How To Stay Poor

by Bruce Fisher

Cuomo’s city groundbreaking, county’s city-killer moves

Meanwhile, back home, away from the threat of a self-inflicted economic Armageddon that suburban Congressman Christopher Collins and his fellow Republicans like the sound of, we enjoy an eerie continuity—featuring a governor breaking ground on the new city campus of the medical school, a county executive releasing his status-quo budget, and a mayoral race between a Republican challenger and a Democratic incumbent that is about as competitive as the contest between Bambi and Godzilla. It is as if we have no national government at all.

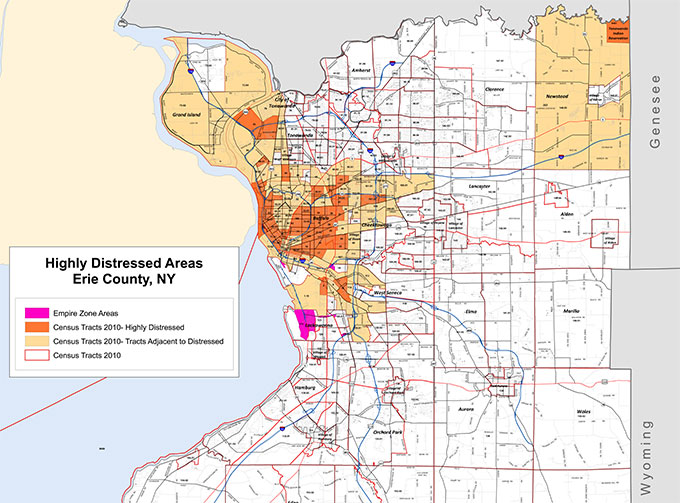

But of course, we do. And the best evidence of the utter failure of our national government can be read in the map that the Erie County Industrial Development Agency publishes on its web page under the button “Highly Distressed Area Map.”

This map shows where the highly-distressed Census Tracts are. Buffalo natives know this geography by heart: The poorest areas here are west of Richmond Avenue and Elmwood Avenue to the Niagara River, and east of Main Street and south of Delevan Avenue to the Buffalo River. Close-in to the city, pockets of deep distress exist in Cheektowaga and Tonawanda, and on the south bank of the Buffalo River, too. The census tracts adjacent to the areas of persistent low incomes, unemployment, substandard housing, and childhood poverty comprise all of the City of Buffalo, most of Grand Island, Kenmore, Cheektowaga, much of West Seneca, but no part of either Amherst nor Hamburg—the two townships where two of the three campuses of Erie Community College are sited.

That’s the picture: economic distress that’s not hard to find on a map if one uses data from the federal government, but a local-government policy that isolates the thing that is supposed to alleviate poverty from the places where poverty persists. Two of the three campuses of Erie Community College are located not in a highly distressed area, nor in census tracts adjacent to the highly distressed area, but only in areas that are not even next to the areas next to the highly distressed area.

Persistent poverty. By design.

Gerald Grant’s recent Hope and Despair in the American City: Why There are no Bad Schools in Raleigh is one of the best accounts of how a “conservative” majority on the United States Supreme Court skewed the school-desegregation process away from metropolitan-wide solutions to municipality-by-municipality rules. Since the 1974 Milliken v. Bradley decision, all the cities of the Rust Belt have come to have Highly Distressed Census Tracts maps that are exactly like Buffalo’s. Poor people got locked inside old municipal boundaries.

And the expense of keeping poor people isolated grows and grows—with local governments, and local school districts, maintaining the status quo no matter how many times a governor comes to town to add a new urban economic input. In the new Erie County budget, for example, the County Executive (like most of his predecessors) happily announces aid for cultural institutions that are located mostly inside the urban core, but follow the money: the proposed budget announces $68,000 in new spending for culturals, $5 million for new spending at the Erie Community College’s suburban campus, but boldly asserts that the budget recommends “tens of millions of dollars of infrastructure improvements on roads and bridges throughout Erie County” without mentioning that all of that money will be spent outside the city.

It is the way, as they say, of their people.

Underinvestment undergirds underperformance

Urban poverty has been a feature of the American landscape since the great suburban migration began in earnest after World War II. Urban poverty has been the target of every kind of policy initiative that American policy intellectuals have been able to imagine—except, of course, the kind of policy initiatives that actually work. The new consensus of the new urbanists is that a taste-based re-migration, consisting principally of what were once called “symbolic analysts” by Robert Reich and are now called the “creative class” by Richard Florida, will remake urban centers, and that the agglomeration of all this talent will be the economic salvation of all—including the persistently poor.

Really?

Quibblers are starting to get bold enough to step forward and ask whether gentrification alone can break up the problems that William Julius Wilson described in his air-clearing 1997 study When Work Disappears. We all love place-making, and mixed-use developments, and transit-oriented development, and density. But what about public schools 80 percent of whose students come from households whose incomes are below the poverty level? Do the new “green” zoning codes make room for places where people with children might possibly earn wages that are high enough to lift their children out of poverty? Or are the persistently poor supposed to leap past minimum-wage jobs, past non-existent union-scale manufacturing jobs, past even the shrinking supply of civil-service jobs, and go directly into high-paying jobs as symbolic analysts in the Creative Class?

What is clear, and recently re-calculated, is that breaking people out of persistent poverty is a massively expensive undertaking—almost as expensive as putting Erie County’s proposed “tens of millions of dollars” into suburban infrastructure year after year after year.

As my student Ryan Keem recently showed in his econometric analysis of test-score performance in every single school building in Erie County, the correlation between low household income and low performance on standardized tests is the same now as it was when the desegregation movement got underway in earnest in the 1960s. The key correlation is not between the race of the student and the score on the test, but between how much money comes home where the test-taking student lives, and how that student performs on test day.

And what we know about increasing household income is this: Governor Cuomo has it right, and Erie County has it wrong. You increase household income in areas of persistent poverty by stepping up the public inputs where the poor people are—in Cuomo’s case, by investing in educational infrastructure that will also employ some people from the immediate area—as Cuomo committed to when he broke ground on the new UB medical school this past week.

Meanwhile, Erie County government’s budget features more of the Rehnquist Supreme Court’s recipe: huge investment in the suburbs, tiny investment in the city, and a skewed investment of education and workforce-training dollars into the suburbs, far, far from where the poverty is.

When the likely Republican challenger to the Democratic incumbent County Executive steps forward in 2015, we will face a curious replay of 1999. If Erie County Clerk Chris Jacobs runs, it will be a city-centric proponent of education challenging a suburb-focused proponent of suburban roads, suburban community colleges, and suburban sprawl. Jacobs, having created a charity that offers private and parochial schooling to poor kids lucky enough to have some family member willing and able to invest in them, is part of a philanthropic tradition—the old- fashioned charity focused on the ‘deserving’ poor. Even some union teachers quietly applaud him, because Jacobs’s Buffalo Inner-city Scholarship Opportunity Network (BISON) fund is focused on the proposition that city school teachers know is true: that poverty is hard to break, and that it takes more than a classroom to break through to kids oppressed by the lack of job opportunity, the lack of job-training, and the overall lack of income afflicting their nuclear and extended families too. Teachers know best: the supports just aren’t there the way they need to be for poor kids.

Money matters: where the poverty is worst, the investment has to be stepped up. M & T Bank president Robert Wilmers has invested millions in a single elementary school in a zone of persistent economic distress, right there in the center of the ECIDA map. The outcome? Surprisingly good—after extraordinary effort, money, and assistance. Ryna Keem’s numbers show that with all of that, you can begin, just begin, to get to the results that a high household-income school routinely gets from its high household-income students. As for the city schools without that help? The same here as in Rochester, Syracuse, Albany, Cleveland, everywhere else the poor are concentrated: low scores, low graduation rates, persistent poverty replicating itself year after year, class after class.

Undermining urban prospects is, in economic terms, a stupid, stupidly expensive policy. With the new enthusiasm for cities, it is also stupid politics—except in the Confederate States. The fashion for Republican politics of the Tea Party or Spaulding Lake variety will, one hopes, have been killed by Congressional behavior this month. But the intellectual consensus about urbanism, and the economic consensus about urban-focused investment, may yet be a vehicle for a consensus urbanist politics that may even make room for a Republican who bold enough to say that the Highly Distressed Area Map won’t change until the local-government policy picture changes.

Bruce Fisher is director of the the Center for Economic and Policy Studies at Buffalo State College. His recent book, Borderland: Essays from the US-Canada Divide, is available at bookstores or at www.sunypress.edu.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n42 (Week of Thursday, October 17) > How To Stay Poor This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue