Next story: Free Will Astrology

Open for Business, Fighting for Choice

by Geoff Kelly

In the months that followed the appointments of first John G. Roberts and then Samuel A. Alito, Jr. to the US Supreme Court last fall, the matter of abortion rights returned to its familiar place as a centerpiece of national debate—a place the issue occupies whenever a new justice is nominated to the court and in the runup to every national election. In the 33 years since Roe v. Wade allowed for the possibility of safe, legal abortions throughout the US, politicians and judicial nominees at every level of government have been pressured to stake out clear positions on the ethics of abortion and a woman’s right to choose.

The fight over abortion rights takes place quietly and continually in legislatures and courtrooms, and often loudly in street-level protests. It also manifests violently on the fringes of society, where anti-abortion extremists plot to destroy clinics and—as residents of Western New York know as well as anyone in the nation—to murder doctors who perform the procedure.

Paradoxically, abortions themselves, and the doctors and clinics who provide them, share a blind spot in the American consciousness, according to Dr. Katharine Morrison of Buffalo GYN Womenservices, one of a handful of abortion providers in this region. Abortion is, according to the most reliable statistics, a commonplace. Rates are declining, in large part due to the increased availability of contraceptives, but there arenonetheless nearly two million abortions per year in the US, according to the Guttmacher Institute. Forty-three percent of American women have had an abortion by the age of 45.

In other words, virtually everyone knows someone who has had an abortion. Everyone knows someone for whom terminating a pregnancy seemed a reasonable choice that worked out well. But, in an era when formerly taboo subjects such as rape and sexual abuse are openly discussed on television and in movies and the other avenues of our cultural discourse, almost no one talks about having had an abortion.

“I think one reason that those who oppose abortion have been able to get us to this juncture is that abortion has been so very successful,” Morrison says. “First of all, you don’t know anyone who had an illegal abortion and suffered because of it. I’m going to be 50 this year, and I had a friend who died as a result of an illegal abortion that she had when she was 16. But people who are 30 don’t know anyone to whom that happened.

“The people who fought for abortion rights remember what the alternative is: You couldn’t get an abortion; or you had to have an illegal, unsafe abortion; or you had to go before a hospital board and plead your case and let the board decide if you were a worthy case for a termination.

“And it’s never portrayed anyplace. Anything goes on TV now—but somebody gets pregnant on TV or in the movies and they either choose to continue the pregnancy, and everything works out just great, or they have a miscarriage, and it’s unfortunate, but the pregnancy ends without anyone having to terminate it.

“People will say, ‘Well I had my appendix out,’ or ‘I had a hysterectomy,’ or ‘I was raped.’ All those other things people will talk about now. But no one can say, ‘I had an abortion and it worked out fine.’ Because abortion has been so very successful, it has also been below the radar.”

The hazards of the profession

For much of her 22-year career as a physician, Morrison, too, has tried to operate below the radar.

Morrison graduated from the University at Buffalo’s School of Medicine in 1984, then moved to New York City to do an obstetrics and gynecology fellowship. She returned to Buffalo in 1988 and worked for Healthcare Plan until 1998, then began splitting time between Buffalo and Bath, New York.

She began working at Womenservices in July 1998, just three months before Dr. Barnett Slepian, the clinic’s principal physician, was shot to death in his Amherst home by sniper James Kopp, an anti-abortion activist. She gave up her job in Bath in 2000 and has been with Womenservices ever since, with occasional work in New York City.

After Slepian’s murder, Morrison, DuBois and all the clinic’s employees became far more conscientious of the danger that attended their profession. Morrison continued to work at Womenservices, but quietly, telling people around town that she had left the clinic. But eventually, she says, people found out she was still there and still performing abortions. When they did she left the city, because she didn’t think it was safe for her family.

Last November, Morrison and clinic director Melinda DuBois purchased Womenservices from its long-time owners; for several years the partners effectively had been managing the clinic.

DuBois and many other employees don’t use their married names, to make it more difficult for anti-abortion activists to find their homes and so their children will not be harassed in school. They are all careful to whom they talk about their jobs.

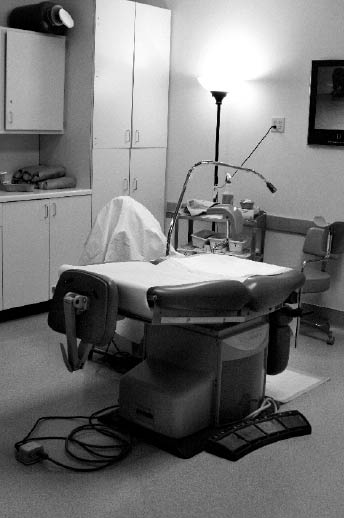

The clinic uses armed guards, 24-hour video cameras and a security system. In order to be buzzed in, visitors must have an appointment and state their names into an intercom; all visitors must produce identification; no backpacks are allowed and the guards will sometimes search patients to be sure they’re not bringing anything dangerous into the clinic. Staff meetings include bomb and fire drills. On more than one occasion anti-abortion protestors have managed to burst into the clinic and harass the patients and employees, clinging to furniture and doors when guards and police tried to drag them away.

When the anti-abortion group Operation Rescue brought its massive street-level demonstrations to Buffalo in 1992, at the invitation of Mayor Jimmy Griffin, throngs of anti-abortion protestors surrounded patients as they made their way into the clinic through the front door facing Main Street; the patients were, in turn, protected by throngs of pro-choice escorts, who turned out in tremendous numbers—far greater numbers than Operation Rescue and its founder, Randall Terry, had expected. Operation Rescue’s efforts in Buffalo were, to some degree, the death knell for an already dying manifestation of the anti-abortion movement. Though Terry and his followers had enjoyed great success—and a great deal of national publicity—shutting down clinics in Wichita, Kansas, the year before, Buffalo was a dismal failure. In Wichita, the protestors had enjoyed the support of sympathetic politicians and judges. In Buffalo their only ally was Griffin, whose hugely unpopular invitation to outside agitators resulted in unwelcome chaos on the streets. Local judges such as Richard Arcara and John Curtin held a hard line with the anti-abortionists; Arcara’s rulings led to the Freedom of Access to Clinics Entrances Act (FACE), which allowed patients entering a clinic a 15-foot buffer zone that followed them as they moved, and into which protestors could not intrude under penalty of arrest. After eight days and nearly 700 arrests, Operation Rescue packed its bags and left town.

“FACE really saved us,” says Morrison.

In the next few years numerous lawsuits brought against Operation Rescue, most notably by the National Organization of Women but by other pro-choice organizations as well, crippled Terry’s group. In November 1998 Operation Rescue declared bankruptcy, claiming $1.7 million in debts, $1.6 million of that owed to NOW.

In the years that followed, clinic protests—though they persist—lost much of their popularity among the anti-abortion movement, which turned instead to courts and legislatures to whittle away at access to safe, legal abortions. The radicalizing effect of street-level protest, however, encouraged extremists in the anti-abortion movement to violence. In the 1980s and 1990s, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, anti-abortion activists were responsible for six murders, 15 attempted murders, 200 bombings and arsons and 72 attempted arsons. Two clinics were fire-bombed in Florida just last year. And threats of violence are a weekly occurrence.

So far Slepian’s murder is the starkest act of violence that has attached to the clinic, though two years ago a man was arrested with a houseful of guns and a list of names that included DuBois and Morrison. Authorities notified the clinic of the arrest and the circumstances.

“Luckily for Melinda and me, he also threatened a sheriff and a judge,” Morrison says. “You go to jail for a while when you threaten a sheriff, and a judge. We were also very lucky because he wrote his sister about what he was going to do and she notified the police. There were guns and drugs in the house, too.”

“And you just don’t know who else is out there wanting to try something just like that,” DuBois adds. “A lot of people think that because there are not so many protestors, or they haven’t seen them in the news, theings have quieted down. But I think that’s false. Certainly things have heated up in the political arena.”

Nowadays patients park in a rear lot and enter the clinic through a door there, so only those who take the bus are subject to verbal harassment. The use of racketeering laws to prosecute protestors and the FACE Act have been challenged in recent years—the buffer zone is likely to be rolled back to an area surrounding the clinic rather than the patient—but the number of protestors at Womenservices has dwindled to a handful of picketers standing across the street from the clinic day after day, week after week.

On the surface it seems that the debate has become kinder and gentler. But Morrison and DuBois don’t feel any more secure today than they did in the years leading up to Slepian’s murder. The public may read about the abortion war only during elections and the vetting of Supreme Court nominees, but the partners are acutely aware of a multitude of threats to themselves and a woman’s right to choose.

“I don’t think that the atmosphere for a clinic like ours has changed at all,” DuBois says. “The protestors haven’t changed. The same people, the same stories, the same rhetoric, the same issues, the same signs. There are a couple of new protestors who come and rile everyone up. But mostly it hasn’t changed.”

Expanding services

Since taking over the clinic, Morrison and DuBois have embarked on a plan to expand the services the clinic offers. They aim to provide a continuum of ob-gyn care for women—especially for women who, for one reason or another, are reluctant to seek medical care.

“We’ve always been known as the abortion clinic, and that is still what we do,” DuBois says. Womenservices now does abortions up until 22 weeks for patients whose pregnancies show signs of birth defect or other anomalies; previously the clinic, like other abortion providers in the city, set the limit at 20 weeks. Until now patients who needed an abortion later in their terms were referred to clinics in New York City. The legal limit for abortions in New York State is 24 weeks.

Womenservices is also expanding its gynecological practice, in part because many of Morrison’s former patients would like to return to her care. The partners also hope to reach out to the lesbian community, a population that frequently avoids medical care for a variety of reasons.

“Mostly with lesbian, bisexual and transgendered population, it’s mostly a fear of going to the doctor, especially for a very intimate exam—fear of being ridiculed or not being treated with respect or of being treated roughly,” Morrison says. “What women in that situation need is to know that they are going to a gynecologist in a setting where they will be treated with respect and where their sexuality is not an issue. It’s a note for your medical record, but it does not mean you will be treated differently.”

Morrison and DuBois also believe that many of the patients who come in to terminate pregnancies would prefer to stick with Womenservices for gynecological care.

“Because we spend a lot of time with our patients, and because we have counselors who talk to our patients, they become comfortable with us and would prefer to come back here for their gyn care—as opposed to seeing a doctor who they don’t know, who they don’t know anything about, who may see them for a very short period of time. Sometimes they don’t want to see their regular doctors again if they think they’re going to be judged.”

Fear of judgment is a big factor for women who seek to terminate a pregnancy, regardless of the reason.

According to Morrison, some of her patients say that their doctors have told them not to come back if they choose to terminate a pregnancy. More often, she says, they just don’t want their doctors to know. “They’ll say, ‘You can’t tell him, because if you do I won’t be able to go back there.’

“As a physician myself I am often shocked at what patients will tell me other doctors have said to them. And often I’ll say to myself, ‘Oh no, he couldn’t have said that, you must have misunderstood.’ But then I’ll hear from a nurse or somebody else in his office, ‘Oh no, he does say that.’”

“Unfortunately I think many women hide a lot of issues from their gyn, who is the one person they should be telling everything,” DuBois says. “But they fear that judgment.”

“And it works against women’s interests,” Morrison adds, “because that’s why so many doctors think their patients don’t get abortions. You know, so many gynecologists that I know think that the population I see is radically different from the population that they see. They don’t understand that they are the same patients.”

Just as abortion and those who choose it are stigmatized, the clinic and the people who work there are stigmatized as well. Morrison recalls attending a conference at Children’s Hospital and being asked where she worked by one of the administrators there.

“I told him I worked at the abortion clinic on Main Street. And he looked at me and said, ‘Oh, you shouldn’t say that.’ I asked him why not, and he said, ‘Well, I’m sure you’re not just doing abortions.’ And I said, ‘No really—that’s what we’re doing.’

“They consider it so shameful and so beneath what a real doctor would do that he didn’t want me to say that’s all we did.”

Because the clinic is marginalized, in some sense, by the community and the medical profession, their patients feel more comfortable—and able to discuss health matters that other physicians can’t or don’t discuss. Womenservices takes Medicaid, too, which opens their doors to many patients who have no other options.

Some doctors will refuse to provide medical information about their patients who go to Womenservices for an abortion. Women who receive care through the Catholic health system sometimes are restricted in their access to contraception, and are therefore more prone to unwanted pregnancies. Until recently, Sisters Hospital refused to fax the clinic sonograms the hospital performed for patients whom Morrison suspected had ectopic or extrauterine pregnancies.

“We would have to explain to them, ‘You don’t own that information. That’s the patients information.’ It finally hit them about a year ago. They finally got it,” Morrison says.

DuBois sits on the board of Crisis Services, which helps victims of rape and assault, and Womenservices often treats patients who are pregnant as a result of rape. The clinic works with police in order to provide them DNA evidence. “We’ve also been talking about becoming a referral for patients who have been sexually abused or raped and have a hard time going to a gyn after that—and there are a lot of women who have that issue. And again they avoid care, they just aren’t being seen, because they can’t handle it.”

Womenservices currently provides training in abortion procedures for doctors from all over the country. The UB School of Medicine’s Family Practice Department is particularly eager to have its students train to perform abortions. Those students can come for a week or a month or however long they’d like, Morrison says. There are stipends available and the students can choose what procedures they wish to learn—e.g. first trimester abortions, second trimester abortions.

UB’s Ob-Gyn Department, on the other hand, won’t even allow Morrison to come to speak to their students.

“There was one resident there who wanted to come to the clinic and the department said he could not,” DuBois says. “They told him that if he did, they would not cover his malpractice insurance.

“It wasn’t just that they wouldn’t let him do a rotation here,” Morrison said. “They wouldn’t permit him visit the clinic on his off days.”

The future of choice in Buffalo

In any case, DuBois says, none of the residents that Womenservices trains stay in Buffalo, open up reproductive health clinics and offer abortions. They all leave. There are a few doctors in private practice who still offer abortions, most notably Dr. Shalom Press, whose son Eyal recently wrote Absolute Convictions: My Father, a City, and the Conflict that Divided America, a unique narrative of the events that made Buffalo a hotbed of the abortion debate in the 1990s. The book culminates with the death of Slepian, who was a colleague of Press. The book’s release is well timed: South Dakota recently banned virtually all abortions, the first of a number of pending state challenges to Roe v. Wade that will eventually land before the increasingly conservative US Supreme Court in the years to come.

New York State remains a mostly friendly place for women’s reproductive issues—though there are 19 bills in the state legislature that seek to curtail access to safe, legal abortions, there are nearly twice as many bills pending to protect a woman’s freedom to choose. If the popular and ardently pro-choice Eliot Spitzer sails into the governor’s mansion, as seems likely, then anti-abortion legislators in Albany will be stymied for four years at least.

But the laws in other states continue to straiten; already Womenservices sees many patients who come from Ohio and Pennsylvania, unwilling or unable to face the more restrictive laws in their home states.

“Way back at the beginning when New York first voted to make abortion legal, there were swarms of people coming here,” DuBois says. “That could happen again.”

Anti-abortion legislators in Congress hope to pass a law that would forbid minors from crossing state lines for an abortion; both the patient and the doctor could go to jail. Clinics would be required to enforce the laws of the patient’s home state—e.g., waiting periods, parental consent, etc.

“For now we enjoy some protections here in New York,” DuBois says. “But who knows if it will last?”

She relates the story of a young woman who navigated a hostile crowd of protestors on her way into the clinic. The woman turned to the protestors and said, “If any one of you can give me $50,000, I’ll have this baby. Because that’s what it’s going to cost to raise it.”

“I just can’t figure out what the other side hopes for if they outlaw abortion,” DuBois says. “I always think, Well, then, what are you going to do? The problem of unwanted pregnancy still exists. What’s the next step?”

“I think it’s a struggle against modernity,” Morrison says, nodding. “The same people who want abortion outlawed also don’t want Darwin taught in schools. They harken back to an era that never existed.”

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n19: Open for Business, Fighting for Choice (5/11/06) > Open for Business, Fighting for Choice This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue