Trust Nothing But Your Own Strong Voice

by Patricia Pendleton

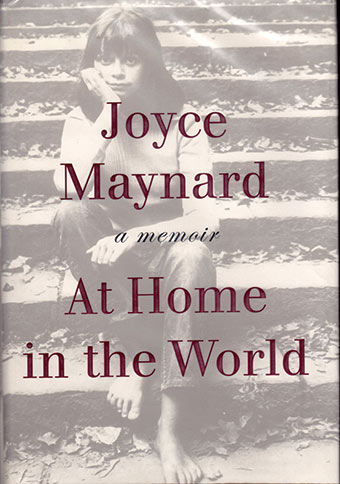

At Home in The World: A Memoir

by Joyce Maynard

Picador USA, St. Martin’s Press, 1998

Why review a book that was published 25 years ago? Author J. D. Salinger dropped out of the publishing world after the success of his cult classic novels, The Catcher in the Rye and Nine Stories. Joyce Maynard’s memoir is a coming-of-age story about a precocious girl and a famous man who were both icons of the 1970s during the time of their one-year relationship. Her personal investigation and insights are relevant today as Salinger is now the subject of a new biography and documentary film.

“Trust nothing but your own strong voice” was the message he imparted to the young writer, Joyce Maynard, 40 years ago. She published her first memoir in 1973 at age 19, one of the youngest girls to ever publish a book (following Francoise Sagan and Ann Frank). After a successful writing career, a marriage, and three children, she was ready to open up about the story she had kept quiet about—her connection to the reclusive author that began when she was just 18, the same age as her own daughter when she began this memoir project.She was able to find the material to spark her memories from letters, a huge collection of letters—not only those from Salinger. Her mother was a letter writer—so was her sister, Rona. Maynard also sent detailed reports to both women. Most of this writing had been saved.

Fredelle Maynard, was an ambitious, bright woman who found frustration when she went out into the world in 1948 with a PhD from Radcliffe. She was eager to find a position as a professor, but was told to stay home and have babies. And so she did. Her painter husband took a position at University of New Hamphire to support the family while she built dollhouses, sewed, baked, and published articles about domestic life in women’s magazines. She later published Guiding Your Child to a Creative Life, a subject she knew well. Joyce Maynard inherited her mother’s ambitions, but later admitted that she never planned on becoming a writer—it was just something her parents taught her how to do when they coached her to enter and win children’s essay contests during living room sessions over tea and cookies. Her professional writing career began at age 15 when she was paid $100 for an article in Seventeen magazine.

She went off to Yale in the fall of 1971, but her freshman year was consumed by commercial writing assignments. Seventeen sent her out to interview Julie Nixon Eisenhower and report on the Miss Teenage America pageant. Unhappy about the way they edited her pageant article, she contacted the editor of the New York Times to complain—something only a talented young writer could gain any attention for. This contact resulted in an invitation to write a piece about growing up in the 1960s. Maynard received $750 for her 3500-word article and the story was featured on the cover of the New York Times Magazine in the spring of 1972—complete an impish photo of her as a typical teenage girl. The article presented a world-weary and alienated point-of-view of youth that struck a chord with readers. She received a wave of mail in response, including one letter that changed her life. He knew exactly what this early publishing success could do to Maynard. Salinger wrote her sage advice warning her of the dangers of the reader’s voice in her ear as she wrote.

This was the start of a correspondence, mentorship, and romance that consumed the following year of her life. That year marked the initiation of the Equal Rights Amendment and the elimination of the military draft. The first Women’s Studies courses were introduced at Yale and Ms. magazine was launched. George McGovern was seeking the Democratic nomination a a scandal was sparked when burglars broke into the executive offices of the Democratic National Convention at the Watergate Hotel. The sexual revolution was in full swing. Campus pairings of older male teachers with young female students were viewed as romantic rather than disturbing. Mia Farrow was married to Frank Sinatra. Nobody was talking about sexual exploitation or harassment. Maynard began to take herself seriously as a writer through the encouragement she received from “Jerry.” The fact that he was 35 years older was of little consequence—even her parents were accepting of this liaison. Salinger revealed himself to her in letters and nightly phone calls. He quickly pointed out to her that they were each half Jewish and from New Hampshire—kindred spirits. “We are landsmen,” he told her. She had more to say about The Dick Van Dyke Show than Thomas Pynchon. He liked her lack of interest in the literary world he had disdain for—the artiness in writing. “The tweedy types sucking on cigars and sensitive women in black turtlenecks” were evidence of the kind of “writerliness” he had run away from. Although, Salinger was the toast of New York while in his 30s, he had no taste for the celebrity that came with becoming a best-selling author. He traded that in for quiet and solitude of New England. “Publication is a messy business,” he told her and reminded her that the life of a writer is anything but fun. She was fascinated by the way he spoke to her and all his quirky ways.

The summer after her freshman year, Maynard landed an editor job and house-sitting gig in New York. While other students were working at fast food joints or unpaid internships, she was living the big city life. Where else could she walk past John Lennon and his son, but in Central Park? Salinger drove his BMW into the city on weekends to take her back to his home in Cornish. The relationship separated her from any kind of city lifestyle of socializing with her peers. The successful Times article led to a book contract. Dover asked her the article into a memoir, Looking Back: A Chronicle of Growing Up Old in the Sixties. Salinger convinced her to give up the New York summer to finish out the season at his home in the country to get serious about writing her book. She agreed and made the move up to his place—began sharing his regimented daily life. They arose early each morning just as her father had taught her to do as a child. They ate warmed frozen peas for breakfast. He spent hours in his study meditating and writing while she too worked on her writing projects. Salinger was a practitioner of Vedanta Hindu spirituality and homeopathic medicine. He maintained a strict diet of raw foods that Maynard adopted—not the best thing for a young woman with anorexic tendencies.

Maynard reluctantly returned to student life in New Haven that fall. She fixed up an apartment retreat for herself, but none of it felt right. After just days, Maynard turned her back on Yale to return to Salinger’s home. He encouraged her to write about what she knew with originality, tenderness, and love. One morning, he mentioned a dream from the night before about the two of them having a baby named “Bint.” Already thinking about motherhood, Maynard assumed that they would spend the rest of their lives together. This is how 18-year-old girls think. Salinger was in awe of her unpretentious ways and appeared to be her biggest fan. He offered complete acceptance—for awhile, anyway. Gradually, criticism crept in—about her messiness, cooking, and clothing. He chastised her for a published piece about her parents that he considered a total fiction. They had given her the ability to think and write, but they were frustrated creatives who were overly demanding at times. Her father’s painting career had been thwarted by his job and drinking. Maynard could not even bring herself to talk to her mother about her father’s drinking—much less, write about it honestly.

Salinger’s disappoint with her was complete when she leaked his phone number and precious privacy to Time magazine and they called him to request a commentary from him on her upcoming book. Maynard did not see it coming when he explained to her the fundamental difference between them. “You love the marvelous, exciting things the world has to offer—I’m holding you back. You’re not ready for this.” He had to finally put an end to the charade that they were going to have a baby together. Salinger sent her away broken-hearted with two 50-dollar bills just before her memoir was published. In Salinger’s view, the book represented everything he told her not to do and everything he despised—the quality of “newsstandland” over true thoughtfulness.

Maynard continued writing articles and began to grow up. Like her mother, she married a painter and embraced motherhood. She too wrote for women’s magazines and received acclaim for her well-known New York Times “Hers” column. Salinger was out of her life, but she continued to seek his approval. When she sent him a copy of her first novel, Baby Love, he called her with a response. “I’m sickened and disgusted. The book is piece of junk.” She adapted two novels into screenplays (To Die For and Where Love Goes) and continues to earn a good living as a writer. She moved on. It was not until she was in her 40s and living far away in northern California after a divorce that she began to reread the Salinger letters and revisit this chapter of her early life. Maynard discovered that she had been just one of many young women that he seduced through letters. One of these other women articulated what took place: “It wasn’t sexual power, it was mental power. You felt he had the power to imprison someone mentally.” Maynard learned that Colleen, the au pair who Salinger had been corresponding with just before he wrote her that first letter, eventually returned to him until he died in 2010.

In search of closure as she was working on this book, Maynard wrote him several letters. Upon receiving no reply, she finally drove to Salinger’s home to confront him personally. He was 78 when she asked “What was my purpose in your life?” He was clearly angry and offered her no kindness—chastised her once again. “You don’t deserve an answer to that question, Joyce. You have spent your career writing gossip—empty, meaningless, offensive, putrid gossip. You live your life as a pathetic, parasitic gossip. The problem with you, Joyce, is that you love the world. I knew you would amount to this—nothing.” The man was self-absorbed and likely suffered from deeper issues. He was unable to see that Joyce Maynard did find her own strong voice and she actually attributes her readers for their huge influence in shaping her writing. The book opens with a quote from The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams: “Real isn’t how you’re made,” said the Skin Horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.” J. D. Salinger was a difficult person to love, but Joyce Maynard did it—she made him real.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n46 (Week of Thursday, November 14) > Trust Nothing But Your Own Strong Voice This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue