing Me Down This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue