Next story: Free Will Astrology

Power Failure

by Geoff Kelly

In the introduction to her book Power Failure: Politics, Patronage and the Economic Future of Buffalo, New York, released this week by Amherst-based Prometheus Books, author Diana Dillaway notes that those who hold political and economic power—and who are in a position to lead by virtue of that power—are not always willing or able to provide leadership.

“In fact,” she writes, “Buffalo’s business, political and community leaders—with some rare but interesting exceptions—were zealous in their defense of the status quo in the face of an economic slowdown, and, later, spiraling decline.”

Power Failure offers a series of case studies in Buffalo’s failures of leadership and missed opportunities over the past half century. The decisions that Dillaway chooses to profile represent a Wailing Wall of Buffalo’s past miscues: locating UB’s new campus in Amherst instead of downtown; hemming and hawing on the rapid transit system; turning away the possibility of a downtown football stadium; thumb-twiddling on waterfront development; failing to engage the city’s African-American community in decision-making processes, such as they were; refusing to face the decline in the city’s heavy industrial base, and the consequences of that decline, until it was far too late.

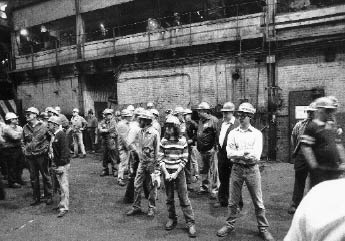

The power failures that Dillaway’s book describes are failures of initiative and vision which she attributes to fear of change in the city’s power structures. But change, she notes, was inevitable:

“Both the economic decline in the 1960s and the loss of the steel industry through the 1970s represent a crisis that brought unimaginable change to Buffalo,” Dillaway writes. “The irony here is readily apparent. Major change—the very thing Buffalo’s leadership hoped to avoid—came, in part, as a result of the leadership’s unwillingness to risk change.”

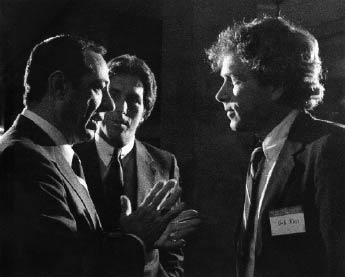

Although politicians make easy marks, Dillaway’s studies place the lion’s share of the blame for these failures with the power elite—the city’s oldest and wealthiest families, the heads of banks and influential law firms and insurance companies, those who sit on boards of directors for various companies—whose money and control of the city’s institutions have always lent their decisions (or lack of decisions) special weight.

About the author

In this, Dillaway is indicting her own class. Though she has resided in California for the past 30 years, she is a member of Buffalo’s Wendt family. Born here in 1941, Dillaway spent her first five years in Derby, until her family moved into the city, living first on West Ferry and then on Argyle Park.

Like many children in her family’s social circle, she attended the Elmwood-Franklin School until eighth grade. Then, rather than follow the typical path—the Buffalo Seminary for girls, the Nichols School for boys—she went away to Miss Hall’s School for girls in Pittsfield, Massachussetts.

After a year of finishing school, she returned to Buffalo, married and had two sons. She lived in Buffalo for the next 15 years, a firsthand witness to the decline which she chronicles in Power Failure.

“All those years it was clear that so many businesses were leaving town, and it just amazed me that all the powers that were couldn’t come together on a vision or plan,” Dillaway said in a recent interview with Artvoice. “I don’t think I was in any position to figure out how or why they could do it. But the lack of a vision or a plan among the business and political leadership was evident to me then.”

In 1974 she drove cross-country with her two sons and her second husband to California, where she worked for the San Francisco Symphony and later for Mother Jones magazine. Eventually she became involved with nonprofit organizations in the Bay Area that had regional concerns. As a result, she was invited to speak at a roundtable on regional planning at UCLA, a sort of accidental expert.

“I really didn’t know what I was talking about,” she admits. “I mean, I had written a great proposal. But that’s all.”

So, in her mid-40s, Dillaway applied and was accepted to the University of California at Berkeley to study urban planning. There she studied with sociologist and urban planner Manuel Castells, whose work would inspire the research methodology for Power Failure. She laid the groundwork for the book while at Berkeley, too, in a statistical comparative study of Buffalo and Pittsburgh and their industrial declines. In fact, at one point Power Failure was to have been a comparative history of the two cities; in the end, however, Dillaway chose to focus on Buffalo alone.

She did her first round of interviews with 35 business and political leaders in 1987. She picked up her research again nearly 10 years later, in 1996, adding another 35 interviews. She promised anonymity to everyone she spoke with—an interesting consideration, given that so many of the decisions she talks about are done deals, and the people who remember how and why they were made are somewhat removed from their former positions of influence.

Asked why she made that promise, she laughed: “Do you think I would have gotten that story if I’d said I was going to use names?”

In fact, she said, her interviewees still feel that they have much at stake—and that is illustrative of the problem she chronicles in the book.

“You know, the social community—and it doesn’t matter if it’s the political community or the establishment—they protect their own,” she said. “One can argue, as I do in the book, that this leads to protection of the status quo, because no one is going to call someone on something. They are going to see each other at the social club tomorrow, or they’re going to see each other at the next Democratic Party gathering, or whatever, and they’re not going to call each other to task.

“I think what people are always afraid of is that it’s going to be a muckraking piece. And this for me is a very serious attempt to get the story and to tell it. Not to make it sensational. And you know, of the 70 people, there were only three who wouldn’t be interviewed. But the reason they didn’t want to be is, they said, ‘Look we don’t want our dirty linen out there.’ Of course, I feel that’s been part of the problem—an unwillingness to look deeply at what’s been going on, and to name it.”

Which, of course, is precisely what Dillaway has set out to do. Reading Power Failure is a head-shaking experience—a painful reminder for the civic-minded of what might have been.

How UB ended up in Amherst

“The biggest [missed opportunity] would be the university,” Dillaway said, of the debate over whether to build a new campus for SUNY at Buffalo on the waterfront downtown or on a suburban site.

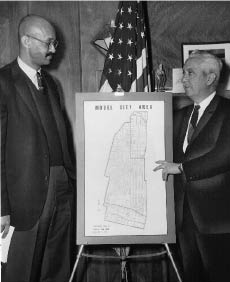

In 1962 Governor Nelson D. Rockefeller had announced that SUNY would build a second, larger campus for UB. Though he never committed fully to any one location, Rockefeller seemed to suggest that he favored a downtown campus.

“This was the greatest opportunity handed to [the city’s business and political leaders],” Dillaway said. “Not only did the governor propose that this could be a possibility, but you had all the available urban renewal funds that could have helped with the development downtown around the new campus.”

The city’s small business owners backed a downtown campus, as did the city’s African-American community, whose leadership recognized that the proximity of a waterfront campus to the city’s East Side would mean job opportunities for blacks and much-needed investment in the surrounding neighborhoods, which were already feeling the consequences of the shrinking industrial base and the loss of high-paying jobs.

But, according to one of her anonymous interviewees, downtown interests “turned their back on the university…they fought Rockefeller. And partly they resisted because they saw it as a threat. If there’s two or three billion dollars of stuff going on [either downtown or out there]…it was going to become the power center, and it was going to bring in new people and new money, and overwhelm them.”

Buffalo’s Chamber of Commerce and the Greater Buffalo Development Foundation took no formal positions on the issue—not surprising, Dillaway suggests, except that a downtown campus was so clearly a boon for a city that had been on the decline for 50 years already. A new campus meant, among other things, 10,000 students in the city’s downtown core; 2,000 university-related jobs; in-fill development in city neighborhoods to handle the university’s housing needs; an addition to the city’s already rich cultural life; and research centers that might spawn new businesses that would diversify the city’s flagging economy.

Just as important, Dillaway points out, a downtown campus would have provided the city’s business and political communities with access to tremendous planning resources that might have helped them to steer the city through the changes that attended the death of the region’s heavy industry.

“The big thing about the university for me is, not only does it help the ecomony, it also helps the business and political leaders, because you have such incredible resources and expertise,” she said. “I remember at Berkeley doing all kinds of studies and plans for different outlying areas in the Bay Area—and then we would turn them over to the city government and say, ‘Here’s your plan.’

“Why give the money to some consulting firm when you can get [plans and studies] for free, from the best minds going, with the most up-to-date analysis tools?”

The very thing that doomed the downtown campus, according to Dillaway’s anonymous interviewee—that the university’s enormous economic and politcal presence would disrupt the existing power structure—also might have provided cover for politicians and community leaders who hoped to buck the status quo and embrace radical changes to manage or even reverse the city’s decline.

Instead, the supporters of a downtown campus where marginalized. This was possible, according to Dillaway, because the organizations that should have been driving the planning process and championing the city—the Chamber of Commerce and the Greater Buffalo Development Foundation—instead sat out the debate, most likely due to pressure from powerful interests opposed to a downtown campus. In the absence of a cohesive, empowered and proactive organization, individuals opposed to a downtown campus were able to hijack the debate—and those in favor were left on the periphery, with no recognized, established organization through which to agitate for their cause.

“The structure of power and the planning process directly impact the political and economic outcomes,” Dillaway said. “The Greater Buffalo Development Foundation, which was the seat of power supposedly, did not include a couple of the major players. They might have been a part of it in name, but from what I saw they were not party to a lot of decisions and what the Greater Buffalo Development Foundation did. And when not all of the parties are brought to the table, then it allows those few individuals to impact from the outside the decisions that might have been made.”

The city’s mayor, Chester Kowal, made little effort to win the campus for the waterfront. The Buffalo Evening News played down the issue. The Courier-Express covered the issue thoroughly but did not endorse one site over another.

The tone of the debate was, at times, quite heated. Dillaway writes:

During the increasingly rancorous debate, a banker, who also chaired the Albright-Knox Art Gallery board, blocked the display of a model of the proposed downtown university at the Gallery. It was displayed instead at the Buffalo Public Library at the base of the main stairwell. “As a consequence, the rest of the political and social establishment was cowed into silence…The unanswered insult sent a strong message to anyone who might harbor modern ideas for Buffalo.” Another banker made his feelings known to anyone who would listen, but most especially among the the social networks of the establishment: “We don’t want all those [New York radicals and people of color] running around downtown.” As fate would have it, both leaders sat on the University’s Board of Trustees—one headed the Board and the other chaired the Construction Fund.

How the football stadium went to Orchard Park and the LRRT went nowhere

“Leadership,” Dillaway writes, “requires the commitment to see a project through.”

Buffalo’s light-rail transit system, which took more than 20 years to be planned and built, is another example of a decentralized planning process hung up on the rocks of indecision, indifference and individual agendas. Slow and creaking from the start, the planning for the LRRT gained almost no local support among the power elite—no local dollars were committed to its construction—and as a result the plans were modified in ways that compromised its original intent. The downtown part of the LRRT was supposed to be underground; the suburban part, which was to extend all the way to UB’s Amherst campus, was to travel aboveground.

“That whole point was to have an underrgound line downtown that would bring people downtown for shopping, and in inclement weather they could get around,” Dillaway said. “Or people from businesses downtown could go from one business to another, hop the line and go two stops and go to a business appointment in a snowstorm.”

Dillaway says that one major proponent of the LLRT, an associate of the board members of the Greater Buffalo Development Foundation, told her that if that body had taken a stand when the transit sytem was being challenged out in the neighborhoods—where neighborhood leaders were fighting, with good reason, the overhead rail going through their living rooms—if the foundation had taken a strong stand and then bargained with the community leaders, a deal might have been struck. And Buffalo might have had a more reasonable light-rail system that extended all the way to the northern suburbs, that would not have left Main Street closed to automobile traffic—and it would not have taken 20 years.

The story of the football stadium is appalling. In 1964 a report determined that the best place for a new football stadium would be in or near the urban core. Three years later, Buffalo’s Chamber of Commerce issued a report suggesting that a two-stadium complex be built in Amherst instead. In this fight, nearly everyone took a side, Dillaway writes, and for a variety of reasons. But the basic reason for opposition to a downtown stadium was that a handful of people in the city’s business elite stood to make more money on the construction of a stadium in the suburbs.

Of this debate, Dillaway writes:

…when one bank executive looked like he might agree that a stadium should be built downtown, “he went into his board meeting, and came out a changed man,” and was not heard to assert himself on the stadium issue again. Implicit among the business leadership was the understanding that “if you [want to] build it downtown, you will be destroyed,” according to one longtime political insider. “The battle raged from the summer of ’68 over a plan to build a domed stadium in Lancaster, New York. The proposal fell apart in 1970…[It was] a massive, searing debate involving every major power figure in Buffalo ranging from the owner of the dominant newspaper, bankers, local governments, politicians, editors, law firms…Two people died of heart attacks, politicians quit, two went to prison. The proposal fell apart in 1970.”

In the end, the city’s leaders, realizing that they could not settle the issue for themselves, threw the decision to the New York State Urban Development Corporation. The UDC, more concerned with economic factors than with revitalizing the city, choose the current site of Rich Stadium in Orchard Park. Ten years later the State Supreme Court ruled that Erie County had breached its contract with the developer of the proposed Lancaster stadium.

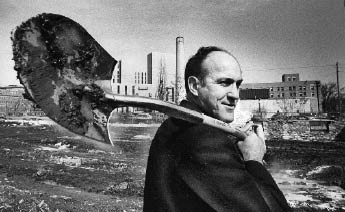

The transactions of decline

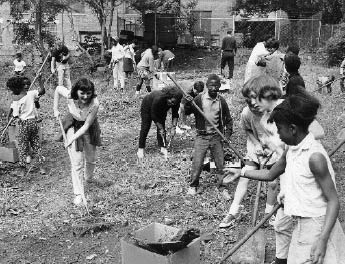

Power Failure traces these stories and the city’s institutions through three decades of decline. One of the most interesting threads include the Democratic Party’s habit of alternating ethnic groups in leadership positions, in order to keep its constituents happy. This excluded the African-American community, of course, whose only outlet for representation was the Common Council. This is a shame, according to Dillaway, because Buffalo’s black leadership in the 1950s was amenable to cooperating with city leaders on urban renewal. Buffalo’s solid black middle class, built on high-wage jobs in the steel and other heavy industries, comprised a very civil society, committed to bettering its lot through existing institutions. Dillaway notes that when Chicago organizer Saul Alinsky—never a friend to existing institutions—visited Buffalo in 1966, he wrote, “I keep sort of rubbing my eyes from time to time. Buffalo is about the only community in America in which I have seen a certain number of middle-class professional Negroes committed to their people.”

But real change never stood a chance in Buffalo, Dillaway says, until the 1980s, when new investment began to come into the city, attracted by subsidies. The new investors demanded, and received, a seat at the decision-making table.

“Around 1975, when things did hit rock bottom and the city was days away from bankruptcy, it was that period when new investment came in, private investment, and that was because of the low cost of capital, through all the subsidies—low cost of capital, the low cost of land,” Dillaway explains. “And labor had taken such a hit, too—they realized that they were a part of the problem, and they backed off some of the high wages and they even tried to help. That’s when the new investors came along, and that wouldn’t have happened if the city hadn’t come to the bottom. I find it difficult sometimes to say that something is good or something is bad, because sometimes something that looks bad turns out to be good. It’s just the catalyst you need.

“During the Griffin years, downtown they did accomplish quite a bit, but it was all with subsidized funds and very little private investment—and then, of course, when the money ran out everybody disappeared.

“These are transactions of decline, as Jane Jacobs says, and once they are going it’s hard to get off of them. On the one hand, you had Griffin setting up all these nonprofits to take funds and actually getting- things done, and that was the good side. The bad side was the acrimony [caused by] the process that left out his Council—which has really affected the city for decades afterward. It set up a dynamic that I don’t know is even over.”

The failure to embrace change, Dillaway says, is certainly a negative, too. But it says something positive about the city as well.

“You had the ethnic communities not wanting change at all, because their lives were settled and quite wonderful, in the sense that everything revolved around the parish church—and then, of course, the Democratic Party machine, patronage. The schools were right there, and the parish priest was right there. They didn’t want change. And the establishment didn’t want change, because life was very, very good for all of us. The black community, of course, wanted change, and for good reason.

“The one thing it does say for the city is that it is a wonderful, wonderful place to live. The thing is that, unless a city is willing to risk change, they are going to be forced by circumstances into change, because change is inevitable.”

Photos courtesy of the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society.

To respond to this article send an e-mail to editorial@artvoice.com or write 810 Main st. Buffalo, NY 14202.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n17: Power Failure (4/27/06) > Power Failure This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue