Next story: Book Review - Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief, by Lawrence Wright

Book Review - Theo, by Ed Taylor

by Patricia Pendleton

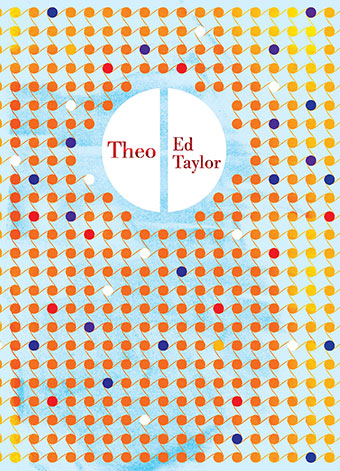

Theo

by Ed Taylor

Old Street Publishing Ltd. 2014

Find this attractive new publication tucked into the Local Authors shelf at Talking Leaves Books. “Theo” was published in the UK earlier this year, but many of us have been awaiting the launch of Ed Taylor’s debut novel in our community. Taylor is a Professor of Literature at Buffalo State College, a published poet and short fiction writer, as well as the former executive director of Just Buffalo Literary Center. This is not a story set in Buffalo. Theo’s world is populated with the freewheeling associates of a legendary British rock star during the 1980s. They are stationed at a high-rent beach house on Long Island awaiting the celebrity’s return for a recording session. The reader is given an intimate look into the observations and sensations of the performer’s ten year old son, Theo, the only child among a motley crew of narcissistic music world adults. Narrated in the third person, the tale has the feel of a memoir as the boy puzzles over their behavior and awakens to his own individuality. The coming-of-age story touches the dark side of an era colored by the culture of a downtown Manhattan arty club scene. It is a time when important news arrives on a fax machine, a decade before technology entered the personal arena.

The author includes gems of fictive truth to add authenticity to the time and place. A female house guest tells the boy that she met his mother, Frieda, at the Mudd Club. The notable underground venue opened in 1978 for brief five-year stint on White Street. Someone turns up wearing a Bush Tetras t-shirt, the edgy 1980s girl band little known outside of lower Manhattan. Theo has a rich imaginative world that provides resources to survive through the formation of his curious youthful mind. A paid minder named Colin casually looks after him, while also keeping an eye on the boy’s paternal grandfather, a pipe-smoking, rum-drinking Brit named Gus. Gus and Colin offer Theo the stability lacking from the parents. Theo worries about his them. He learns that Frieda met Adrian at a club where she was known to be a “good connector,” the kind of woman who promotes bands and artists on the rise. She “collected people like pets...that was her art.” An addict who cycles in and out of rehab, Theo detects a certain smell on Frieda when she is “sick.” Adrian hired the minder after Frieda crashed the car with Theo in the passenger seat. She tells Theo that “the end of pleasure is pain.”

The adults drop complex ideas into conversations with Theo, ideas that he later ponders. Mingus parades about in costumes and explains art to Theo. Being an artist is about ideas rather than pictures. “Some get rich off it, some get killed by it.” Adrian does not tell Theo to follow him into the music business. “He says music either grabs you by the throat or it doesn’t. And if it leaves you alone you’re lucky.” That could be said of all the arts. The pursuit is risky—don’t go there if you are not compelled. The adored Adrian returns to the house after a long concert tour and greets his people with a pile of gifts under the lights of an off-season Christmas tree, staged to impress. Theo is given yet another Japanese robot from one of his father’s friends, but he is not an ungrateful spoiled kid. He is simply accustomed to disappointment and has learned to politely accept what he does not want. All he really wants is time with his father and a proper meal. Theo wants only to show off to his Dad the butterflies in his room, but his attempts fall flat every time. He fondly recalls tiny paper pills from Japan that transformed into dragons and swans when dropped into water, an earlier gift from Adrian. He wants more of that magic again. “Dad Dad Dad,” he pleads. “Can we please do something.” The familiar parent child scenario is cut short with another version of later. Adrian just wants to escape from the pressures of his demanding work schedule.

If Theo’s story was lyrics to a song, the refrain would be “I’m hungry.” The boy is continually overlooked in the nurturing department--most evident is the lack of regular meals. Frequent references to Fray Bentos come up when he asks about something to eat. It turns out that this canned steak and kidney pie is a popular staple in the UK and one of the only food items regularly stocked in the kitchen. The boy knows about things he should not. The nudity and over-sexualized atmosphere stirs confusion and new feelings. He considers death and morality. He questions “Why do pictures of the devil always show him smiling, if he is supposed to be bad. Pictures of Jesus never show him smiling, and he is supposed to be good.” There are frequent references to the idea of life as a process of moving toward something. Taylor favors short sentences broken only by periods and commas, a minimalist style that keeps the pages turning and reinforces moving toward life along with Theo. The narrator explains the weightiness of the boy’s dilemma. “Theo feels like he’s carrying something heavy all the time and he’s not strong enough, he needs to be older, bigger, for what they give him, the adults.” His liberal parents intentionally treat him like an adult who is free to make decisions. They allow him to stop attending school simply because he said he did not want to go. He craves supervision and criticizes Colin and Frieda for their willingness to leave him with other adults who tend to ignore him. “They’re like lifeguards who talk to girls instead of watch swimmers.”

A lot happens to Theo during the days tracked in the book. While much of this is disturbing, his ability to cope is affirming and there is a brightening surprise at the end. Theo inspires caring. The name, Theo, means God. The boy almost lives up to this in his display of Zen-like qualities. He wonders about future work options and concludes that he might be good as a waiter, as that is all he ever does among the adults, a practice in patience. Each of the four chapters begins with a poem or quote. One by Tim O’Brien, Vietnam Veteran and author of The Things They Carried, captures the essence of Theo’s experience: “What sticks to memory, often, are those odd little fragments that have no beginning and no end.” We are shown an inside view of those fragments that will shape Theo into a man. I am left hopeful that the seeds of his challenging life will sprout into wisdom. He may even become a writer. The story arrives from the view of a ten year old, but it is an adult story. A line from the well-written book sums it up: “Like Faulkner said, the past is never dead, it’s not even past. We’re still in it right now.”

blog comments powered by Disqus

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v13n23 (Summer Guide, Week of Thursday, June 5) > Summer Guide: Summer Reads > Book Review - Theo, by Ed Taylor This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue