I'm Not a Juvenile Delinquent

by Woody Brown

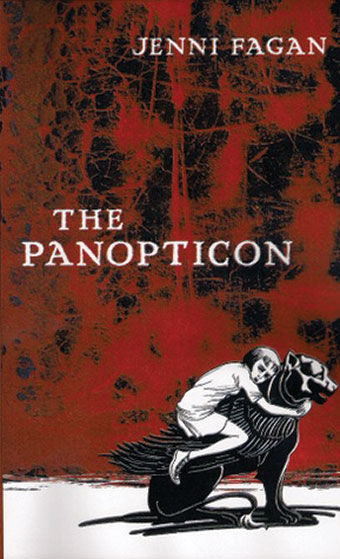

The Panopticon

by Jenni Fagann

Hogarth, July 2013

The title of this article is the name of a song by Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, a song that contains the line, “Do the thing that’s right / and you’ll do nothing wrong.” (This line is sung of course by Frankie himself, whose own juvenile delinquency would result in his untimely death from a heroin overdose at age 25.) This tautology is an apt condensation of the commands society issues to the “clients” of the Panopticon, the eponymous compound that is the backdrop for Jenni Fagan’s beautiful, brutal debut novel. Each of the wayward, semi-incarcerated juvenile offenders in the Panopticon lives her life without any privacy, in full view at all times of a giant central watchtower with tinted glass. The authorities demand that they stop breaking the law, but the children (and they really are children) contain within themselves enormous unknowable tragedies and long lists of abuses and misfortunes; in short, mitigating circumstances that the courts do not recognize. Their crimes, the reader learns, are the sharp tips of vast icebergs. Fagan, a justifiably decorated young writer, has written a novel that testifies beautifully to the insoluble value of every human life, even the life lived by the lowest of the low.

Enter Anais Hendricks, a 15-year-old orphan, addict, and career criminal. It is through her voice that Fagan gives us The Panopticon. It is a remarkable text that is founded on the author’s sustainment of the discord between the sweet and the disgusting, the moving and the horrifying, and the mature and the juvenile. The Panopticon performs the same irresolvable dichotomies that constitute the lives of the troubled youths that reside there. It does so with an unflinching attention to its characters’ realities, an attention that is often uncomfortably intimate and honest. Scenes of drug use, sexual violence, and general urban destitution abound, and they are juxtaposed with heart-wrenching portraits of persistent innocence.

The reader learns in the initial chapters that sometime before the narrative present Anais may have been involved in the savage beating of a police officer who has since fallen into a coma. Anais herself has no real memory of this event, which is not surprising considering the extraordinary extent of her drug use. (At age 13, for instance, she was skipping school and chasing hits of acid with hospital-strength speed.) The local police have accused Anais of the assault, however, and the prospect that the officer might die (and that Anais would therefore be charged with murder) hangs like the blade of a guillotine over the narrative.

Anais longs for some semblance of a home, some sort of privacy and comfort. Upon entering the Panopticon, she muses, “Imagine a bath—that would be too good. A great big fuck-off thing on legs with a huge window next tae it, and bubbles, and views of the sky. Imagine a bathroom like that, with fluffy white towels and a bolt on the door.”

She never knew her biological mother before the latter jumped out of the window of a psychiatric hospital; as a result of her mother’s suicide, she was placed in 24 separate homes before the age of seven. Anais often tries to repair the absence of a family by creating a narrative of herself that can serve as her own personal creation myth, a sort of basic foundational story, no matter how ridiculous or improbable, in which she can contextualize herself. She calls this “the birthday game,” and the passages in which she plays it, alone and in her bed, are some of the more moving portions of The Panopticon. But just as quickly as Anais lets her fantasies run wild, she beats them into submission: “In all actuality they grew me—from a bit of bacteria in a petri dish. An experiment, created and raised just to see exactly how much fuck-you a nobody from nowhere can take.”

Anais is one of the great lead characters in fiction since the turn of the millenium. She is smart, hilarious, sweet, troubled, hurt, strong—she embodies the polychromatic beauty of life itself. She demonstrates at times a sociopathic potential for violence, but her crimes are never totally unprincipled. In this way, she is a Romantic figure, like a mixture of Oliver Twist and Beatrix Kiddo from Kill Bill. She is at once a hardened drug addict and a child, and there is an irreducible youth in her that no amount of abuse can destroy. In one particularly endearing example, Fagan nails precisely a subtle scene of adorable adolescent blush: “He grins wider, he’s got dimples. I smile back. I cannae help it. It’s one of they awkward ones where it seems like you like somebody that way, but actually you dinnae! You’re just smiling like that because you’re a moron!”

I think Fagan should get a Pulitzer for those two exclamation points alone. The decision to write in dialectized Scottish English (e.g., “’S alright for youz tae laugh, you urnay fucking soaking!”) is an inspired one that gives the text a unique and unmistakable tone.

In the first person, plausibility is much more important than it is in a third-person omniscient narrative. Whereas an omniscient narrator needs no excuse for how he knows something, a first-person narrator is a character with an identity who is bound by the same or similar constraints as other characters who do not narrate. If Anais tells the reader something, the reader always asks if it is plausible that she knows what she knows or that she sounds the way she sounds. This can force an author to sound less poetic or writerly, because would an uneducated orphan write that well? In The Panopticon, Fagan generally manages to hit the nail right on its plausible head.

But the novel is not without its issues. Most notably, the Panopticon itself does not seem very different from any other group home for youth offenders. Though it is a literal iteration of a Foucauldian nightmare, its unique structure does not seem to affect the narrative in any significant way. Occasionally Anais will muse about how she’d like some privacy, but she and the other residents clearly still have enough privacy to use drugs, beat each other mercilessly, and harm themselves. They can also leave the compound apparently whenever they like, and with cash in their pockets. They use this cash to buy drugs that they then bring back into the Panopticon without any of the staff batting much of an eye.

Some stretches of The Panopticon are a bit of a slog. After a while I found my patience for Anais’s repeated obsession with her origin waning. Something about that did not ring true to me—that she might every night actually lie in bed and say to herself the same clichéd questions. Additionally, the plot moves little during the book’s middle except for a few exciting exceptions. I wished as I read that Fagan had focused more on the proceedings of the police department’s investigation of Anais, or on the politics of the community within the Panopticon, than on Anais’s mental state, with which the reader is already constantly familiar by virtue of the first-person narrative.

The last 100 pages, however, are extraordinary. Chapters 18 and 19, which follow the residents’ outing to a loch, are without a doubt the best in the novel and some of the best fiction I have read. They reminded me of the scene at the lake in Amity Gaige’s Schroder, which was also incredible. Most of all, the ending of the novel is utterly redemptive in a way that will bring tears to your eyes. When Anais finally says, “They cannae have this soul,” it is a stunning moment made all the more moving by its frank understatement. The text’s final pages outweigh many times over any faults that blemished those preceding, and they proclaim Fagan a powerful artist, one whose career I will now follow with bated breath.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n33 (Week of Thursday, August 15) > I'm Not a Juvenile Delinquent This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue