Revenge, Horror, and Shakespeare

by Anthony Chase

Titus Andronicus reading for Shakespeare in Delaware Park

On Sunday, Shakespeare in Delaware Park will host a reading of Shakespeare’s very first tragedy, Titus Andronicus, at the Buffalo Seminary. Saul Elkin, founder of the festival, will play Titus, a fictitious general from ancient Rome who finds himself in a bloody battle of revenge with Tamora, queen of the defeated Goths. Lisa Vitrano will play Tamora.

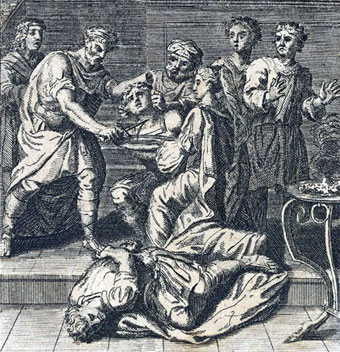

Before the play is over, Tamora’s degenerate sons will ravish Titus’ daughter, Lavinia, cut out her tongue, and chop off her hands to keep her from bearing witness. Lavinia will outwit them by revealing that she can read and will write her attackers’ names in the sand with a stick. Titus will kill the young men, bake them into a pie, and feed it to their mother.

The reading is annual autumn fundraising event for Buffalo’s popular Shakespeare festival.

This is the third year I will have staged an abridged version of a lesser known play by Shakespeare for this event. Last year we did King John, and the year before Cymbeline. These specific plays were chosen because none has ever been performed in Delaware Park. The event is catered by Rich’s Catering, with wine tasting by Leonard Oakes Estate Winery.

As we take a look at Titus Andronicus, a definitive Elizabethan revenge tragedy, it is interesting to remember that the most successful play of the Elizabethan era was not by Shakespeare at all. The Spanish Tragedy, a revenge play by Thomas Kyd, holds that distinction. Its language was vivid and thrilling, and its plot was marvelously theatrical and violent. The Spanish Tragedy predates Titus Andronicus by just a few years.

In The Spanish Tragedy, a ghost has been dishonorably killed and requires revenge. The central character feigns madness and stages a play as a way to catch the murderers. (Now where have we heard that plot before?)

Kyd used the bloody Roman tragedies of Seneca as his model, and other revenge tragedies of the period followed suit, Titus Andronicus (and obviously Hamlet) among them. In tapping Seneca for inspiration, Kyd struck a reverberating chord in the Elizabethan consciousness. Seneca depicted thrilling scenes of onstage violence, employed soliloquies as a means to divulge secrets to the audience, and reveled in the use of ghosts and the supernatural.

Italian playwrights of the period followed neoclassical rules of verisimilitude and decorum, and despised the use of violence and supernatural characters. They even frowned upon plots that moved from place to place. Snore, bore! By contrast, the freewheeling Elizabethans couldn’t get enough of this kind of stuff!

Shakespeare’s audience was thrilled by Seneca’s notion that when someone is wronged, revenge must surpass the original crime. This idea is given free reign in Titus Andronicus. We watch Titus’s woeful suffering and the horrible violation of his daughter, and as an audience, we endorse his macabre and theatrical revenge. As with today’s horror films, a bit of giddy good humor often accompanies the hacking and slashing.

Through his influence, Seneca gave credibility to commercial theater in Elizabethan London. If ghosts, asides, soliloquies, and bloody violence were good enough for the Romans, they were good enough for the Elizabethans! Contemporary audiences adored the elevated language and bold theatricality of revenge plays like The Spanish Tragedy and Titus Andronicus. Indeed, playwrights who were more highly respected than Shakespeare during his lifetime, like Ben Jonson and even John Fletcher, had to concede that he was spectacularly popular—a phenomenon that they found perplexing. One lesser playwright, observing Shakespeare’s ascending popularity, described him as an “upstart crow,” in 1592—soon after Titus Andronicus was first performed.

Of course, this passion for Senecan revenge plays emerged at a specific moment in English history. At a time when the more enlightened rule of law was replacing the medieval rule of violence, revenge tragedies allowed audiences to indulge is a delightfully forbidden fantasy. In this new era, when a person was wronged, justice was to be carried out by the state, not the injured party. What fun is that? Especially during Halloween week, when we are inundated with horror films, it makes me think about the role that horror films with their supernatural threats and terrifying villains serve today.

We have 400 years of hindsight when thinking about Titus Andronicus. The Tudor monarchs were the last in English history to achieve the throne on the battlefield. Medieval England was a recent memory. Elizabeth’s grandpa had defeated Richard III in the Battle of Bosworth Field. By contrast, Elizabeth maintained her crown through her wits and the rule of law. Titus Andronicus combines wit and bloody revenge—how delicious!

Recall that Elizabeth also managed to elude assassination and military advances against her. Just a few years before The Spanish Tragedy and Titus Andronicus, in 1587, Liz had repelled efforts to end her reign by executing her cousin, Mary Queen of Scots. The Catholic Church and Spain considered Elizabeth to be her father’s bastard daughter, and preferred her Catholic cousin, Mary. In the year following Mary’s execution, King Philip II of Spain (Elizabeth’s former brother-in-law) sent his armada to overturn her. Again, Elizabeth trounced the advance, defeating the Spanish Armada and establishing herself as Europe’s most powerful monarch. It’s like the plot of a Shakespearean play!

Another element of Titus Andronicus that would have thrilled the Elizabethans was the plot twist that comes from Lavinia’s ability to read and write. There had been a surge in literacy in England since the introduction of the printing press, but only among men. A woman who could read would have provided a plot reversal as unexpected as the sex switch in The Crying Game.

Of course, Shakespeare being Shakespeare, in Titus Andronicus we see a more sophisticated treatment of the revenge theme than in The Spanish Tragedy. Thomas Kyd’s characters are two-dimensional, but with Shakespeare, every minor person seems to walk onto the stage from a fully dimensioned offstage life. In Titus Andronicus we meet Tamora’s nurse, fearful for the life of her mistress, whose marital infidelity has been betrayed by the birth of a mixed-raced child; she has a single scene, but seems like a real person. We meet Aaron the Moor, Tamora’s secret lover, who would seem to be evil personified, except for his pride and love for his child. We meet a dim-witted pigeon-keeper, who gives Shakespeare a chance to offer a darkly humorous twist on the “kill the messenger” cliché.

The distance between Titus Andronicus and Hamlet was less than ten years, yet in that expanse of time, we can see his thinking on the topic of revenge has evolved. In reworking the details of The Spanish Tragedy in Hamlet, Shakespeare writes a play that questions the ethics of revenge itself. Hamlet recognizes that in carrying out revenge, he will descend to the level of Claudius. Titus, a military man, has no such hesitation. By the time Shakespeare writes The Tempest, just before his retirement, Prospero has an entirely evolved view of revenge; that play ends with forgiveness, reconciliation, and the unification of marriage.

Staging plays for the fall fundraiser at Shakespeare in Delaware Park requires me to engage in deep if judicious editing. I have no compunction about this. Even in Shakespeare’s time, the plays would have been cut significantly. Hamlet, for instance, would be fully five hours long if performed in its entirety, and yet we know that an Elizabethan play was allowed just “two hours stage traffic.” Large expanses of the play we know as Hamlet today were never performed for Shakespeare’s audience. I have, therefore, happily endeavored to shape an entertainment of that duration, with wine, desserts, and coffee included for the Shakespeare in Delaware Park fundraiser.

In addition to Saul Elkin as Titus and Lisa Vitrano as Tamora, the cast features Susan Drozd as Lavinia, Peter Palmisano as Marcus Andronicus, Greg Howze as Aaron the Moor, Jonathan Shuey as Quintus, Jeffrey Coyle as Chiron, Jacob Albarella as Demetrius, Matt Witten as Saturninus, David Hayes as Bassianus, Dave Lundy as the pigeon-keeper, Kelly Ferguson as Tamora’s nurse, Geoff Pictor as the Goth messenger, Steven Vaughan as Aemilius, and Lisa Ludwig as the narrator.

The Buffalo Seminary is located at 205 Bidwell Parkway. Wine tasting and hors-d’oeuvres are at 6pm. The reading begins at 7pm. $55 admission ($50 for SDP members). While the event is basically sold out, you can try to negotiate a ticket by calling 856-4533.

It promises to be a delightful event. If we’re lucky, we might even have pie!

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n44 (Week of Thursday, November 1) > Revenge, Horror, and Shakespeare This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue