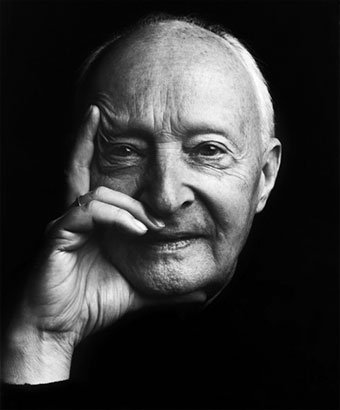

Lutoslawski at 100

by Jan Jezioro

Celebrating the centenary of the 20th century’s greatest Polish composer

Witold Lutosławski was born in Warsaw on January 25, 1913, and numerous major orchestras worldwide are celebrating the event by scheduling performances of one or more of the composer’s late masterpieces. While such major orchestras as the Berlin Philharmonic, the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, the Mexico National Symphony Orchestra, and the Chicago Symphony are marking the occasion by programming Lutosławski’s challenging Concerto for Cello and Orchestra (Koncert wiolonczelowy), the honor of offering what will be the first-ever Buffalo performance of the 1970 work falls to the University at Buffalo Symphony Orchestra, under the baton of its innovative music director, Daniel Bassin.

Some years back, Phil Rehard, concert manager of Slee Hall, inaugurated what has become a very popular “Brown Bag” musical series on the first Tuesday of each month during the academic year. This lunchtime series features both students and faculty in performances of selections from a wide-range of classical music works, and at the concert a couple of weeks ago, Bassin programmed an entire concert of works by Lutosławski. The last piece on that program featured UB graduate student T. J. Borden, who will be the soloist on Friday March 1 at 7:30pm in Slee Hall, when the UB Symphony program features the Lutosławski Concerto for Cello and Orchestra. If the finely finished, yet emotionally involved manner in which Borden performed the lengthy solo opening section of Lutosławski’s concerto at that event is any indication of his mastery of the entire work, the concert is not to be missed.

Lutosławski’s mother was a physician and his father a talented amateur musician, while his uncle was one of Poland’s most eminent philosophers. Growing up in an artistically and intellectually stimulating atmosphere, Lutosławski played the piano well by the age of six and began composing on his own by the age of nine, then went on to study composition under a former student of Rimsky-Korsakov, while developing into an excellent pianist. His 1938 Variations for Orchestra gained him recognition in the Polish musical world before his career was interrupted by service in the army followed by incarceration in a German prisoner of war camp. After his release, Lutosławski survived the brutal Nazi occupation of his country by giving two-piano concerts, most of them underground, with his fellow composer Andrzej Panufnik, who later went on to his own distinguished career. One of the very few of his many compositions to survive from this desperate era is his virtuoso work for two-pianos, the Variations on a Theme of Paganini, which local music lovers got to enjoy last month at a BPO concert as an encore by the twin sister pianists Christina and Michelle Naughton.

In the post-war period, Lutosławski fell afoul of the Communist government, when his Symphony No. 1 became the first musical work to be banned in Poland, forcing him to make a living arranging folk music and writing for radio and film. The artistic situation in Poland improved somewhat after the death of the Soviet dictator Stalin in 1953, and returning to the composition of abstract music, Lutosławski scored a worldwide success with his brilliant Concerto for Orchestra of 1954, one of only three works by the composer to be performed by the BPO, most recently in 2010 under JoAnn Falletta.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Lutosławski’s international reputation continued to grow, and he was much in demand as a teacher and a conductor, making the first of his many visits to the US in 1962. Meanwhile, his compositional style constantly evolved, a chance hearing of a broadcast of John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra sparking his interest in aleatoric music, in which elements of unpredictability or chance play an important role. In adopting this new compositional approach, Lutosławski followed his own path, avoiding the potential excesses of too free a reliance on the method. As he observed, “In my composition the composer still remains the leading factor, and the introduction of the chance element in a strictly fixed range is merely a way of proceeding and not an end in itself.”

The renowned Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich had asked Lutosławski for a cello concerto for many years and when the English Royal Philharmonic Society offered a commission to the composer he used to opportunity to write one. Rostropovich told him not to worry about possible technique problems, as he would just figure out how to play whatever he was given. Rostropovich later remarked that he “had to devise some fingerings that were utterly new to him even after thirty years of performing in public.” Rostropovich’s strong and continuing advocacy of Lutosławski’s powerful cello concerto, a work that many consider to be the composer’s masterpiece, ultimately helped to gain it a spot in the repertory of most major cellists.

Admission is free. Information: 645-2921; www.slee.buffalo.edu.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n8 (Week of Thursday, February 21) > Lutoslawski at 100 This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue