The Son's Coming Up

by Buck Quigley

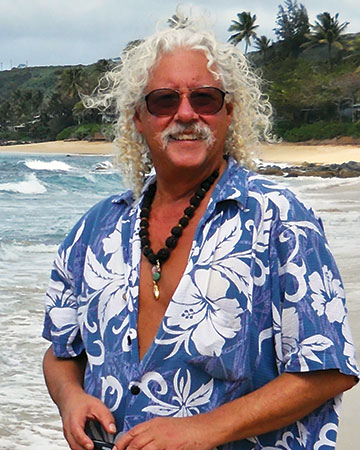

Arlo Guthrie plays Wednesday, October 16, in Asbury Hall at Babeville

7pm/door; 8pm show. $40 advance/$45 day of show.

www.babevillebuffalo.com/events/arlo-guthrie/

Arlo Guthrie brings a celebration of his father’s life and music to Babeville

September, 1967, as the country sank deeper into the quagmire of the Vietnam War, a 20-year-old folk singer named Arlo Guthrie released a humorous monologue laid over some finger picked ragtime guitar entitled “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree.” Clocking in at almost 20 minutes, the song was way too long to gain commercial radio airplay and would not even fit onto a 45rpm single. Nonetheless, the song gained popularity on non-commercial stations and the album Alice’s Restaurant rose to #17 on the Billboard chart buoyed by its catchy chorus and the hilarious narrative of a young man being declared unfit for the draft because he’d been convicted of littering after a Thanksgiving feast in a repurposed church.

Two years later the song would be adapted into a feature film directed by Arthur Penn. Speaking on the phone from his hotel room in Skokie, Illinois—where he is on the third leg of a two-year tour celebrating the centennial of his father Woody Guthrie’s birth, a tour that comes to Babeville on Wednesday, October 16—Arlo says the dark tone of the film made it “not his favorite adventure.”

“Well, the film was based on the song,” he says. “The song was only 20 minutes long. And so to make a film, which generally has to be 90 minutes, you have to make up 70 minutes worth of stuff. The stuff in the song was true and real, and the stuff that was created was fiction. It’s always been troubling that my narrative in the song I thought was fairly humorous, and the narrative they had to create for the movie was kind of dark.

“You know, it takes much more time than I would have ever imagined for the kinds of changes we were hoping for in the ’60s to take place. The part of the movie that Arthur Penn tells, he tells from a different generation than mine. He’s telling it from a sort of World War II generation. So a lot of the story in the movie is seen from that perspective. And one of the features of that landscape perspective is that this young generation is just sort of flailing around, not really having any ideas, or just enjoying themselves without responsibility—those were the kind of themes that were popular at the time that the movie came out. And a lot of that is still held over in people in positions of authority—whether they’re bankers, or investment firms or insurance companies, or arms and munitions manufacturers, or, you know, groups like Monsanto, or even into the congress and into the administration and into the Supreme Court—there is still this holdover of that perspective into this modern world. And I think it really doesn’t serve us all that well. It seems like it’s holding us back…”

AV: What do you think about the whole Occupy movement?

Guthrie: I think it’s great. And what’s great about it is that there are young people willing to become involved in the destiny of the world. I mean, that’s the first thing that’s great about it. Even if I didn’t agree with the sort of general overall philosophy—which by the way I do—but even if I didn’t, I would see it as a great thing that people are learning to become involved. And once that happens there’s a feeling of community that develops in this world where people are so isolated, generally, because of the technological advances. You can sit home and make a record, you can search the world for information, you can talk to your friends, you can watch TV—you can do it from your bedroom. So you don’t tend to get out. But when you do it creates a space in you that would not have been created from your own technological experience at home. It gives you more tools. And those are the kinds of tools that are inspiring, and they are empowering—I mean, I hate to use some of these old words, but that’s exactly what it is. There’s nothing quite like getting out with friends and participating in the world, on a street level. I’m not talking about “sign the petition on, you know, Facebook” or something like that. It’s a visceral reality as opposed to a technological one. And it makes a difference. It makes people enthusiastic and it gives them strength and courage in their convictions.

I think that’s all part of the process of learning how to become not just involved but how to become important. To make your voice heard and to know that it counts for something. These are the themes that my father was writing about 80 years ago—that everybody counted, that there is something unique about everyone, that there are no throwaway people. We live in a world where we tend to think of ourselves as not having any real value; that one person can’t make a difference. And that’s a lie. You can make a difference. And you can make it even more so with a lot of friends. Not only that, you make more friends. That’s true, by the way, of all political stripes. There are people on the right, there are people on the left—they’re all out there yelling about one thing or another. This is good. They don’t have to be right. They have to be involved. And when you are involved, then you can evolve. And when you evolve, then we can reach consensus. But if you’re stagnant, if you can’t get out there and do anything, nothing happens. And that’s where we are, I think, at this moment.

AV: That’s what your dad was up to, wasn’t it?

Guthrie: Yeah. That was the idea. That everybody counts. Everybody has a voice. Learn to use it. Don’t be afraid of making any mistakes. And if we all get together and start learning how to be civil with each other—you know, you give the other guy a chance to say something, then he gives you a chance to say something. If you learn those kinds of tools, that’s what people in this Congress need to do. But you don’t learn that sitting at home where someone can leave you a message and you can answer it when you want. You don’t have to learn to be civil. It’s all at your leisure. That doesn’t work for everything. For some things, don’t get me wrong, it’s great. I love when the phone rings and I don’t have to answer it. I can get back and push the button. So there’s some value to that. But that’s not everything. There are times when you have to get out and deal with other people, other humans, in order to help the world, you know, move ahead and get through these times.

AV: What can folks expect at your show this time around?

Guthrie: I have no idea. My general philosophy is: no judgment, no expectations. I live by that rule, so it’s kind of hard for me to say what somebody should expect, except that, you know, I’ll be there.

AV: So your set list is not set in stone?

Guthrie: Generally the set lists are up for grabs at the beginning of any given tour and we’ll work it out so that it makes some sense and there’s some continuity, so you’re not just listening to some guy singing a bunch of songs without any thought…

This particular tour is one of the longer ones. It’s a two-year tour that started in July of 2012, and it goes all the way until December of 2014. It’s a two-year Woody Guthrie celebration, and it’s pretty much reached, I think, about the best that it can be at this point.

AV: Your son is playing with you?

Guthrie: Yeah, that’s what’s changed. The configuration on stage has changed. The songs tell a good story right now. Even if I didn’t say a word and just did the songs, the continuity is there. But what has changed is the guys who are playing with me. When I started the tour, for example, in July of 2012, I was with my entire family. All the kids, all the grandkids, 16 people on stage, and we had a wonderful time. From there it went to a solo tour that went from October 2012 until about May of 2013. And now we’re picking it up again with this configuration, which is my son Abe, my friend Terry [A La Berry] on the drums, and my neighbor Bobby Sweet, who’s a great guitar player. So it’s just the four of us on stage now. It does allow me to add something if I feel like it, or take something away if the show’s feeling a little long, or whatever. These guys have played with me for so long that we can really do anything. We don’t need to rehearse anything. We’ve done all the individual songs before, but we haven’t put them together quite this way.

AV: You know, the venue you’re playing in Buffalo used to be a church.

Guthrie: I didn’t know that.

AV: And the converted church in Alice’s Restaurant, can you talk a little about that?

Guthrie: We bought it a little over 20 years ago. I say ‘we’ because that was a community effort. That was me and, you know, hundreds of people who contributed a little bit to put a down payment on the thing. And we started two foundations that operate within the church that run hand-in-hand. One is an interfaith church foundation, which allows us to do all kinds of things that are uniquely church-oriented. For example, when we bought the building there were people nearby—you know, a lot of older folks—who had gone to church there when it was still a church. And they asked very politely: ‘Would you maintain some of the features of what it was?’ And I said, ‘Absolutely, the doors will be open to you, and you can come.’

These old buildings, they have histories. You know, we’re here for a short time. We are the custodians of not just what we think, but the history of the building itself. And after us there may be other people in there who do other things. Continuity is important to the community. So we do a lot of community work, and a lot of that has to do with the interfaith church foundation. And we have an educational foundation that runs the music programs and the art programs and the more educational part of what we do. Between the two, we can get a lot done. So there’s a lot of social services, and there’s a lot of involvement on the local level. Like free food, that kind of basic stuff. Especially these days, in any given town, there are a number of places that you can go to get something to eat on certain days. It might be the synagogue on Tuesday, a church of a different denomination on Thursday. No one can do it all and so they spread it out among the different facilities. So, we’re Wednesday! [laughs] Every Wednesday we have something to eat for everybody who walks in the door. We do fundraising events for things that are important to me, whether it’s Huntington’s disease...and we have walks and marathons and we have dinners, you know, all the usual stuff that you would find in any local community center. In addition to that because it has the history that it does, you know, with me, we do a lot of music all summer long. We just got some heat and air after 20 years! We haven’t put it in yet. We just finished raising the money for it. So now we’ll be able to use the entire building throughout most of the year so we can extend the services. I’m looking forward to that.

AV: The study of Huntington’s disease, which claimed your father’s life, what progress is being made on that front?

Guthrie: There’s been a lot of progress. You know, they don’t make progress in the study of one particular disease like people would imagine. They make progress because the whole world is doing research. The ways to treat or the ways to investigate what’s going on can come from anywhere. You don’t know. What’s happened is that a lot of these organizations—you see them all the time, this organization that does that and they raise money for this—everybody’s sort of separate on the ground level. But behind the scenes, the scientists and the geneticists and the doctors and the research people—they might be focused on one research area but they have value to everyone in other areas.

The hardest thing now is for these guys to find out what each other is doing. There’s a backlog of information. They may have discovered, already, how to fix something but that knowledge isn’t in the hands of the people working on that particular problem. We’re living in a world now where we’re making dramatic inroads into how things work. Now it has to be disseminated to people who are actually doing the work in some particular form. And that’s what’s going on. So one of the things that we do is that every year, we have a big dinner. And people with the disease and all their families can come. And they come. But they also come with doctors. Those doctors sit around with people who are, you know, dealing with this stuff—the families. We also have scientists. So they’re all sitting around the table. A lot of times, research scientists don’t actually meet anybody with the disease that they’re working on. It’s really nice to get them together and put faces on them. And they say, ‘I know a guy that’s working on this thing.’ This is where he’s at. So people get up and they talk about what they’re doing, and they all meet each other. Because eventually we’re all tied together anyhow. That’s one of the fun things we do at the church.”

AV: Which comes back to what you were saying earlier. “Get out from behind the computer.”

Guthrie: Yeah. It’s good for ya.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n41 (Week of Thursday, October 10) > The Son's Coming Up This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue