Next story: For the Non-Artist: A Case for Taxpayer Support of the Arts

Coffee For Two, Pistols for Four

by Mason Winfield

Dispatches: The War of 1812

October 8-9, 1812-

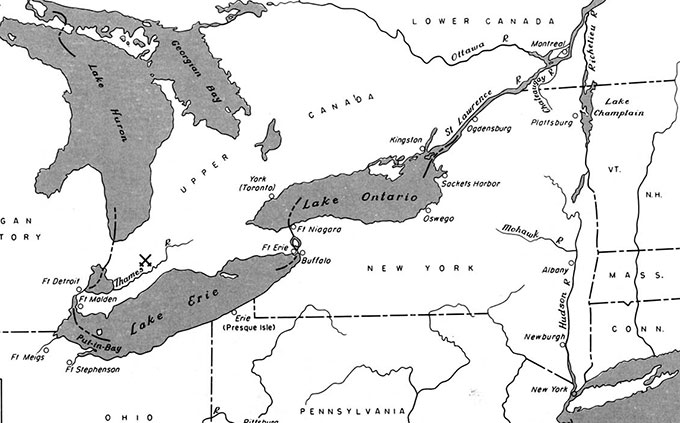

It may shock anyone to envision America undersupplied, but when the 1812 war was declared, the whole US had a standing army of 7,000. There were almost that many redcoats in Ontario, and 100,000 elsewhere. As far as artillery on the Niagara, the US was outgunned 100 to none, and it had no warships. Ship rustling, hence, could be big business.

In August 1812, Western New Yorkers had been treated to the spectacle of American prisoners of war being marched, shoeless and struggling, on the high trail along the Niagara to Fort George. Folk in Lewiston could hear the wounded groan. America needed a win, and pressure was intense on the Army of the Niagara to deliver it.

In early October, 1812, two British ships, both brigs, rested in the water only yards from Buffalo, safe under Fort Erie’s cannon. One was the Caledonia, a fine warlike vessel built at Fort Malden, Ontario. The other, the former Adams, was an American ship taken by the British at Detroit and renamed. (This second brig is called the Detroit in many histories.) They held heavy guns, US prisoners from the surrender at Detroit, and maybe even a load of pricey furs, or so Seneca chief Farmer’s Brother let on. His Buffalo friends looked over the river with greedy eyes.

Twenty-seven-year-old Lake Erie commander Jesse Elliott planned on leading a secret, late-night, 50-man mission to storm the British ships. He addressed the ranks, calling only for volunteers “brave and discreet” since “so much depended on their coolness.” So many Yankee cool-guys stepped forward that Elliott couldn’t take fewer than than 60, in some accounts 100.

The Americans filled two big rowboats on the Buffalo Creek, each man with a favored close-quarters weapon, often a stubby saber called a cutlass, and other provisions: “Coffee for two and pistols for four.” Both are explicable. In the flintlock era no gun shot twice without reloading. If you planned to shoot fast, you needed a lot of guns. And coffee was thought a bracing restorative with even medicinal properties. May the brew have stayed hot. October 8, 1812, was one of those clammy, drizzly days the Niagara knows well.

At midnight the raiders headed out Buffalo Harbor. There Lake Erie opens south into a virtual ocean. They rowed miles out to fool any sentries, then came back along the Canadian side and hovered without even speaking for hours. It was 3am when they closed on their targets.

Sentries on the ships set up a hallooing. The Yanks called something back that wasn’t suitably cool and took a few shots from small arms. Both squads threw up grappling hooks and hauled themselves on deck.

Lieutenant Elliott was among the first aboard the Caledonia. Its captain welcomed him with a cutlass blow that halved his hat. Robert Irvine, a young Scot, fired a blunderbuss into the Americans and was dropped by a sword stroke. After a 10-minute fight, 70 British went below decks and 40 prisoners came up. The Americans looked over their prizes and readied to make waves.

The Caledonia’s cannon were loaded, but no ammo was in sight. The British second mate was brought up to find it. They were “fresh out,” he explained. Someone—perhaps Dr. Cyrenius Chapin—displayed a cutlass and proffered its services for an impromptu vasectomy. The mate’s memory was refreshed. The rest of the ammo and all cannon were hauled to the fort side of the ships.

Fifty yards of water and dark air away, Fort Erie was ominously still. Once the rickety ships moved the adventure started again. The fort cut loose with its first load of iron fired in any war. (“Whiz comes a shot over our heads!” chortled American Isaac Roach in his memoirs.) A mounted American major in Black Rock fell dead. The Caledonia’s six-pounders roared back.

The first plan of the American strike teams was to get their prizes into Lake Erie and out of range of British guns. But the quick risk and long safety of the US shore loomed straight ahead. They made for it.

Both ships were hit several times and set on fire. The Caledonia was dowsed at the naval base at Black Rock, the riverside village named for the gigantic stone that once stood along the river at the foot of Porter Avenue. The Adams ran aground on Squaw Island, and the commandos jumped out and ducked. Some “Green Tigers,” members of the British 49th regiment, crossed over and boarded her, but American soldiers drove them off. Fort Erie’s cannon vented on the Adams all the next day. Bits and pieces of that barrage, people say, still turn up on Squaw Island.

The action had been a plus-three to the US cause: Elliott’s commandos had taken two warships from the British and added one to the American side. And 11 months later this Caledonia would turn the day for the US in one of the pivotal battles of the war.

Mason Winfield is the author of 10 books, including Ghosts of 1812 (Western New York Wares, 2009), the only recent history of the 1812 war on the Niagara.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n47 (Gift Guide, week of Thursday, November 22) > Coffee For Two, Pistols for Four This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue