Book Review - Little Failure: A Memoir

by Aidan Quinn

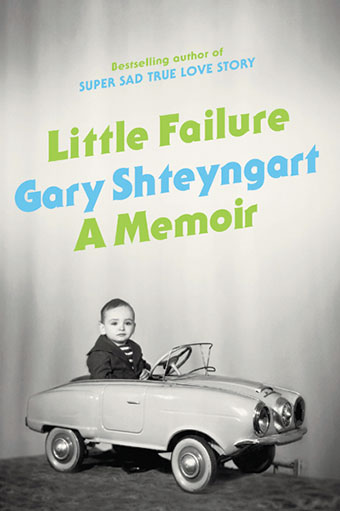

Little Failure: A Memoir

by Gary Shteyngart

Random House, January 2014

Meet The Shteyn

“On most days,” Gary Shteyngart muses in his new memoir, Little Failure, “I have my head so far up my family’s ass I can taste yesterday’s borscht.” The elder Shteyngarts have reservations about their son examining the familial colon, snapping pics with his Google Glass. “Just don’t write like a self-hating Jew,” his father tells him. But readers—whether savvy to the Shteyn or longtime poseurs and would-be initiates hoping to allay the insecurity they feel while nodding, gently aerating their Chardonnay, and pretending to have read The Russian Debutante’s Handbook, Absurdistan, or Super Sad True Love Story during chit-chat at all the right parties—will find out that this isn’t such an unsavory prospect, after all. Shteyngart takes this lower-intestinal beet-based multisensory memory stew and distills it into a provoking, illuminating, and laugh-out-loud trip through the life of an immigrant, an author, a neurotic, and—of course—a failure.

Most who approach Little Failure will be familiar with Shteyngart’s novels. Finding some of the same characters and scenarios in both the novels and the memoir (most notably a botched circumcision) readers will see that the author has fictionalized both the themes and the gritty details of his life with more unabashed abandon than anyone since F. Scott Fitzgerald. And then there are entirely surprising moments, never before fictionalized, which allow us to look upon some of the raw forces that formed the freshest satirist of the young 21st century.

But this does not number among the memoirs written by authors exclusively for their fan clubs. For those who don’t already know: Gary is “a calculating, attention-seeking mammal of few equals,” who looks “like a hunchbacked Jewish goat with a row of teeth like the Sarajevan skyline after the war,” frequently amazing his friends with his “intolerance, mean-spiritedness, and selfishness.”

Shteyngart has the uncommon ability of simultaneously satirizing his world and himself, and this is reason enough for even a reader who has never heard of the author to pick up Little Failure. Structurally at least it is the story of a Russian Jew who was born in 1972 in Leningrad; who penned his first work, one of the premiere examples of late-Soviet magical-realist propaganda, Lenin and His Magical Goose, at the age of five; who emigrated to the US in 1979; and who by 1988 found himself working the phones for the George Bush Sr. presidential campaign, “whispering to suburban housewives about the twin evils of taxes and Soviets.” “I would never second-guess the Gipper,” he tells one such housewife. “But when it comes to Russians, believe me, they’re animals. I should know.”

The narrative takes him to Oberlin College, in Ohio, in 1991. “Thank you, Oberlin College,” he writes. “Without your extended welcome to the weird, without your acceptance of the not yet fully baked, without the fathomless angst you impose upon all those who walk under your Memorial Arch, the angst that leads to the hapless intercourse your students have been waiting for throughout their miserable teenage existences, without these things it is conceivable that I would not have ravaged a woman with my Pentagon-shaped Soviet tusks until my thirties.”

The 30s are troublesome enough for Shteyngart already. His alcoholism, dating back to Stuyvesant High School, worsens, his misanthropy swells, he indulges a potential psychopath’s bigamist tendencies, and his job as a senior grant writer is gin-soaked and largely unfulfilling. (“I’d lie there on top of my office desk at 2:00 p.m., letting out proud Hibernian cabbage farts, my mind dazed with high romantic feeling,” he recalls.)

Notably, Little Failure departs from the uniformity of much memoir, in part because the memoir, I hope it isn’t trite to say, has no pretensions to autobiography. Shteyngart isn’t telling his own life story: He’s chosen to explain himself as an immigrant, as a writer, and as a son, spiraling back into his family’s past as he marches forward into his own present day. When he moves into more challenging memories he works through impressions and abundant rhetorical (or perhaps merely structural) questions; the result is not The Life, finished and polished, but a magnificent and likely ongoing effort.

This means that the picture is sometimes incomplete. Important figures appear, for whatever reason, like silhouettes. Paulie, a lecherous employer, father-figure, and would-be pederast, serves as a striking illustration of Shteyngart’s need to be loved—and of what he’ll ignore in order to get that love. But the man himself is a sort of stock goblin with but one known motive (to “pork” Shteyngart), given only two dimensions and two pages to breathe. Shteyngart uses no fewer than four glib footnotes to aid in obscuring Paulie’s identity. Usually I wouldn’t begrudge Shteyngart a humorous aside, no matter how trifling—but the glib is often the liminal, and here he stands guilty.

The reader will be even more frustrated with Shteyngart’s girlfriend (and later wife). He peppers the pages with a few details about his beloved—she is “an interesting one,” she has “real estate acumen,” she reads more than he does but does not physically abuse him. Unfortunately the details do not add up to a personality. Shteyngart even tells us that she comes from “a certain Asian culture,” almost as if he is too jealous of his wife to share her with his readers. In fact, we are told almost by accident that “the girlfriend” became “the wife” without ever having seen a marriage. She seems little more than a random selection from the long line of “warm and attractive women” who were “keen to walk down the street with me, hand in hand,” after the author sold his first novel.

Perhaps it is because Shteyngart—a guarded writer under his media-friendly wisecracking exterior (do check out the book “trailer” featuring Rashida Jones, James Franco, and Jonathan Franzen)—does not yet know what to say on the subject of his beloved. And in a memoir, that’s okay.

In fact, Shteyngart might not have himself figured out. The character he offers up—a boy who prepubescently pens a parody of the Torah, who holds a model plane aloft for eight hours in a “game” of transatlantic flight, who will later read in his high school yearbook, “Good luck, Gary. You’ll need it.”—is compelling, puzzling, delightfully weird. But one gets the impression toward the final pages that Shteyngart doesn’t know what to make of this character any more than he knows what to make of the shibboleth Ve’imru, Amen that ends the book.

This can be unsatisfying. But it isn’t a disappointment, and it certainly isn’t a failure. In fact, it’s tenacious.

“When you’re twenty-one there really is only one subject,” Shteyngart writes, discussing his first novel, The Russian Debutante’s Handbook. “It appears in the mirror each morning, toothbrush in hand.” Now Shteyngart is 41, and he’s written three novels and a memoir, all of which wrestle with his past, his parents, his place. It would seem the all-familiar subject is still standing in his mirror, perhaps with a bit less hair. And it isn’t going away soon. This is the tenacity of memoir as an act, as an art as precise and painstaking and ultimately blind as bonsai or marriage. This is why writers say that the craft is an art of revision. The evidence is abundant in Little Failure.

The author begins by revising his identity: He was born Igor, but his parents struck this when they found out about Frankenstein; much later in life, he finds that while “Shteyngart” is a corruption of Steingarten, or Stone Garden, even this came from the slip of some Soviet pen—his real family name was Steinhorn, or Stone Horn, making Gary “Igor Stone Horn.” This prompts a weighty realization for the author: “I have clearly spent thirty-nine years unaware that my real destiny was to go through life as a Bavarian porn star.”

Shteyngart continues this tailoring, hedging, and revising throughout the memoir as he struggles to find not only the right words but the right narrative:

When I walked into the Sheep Meadow in Central Park after my first day of Stuyvesant, I thought a part of me broke. A connection to the past. A straight shot from Uncle Aaron’s labor camps and the bombs of the Messerschmitts to the wield of my father’s hand and the lash of my mother’s tongue to the boy who writes “Gary Shteyngart” and “SSSQ” on his Hebrew school assignments.

But Shteyngart hedges, revises: “Maybe the connection didn’t break,” he writes. “Maybe is just bent.”

Little Failure isn’t Shteyngart’s definitive life narrative. If anything, the memoir establishes him as a half-sifted collection of memories earned and inherited gravitating toward a hot center, a force of will bent toward self-exploration and -definition. “But I don’t want to end my Oberlin story there,” Shteyngart will say, or “Allow me to backtrack to sophomore year” (after, by the way, he’s “ended” his Oberlin story—twice).

The act of memoir is not necessarily written. The process of selection, omission, and revision is one in which we engage every day, waking, sleeping, and daydreaming. Memoir can even pick up where memory fails. Shteyngart’s written memoir is an engaging seminar on the lifelong task. It illustrates, among other things, that identity is fluid enough for one person’s “memoir” to flow into another’s. The bulk of Little Failure grapples with Shteyngart’s parents: the parents who had not read his latest novel, but were quick to share blog posts saying Shteyngart would be forgotten. The mother who labeled potential playmates as “disease carriers,” but later taught her son to smoke cigarettes without inhaling, as a calculated concession to peer pressure. The father who calls him Mudak (or “testicles”) after hearing that the parents in The Russian Debutante’s Handbook slightly resemble himself and his wife, but who says in an aside, “You know, little son, you could write an entire book about me.”

These are the contradictory lives and personalities that flow into Shteyngart’s contradictory life and personality. What he’s done with them is impressive. The effort of Little Failure is titanic, the execution masterful, and the result unsettling, in the best sense of the word. And the photo captions alone are worth the sticker price. The book’s scope, though, might be the most impressive measure—and Gary lets us know as only he can. “I consider in great detail the nothingness to which we will all eventually succumb,” he writes, “and its very opposite, the backside of Tahnee Welch partly shrouded in a pair of white summer shorts.”

Little Failure is just such a titillating mess of contradictions.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v13n4 (Week of Thursday, January 23) > Lit City > Book Review - Little Failure: A Memoir This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue