French Leave of His Senses

by George Sax

By the ten-or-twelve minute mark in Emmanuel Carrerè’s film you may feel you’re experiencing another riff borrowed from the old Twilight Zone formula. In fact, for more than half of its less-than-hour-and-a-half length, it could pass for a sleek but serious-minded French rendering of one of those bizarro-world fantasy outings.

Then, it makes a sharp turn, taking leave of both its Parisian setting and its storyline, and becomes a movie animal of a rather different stripe. It deliberately leaves its protagonist, Marc, and probably a lot of the audience, in the lurch.

Marc (Vincent Lindon) is an apparently successful architect, married to an attractive wife who’s employed in the professional/administrator class in some fashion or another—it’s never revealed just how, which is the least of the movie’s mysteries.

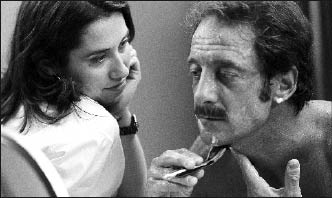

As the film begins, Marc and Agnès (Emmanuelle Devos) are preparing for a party in honor of their goddaughter’s birthday. As he sits in his bath, Marc has an unexpected thought and shares it with his spouse: What would she think if he got rid of his mustache? She doesn’t seem to take the matter seriously, and, on an impulse, he does just that, and awaits her reaction.

But there is none. None at all. Nor do either the man and woman they visit that evening register any recognition of a difference in his appearance. Not even their little girl seems to notice.

Marc assumes that everyone’s engaged in a conspiratorial joke at his expense, but when he confronts his wife on the way home, she responds with confusion, then irritation, and denies any such thing. Even worse, she denies he ever had a mustache.

And the next morning, the people at his boutique design firm seem to be operating on the same unconscious assumption. And the proprietor of the little café across the street doesn’t seem to notice anything new.

This is quickly becoming maddening—in the more consequential meaning of that word. Marc has prior photographic evidence of his changed appearance, although, curiously, he doesn’t show it to anyone but a complete stranger.

Distressed, unable to go to his office, or do much else, and wondering whether it’s he or Emmanuelle who’s losing a grip on life, he agrees to consult a psychiatrist with her. Before that can happen, Carrerè briefly infuses his film with an evocation of Patrick Hamilton’s ancient menacing melodrama, Gaslight, in which a husband tries to dispose of an inconvenient spouse by convincing her and everyone else that she’s mad. In one suspenseful, adeptly constructed sequence, Carrerè seems to be signaling a similar resolution, but it’s only a very temporary digression. The film returns even more seriously to puzzle-making and then Marc abruptly flees to Hong Kong. This destination may have some obscure metaphorical import for Carrerè, but it mainly seems to offer striking skyline and water vistas as backdrops to Marc’s obsessionally indecisive all-day and overnight ferry rides back and forth across the harbor before he finally musters the mental wherewithal to disembark. (This watery setting seems rather obviously to link up with the shots of dark waters that accompany the opening credits. There’s some real wet signification here.)

There are likely to be two general kinds of reaction to La Moustache (which Carrerè adapted from his own twenty-year-old novel): Engagement with the film’s existential puzzles and tantalizing inconsistencies, or annoyance at what will seem to some to be hollow portents and whimsical mystification. I’m afraid I have to make common cause with the second group.

La Moustache comes off as a cross between Kafka and Sartre, with a bit (excuse me, I mean morceau) of Henry James’ Turn of the Screw, but it only coheres in a superficial stylistic way—and then just barely.

Carrerè may well have been trying to suggest something about the insubstantiality of identity, the fragility of reality and consciousness, but the film is too arbitrarily self-contradictory and glib to make much of an enigmatically thoughtful impact. It does benefit from Lindon and Devos’ fluidly subtle performances, and Carrerè’s adept scene setting. But, in the end, it plays out as a frivolous exercise loosely held together by callow Left-Bank attitudinizing.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n29: Casino Chronicles (7/20/06) > Film Reviews > French Leave of His Senses This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue