Next story: Round 1, Week 1: Fountainhead vs. The Observers

Gary L. Wolfe Puts Faces on Homelessness at Artspace Buffalo Gallery

by Patricia Pendleton

There's No Place Like Home

During the early 1980s, great numbers of people without homes inhabited the streets around my neighborhood in the East Village of New York. My sister visited from the sheltered world of suburban Buffalo. When we had to step over a man lying on my doorstep one morning, she asked, “Shouldn’t we do something?” I brushed off her question with the laugh of a hardened city-dweller.

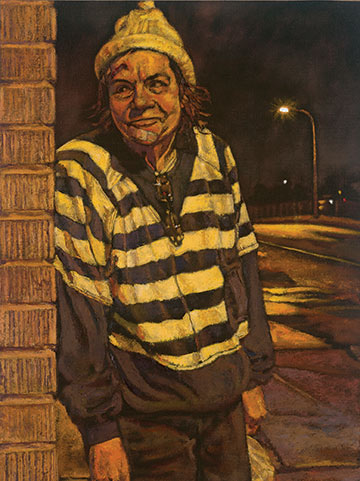

Still, all these years later, her concerned question remains relevant. Shouldn’t we do something? Why does homelessness persist? Gary L. Wolfe’s exhibit Out of Darkness aims to raise public awareness of this issue during a holiday season of colder days, long, dark nights, and social festivities inside the warmth of home. Wolfe’s exhibition at Artspace Buffalo Gallery features more than 25 portraits of individuals who have been homeless. Each piece includes a statement in the response to the question: “What is one thing that you would tell the rest of us who have not been homeless if you had the opportunity?” The oil paintings are crafted on black tarpaper, the standard construction material used on rooftops, both a metaphor for shelter and an ideal surface for capturing the light and texture of the gritty layered narratives unique to each person.

The show also includes an interactive installation that is a collaboration between the artist and two men who had experienced chronic homelessness. The Wall of Forgotten Faces is a homeless camp with a makeshift bed on surface of stones, turned-over plastic buckets for seating, a transistor radio leaning against a large trash bag, and a wall of wooden shingles with faces peering through. Viewers are invited to write messages on sticky notes and add them to the wall. Inside the safety of an art gallery, the public sentiment is supportive and implies a wish to help. Outside on the street, we may be more likely to view the homeless as “other,” but this project asks us to see the face instead. An ancient Zen koan asks “What face did you have before your parents were born?” Looking at the portraits seems to answer this question—each suggests a glimpse of humanity apart from cultural roles. As the accompanying commentary is read, we discover the face of homelessness is often ordinary folks who once had homes and jobs and people to count on—until circumstances changed. The artist has created an exhibition catalog of essays and images of the paintings. He reminds us that we do not have to be homeless to understand it—we know its opposite. Those of us with adequate housing shudder to imagine being without.

Seventy years ago, the humanist psychologist Abraham Maslow introduced his “Hierarchy of Needs” concept to explain the specific requirements necessary for optimum human potential. This pyramid of needs lists at the bottom our physical requirement for food, water, and sleep above all else. Safety and security follow those. The next higher level is love, friendship, and intimacy. When all the basics are covered, a person might entertain loftier notions at the top of the pyramid, such as personal esteem and accomplishment. We do not find the words shelter or housing on this list, but beyond food and water, there is little sleep, safety, or security without four walls and a roof. Most creatures fashion nests and dwellings of one sort or another—a place to return to for privacy, warmth, and comfort. My dictionary features a four-inch long bit of text to define the word “home.” Spiritual traditions often equate it with an internal ground zero. The author Maya Angelou wrote that “the ache for home lives in all of us. The safe place where we can go as we are and not be questioned.”

While some without housing require extra support due to mental illness and addictions, the primary cause is poverty and lack of sufficient affordable housing. The 2013 guidelines indicate that one person living with less than $11,490 a year is living in poverty. That number is $15,510 for a couple and $23,550 for a family of four. Buffalo lands on all the most-impoverished lists that are posted regularly in the media. Most alarming is that 57 percent of the children under age five in Buffalo are living in households with incomes under the poverty guidelines. One study claims that 58 percent of Buffalo renters pay 30 percent (or more) of their income on housing. Unfortunately, many landlords continue to assess applicants with the outdated formula requiring rent to account for no more than 25 percent of income. Credit checks are standard and two months of rent are increasingly necessary to a secure a lease. Qualifying for housing is tough even for those willing to fork out 50 percent of their pay for shelter. People working minimum wage jobs ($7.25 per hour in New York State) tend to have no margin for error. A necessary car repair means not enough funds to cover the rent, and giving up the car means giving up the job. A January utility bill adds another setback. Borrowing from Peter to pay Paul simply delays the inevitable catastrophe—catching up is impossible. The fall from grace is short.

Consider what a bold change might look like. The idea of “Basic Income Guarantee” has been in the news recently as a small wealthy country, Switzerland, is close to initiating a plan to pay each citizen a monthly wage comparable to about half the average per capita income. This plan places no restriction on an individual’s ability or desire to work—everybody receives it. The grand experiment to immediately eliminate poverty is gaining support in our country, but the 35 percent flat tax will be a hard sell. Providing a baseline standard of survival pushes back the need for most government benefits and the accompanying stigma for those who receive them. Employment (even minimum wage work) is instantly converted to a means of getting ahead. Imagine how uplifted people might feel to have a possibility for self-efficacy. If this plan was a board game, we would all go immediately to the top of Maslow’s needs pyramid.

“Being homeless makes you like the sand on a beach—each wave that washes over you—every change in the weather, every unwelcome animal, every intrusive person—takes a bit of you when it recedes.” This is the reflection of a man named Peter who lived under a bridge for five years before finding the refuge of residence in the Matt Urban Hope Center’s Housing First program. Wolfe’s paintings, installation, and catalog offer a chance to ponder those who find a way out of the homeless dilemma thanks to organizations such as the MUHC and various local churches who have supported this project and give much-needed help to homeless individuals in Buffalo.

Artspace is located on Main Street in a rehabbed historic downtown building where affordable housing is available for artists. Nake a visit to Gary Wolfe’s thought-provoking show that will remain on view through December. Call 430-0629 for gallery hours.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n49 (Week of Thursday, December 5) > Art Scene > Gary L. Wolfe Puts Faces on Homelessness at Artspace Buffalo Gallery This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue