Almost Holy

by Jordan Canahai

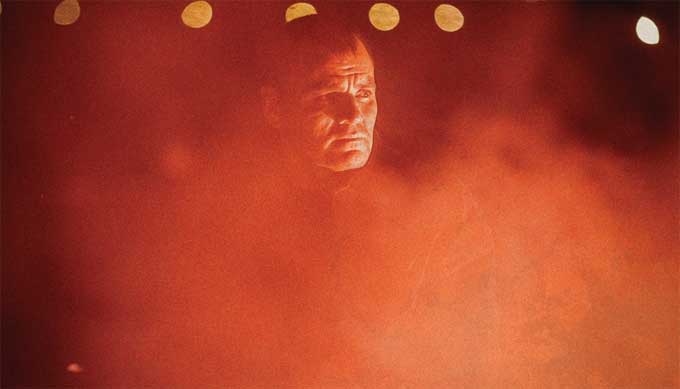

The vigilante hero is a popular archetype in modern cinema, reflected in characters as varied Travis Bickle and Batman. Steve Hoover’s fascinating documentary Almost Holy profiles a totally unconventional real-life vigilante. The film’s subject is Gennadiy Mokhnenko, a Ukrainian pastor who employs controversial methods to help drug addicted youths escape lives of poverty and crime. Along with running the Pilgrim Republic rehab facility, Mokhnenko operates outside the law, carrying out nighttime raids in the worst neighborhoods to get kids off the streets and into his treatment program. As one would expect from a vigilante pastor, Mokhnenko proves to be a subject full of contradictions. He’s both selfless and self-righteous, possessing an intense charisma that makes him a compelling protagonist.

The film alternates between material recently filmed as well as archival footage captured throughout various moments during Mokhneko’s public life. Hoover doesn’t shy away from addressing harsh criticisms of his subject, who has been condemned by his fellow Ukrainians as frequently as he’s been praised. Some argue his facility provides the city of Mariupol a much needed public service while others believe he should face criminal charges. Mokhneko is a man who craves the spotlight and whose deeply held convictions, fueled with a zealous fervor, can make him difficult to work with. For Mokhenko, placing himself above the law is justified when given the opportunity to save a youth from addiction. Hoover’s direction is marked by a keen intelligence; he captures his subject’s actions objectively and trusts in his audience to question them accordingly, coming to their own conclusions about the man. In some scenes his approach recalls the manner Frederick Wiseman examines social institutions, most recently as he did in last year’s essential In Jackson Heights.

The heart wrenching stories of the drug addicted children, explored sporadically throughout the narrative of Almost Holy, will prove difficult viewing for some. Many of the kids are young enough to be in elementary school. The film’s most painful scenes concern the failed rescue attempts of broken lives that, despite Mokhneko’s best efforts, prove beyond his abilities to save. Despite the shroud of quiet despair that emanates throughout, there are also moments of uplift and good-natured humor contained alongside the darkness. Mokhneko is shown to be a caring father-figure and teacher to the children he looks after, while his loving wife has always worked hard alongside him to assist in the duties.

Hoover doesn’t allow the specifics of rehab therapy or the particulars of the kid’s sufferings to bog down Almost Holy during its concise 94 minute runtime, but it’s clear as a filmmaker he feels the same empathy for their plight that Mokhneko does. Cinematographer John Pope’s compositions capture the film’s action with startling intimacy while always conveying a sense of the larger industrial setting, transforming the decaying urban spaces into what feels like another character. With its visual power, haunting score, and moments of deep human feeling, it’s understandable why executive producer Terrence Malick was drawn to Hoover’s vision. Almost Holy opens with the quote from Isaac Babel “a well thought out story doesn’t need to resemble real life. Life itself tries with all its might to resemble a well crafted story.” In giving audiences a glimpse into Mokhneko’s real life story, Hoover’s documentary asks audiences to act on our empathy for those less fortunate and make a difference. Almost Holy succeeds both as a strong character study and a harrowing social document. A free screening will be presented by the Cultivate Cinema Circle and Squeaky Wheel at Burning Books this Wednesday at 7pm.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v15n07 (Week of Thursday, February 18) > Almost Holy This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue