Byron Rich's Installation at Big Orbit Gallery

by Jack Foran

Benign Nor Hostile, Merely Indifferent

Byron Rich’s new art exhibit at Big Orbit is already over. Dependent as it was on some basic life forms supplied with a limited nutrient stock. But you can check it out on his website, where it is documented along with a dozen or so of his previous projects. The website is byronrich.com.

The work is called Benign Nor Hostile, Merely Indifferent. The laconic-to-a-fault aspect of the title is a kind of unfortunate signature quality of this artist. Why not Neither Benign…? It’s fine to let the artwork speak for itself. But this complicated, technology-fraught, interesting work needs some words to go with it.

Checking out the previous works helps, too. Particularly one called Protista Imperialis, which was shown at UB last year. It was about interaction between humans and the physical world, particularly the infra-human primitive biological world. But interaction that you wouldn’t suspect. In the Protista work, algae in Petri dishes was configured in the shape of the world’s continents, within a field of a high-frequency tone that was found to impede the growth and ultimately life of algae. However, motion-sensing equipment set to detect human activity around the piece—presumably indicating human interest in the piece—suppressed the high-frequency tone. Thus, human observer interaction promoted growth and sustained the life of the algae. (Tough luck for the algae for the 16 hours a day or so when the UB gallery was closed.)

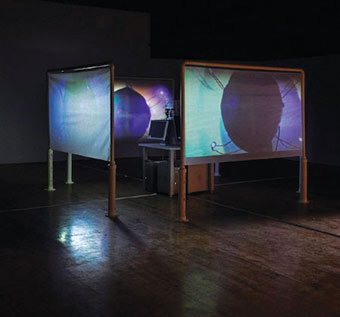

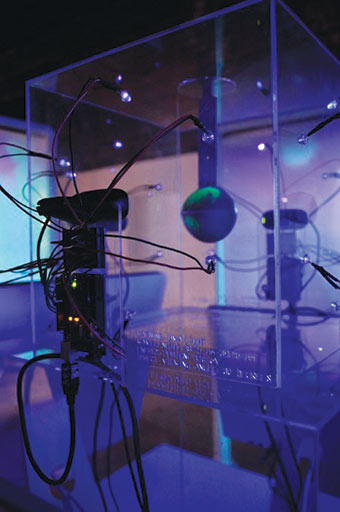

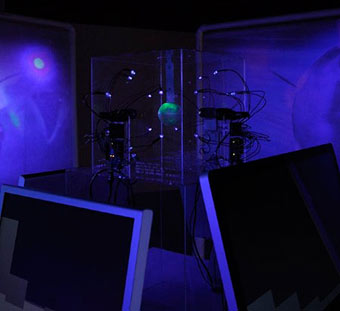

In the Benign Nor Hostile piece, two different strains of E. coli bacteria—one that shows up red under ultraviolet light, and one that shows up green—were applied to a ball of agar nutrient and allowed to fight it out for dominance. And survival, until the agar was consumed, which took about a week. The human interaction in this case was audible noise, which triggered ultraviolet LED lights positioned around the ball, which illumined the agar ball and revealed the progress of the red versus green contest, and allowed four video cameras to capture an obscure mix of images of the centerpiece apparatus and ghostly overlays of the humans interacting, which mix was projected on four screens surrounding the apparatus and audience.

The later work only seemingly less human interactive than the former. In the Protista piece, the human interaction affected the growth of the algae. In the Benign Nor Hostile, the human interaction merely caused illumination, enabling observation and video capture and projection. But so, what is called “observer effect.” To observe is to affect. More subtle interaction.

Rich’s artwork is about humans, nature, and technology, three different worlds that often seem mutually hostile, but don’t have to be, he seems to be trying to say. But there’s usually the idea of a contest, a struggle. Sometimes a rather deviously rigged contest, on the part of the human element, employing technology, against nature. As in a piece called JM101-Distance, involving some E. coli on agar in a Petri dish, and a computer program that tracked its growth on the agar, and as the E. coli grew, projected increased amounts of light of a wavelength harmful to the bacteria. So that as it grew, it grew its destroyer.

But the larger point seems to be simply co-existence. For any one or two of the three elements to try to dominate any other element is folly (humans, with their penchant for control, and technology, with its superhuman potentialities and indifference to either humans or nature, are the usual suspects here). One of his works involved clandestine procurement of swab samples from nooks and corners of the Farnsworth House, the Mies van der Rohe icon of “clean” modernism, to reveal mold and bacteria that secretly inhabited the structure, and in a sense “humanized” it in a way that the “largely de-humanizing nature of modernist architecture and the fascination with cleanliness and sterility in form and concept” (in the words of the artist) may have failed to.

A more remarkable protest work against technological sterility—or of integration of humans, nature, and technology—is called Mossy Hill, in which the artist installed a grass floor in an elevator in a seven-floor building. A companion elevator retained the standard linoleum or whatever floor, but people voted with their feet overwhelmingly for the turf model. Some users took their shoes off, to better luxuriate in the unexpected encounter with the green world. Some stayed on board beyond their intended destination, for a half hour or more.

Interesting work, all in all. It will be interesting to watch where it goes.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n15 (Week of Thursday, April 11) > Art Scene > Byron Rich's Installation at Big Orbit Gallery This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue